Search Results for: %22not even wrong%22

37 C.F.R. § 1.75(e), Jepson claims, and the Administrative Procedure Act

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

First Steps After SAS Institute

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Punishing Prometheus: Part V – The Long Punt and the Improbable Return

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Piercing the Corporate Veil: Corporate Officers Are Liable for Their Own Torts

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Lemley & McKenna on IP Scope

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

The Removal of Section 102(f)’s Inventorship Requirement; the Narrowness of Derivation Proceedings; and the Rise of 101’s Invention Requirement

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Fraud on the Court: Finality and the Ghost of Hazel-Atlas

by Dennis Crouch

The Supreme Court will soon consider whether to hear an important case about fraud on the court (and the USPTO) and the judiciary's obligation to address it. Marco Destin, Inc. v. Levy, Case No. 24-787. The issue now before the Court asks whether it was proper for the lower court to overlook fraud that affects the judicial process itself in favor of finality of judgment. [Marco Destin Petition]

Fraud cases are typically interesting reads, and this one fits the bill. In 1993, L&L Wings entered into a trademark license agreement with Shepard Morrow for the use of the "WINGS" mark in retail store services -- particularly for use on beach merchandise. L&L Wings made only the initial $10,000 royalty payment under the agreement, then defaulted on the remaining payments. Despite losing its rights to the mark, L&L Wings continued using the mark and even began sublicensing it to others, including Marco Destin (Alvin's Island) in 1998.

In 2007 L&L Wings (owned by respondents Shaul Levy and Meir Levy) sued Marco Destin for trademark infringement in the Southern District of New York. According to the cert petition, L&L's attorney Bennett Krasner knew at the time that L&L Wings had no rights to the mark, having personally negotiated the earlier failed licensing deal with Morrow. Yet the complaint omitted any mention of Morrow's ownership or L&L Wings' status as a former licensee.

During that litigation, Krasner allegedly deepened the deception by obtaining a federal trademark registration for "WINGS" through what the petition characterizes as fraudulent representations to the USPTO. The application claimed L&L Wings had been in "continuous high-profile use" of the mark for nearly 30 years and failed to disclose Morrow's prior ownership. After obtaining the registration, Krasner introduced it as evidence in the New York case, leading to summary judgment against Marco Destin and ultimately a $3.5 million settlement.

The fraud only came to light years later through separate litigation in North Carolina between L&L Wings and Beach Mart. There, a jury found that L&L Wings had knowingly made false representations to the USPTO to obtain the WINGS registration. The court canceled the registration and awarded $12.5 million in punitive damages. This verdict drove L&L Wings into bankruptcy.

Armed with evidence of the fraud, Marco Destin sought to vacate the earlier $3.5 million settlement through an independent action authorized under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(d)(3). As suggested above, all of this is part of the L&L Wings bankruptcy proceedings and and so Marco Destin is unlikely to obtain its full recovery even if it wins this case -- instead it will form part of the queue with the other creditors.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Guest Post: Secret Software Sales

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Apple v. Samsung: An Expert but Pro-Patent Jury?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

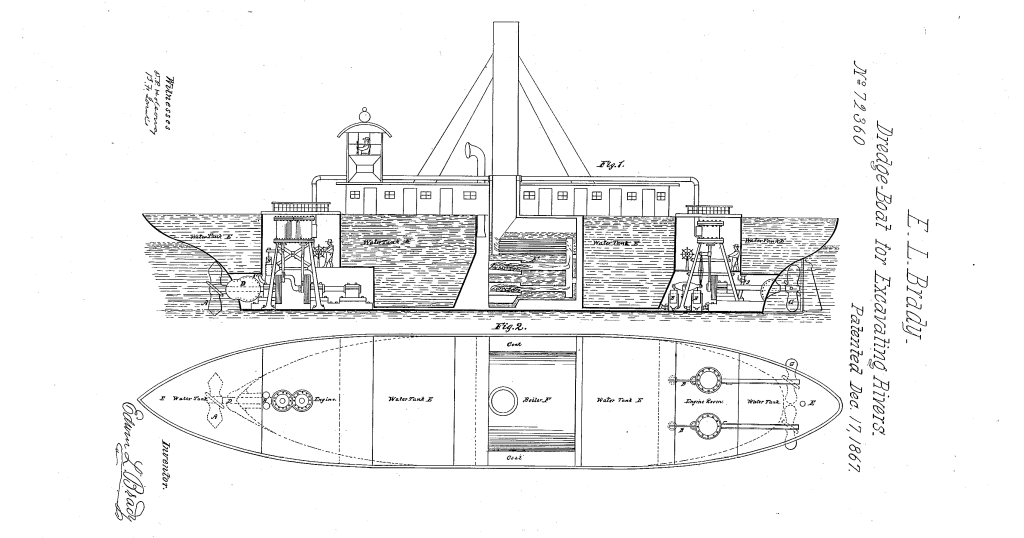

The Quest for a Meaningful Threshold of Invention: Atlantic Works v. Brady (1883)

by Dennis Crouch

My recent discussion of Vanda v. Teva references the landmark Supreme Court case of Atlantic Works v. Brady, 107 U.S. 192 (1883). I thought I would write a more complete discussion of this important historic patent case.

Atlantic Works has had a profound impact on the development of patent law, particularly in shaping the doctrine of obviousness, but more generally providing theoretical frameworks for attacking "bad patents." As discussed below, I believe the case also provides some early insight into the new AI inventorship dilemma.

The case addressed the validity of a patent granted to Edwin L. Brady for an improved dredge boat design. The Supreme Court ultimately reversed the lower court's decision upholding the patent and found instead that Brady's claimed invention lacked novelty and did not constitute a patentable advance over the prior art.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Guest Post by Profs. Masur & Ouellette: Public Use Without the Public Using

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CareDx v. Natera: A Response To Professor Holman

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Oil States: Engaging with History, Private Property, and the Privy Council

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Specification describes machine with sensors – Can you omit the sensor limitation in the claims?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Guest Post: What Ultimately Matters In Deciding the “Gene Patenting” Issue?

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

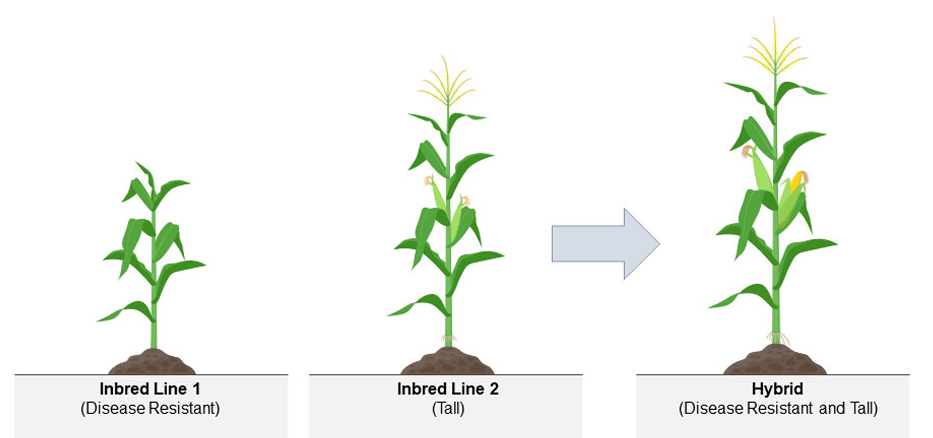

Trade Secrets vs. Patents: Pioneer’s Plant Patent Strategy Raises Thorny Issues (Corny Issues?)

by Dennis Crouch

The ongoing dispute between Inari Agriculture and Pioneer Hi-Bred over utility plant patents has taken its next step, with Inari seeking Director Review of the PTAB's denial of institution in PGR2024-00020 -- arguing that a patentee's reliance on its own trade secret information when developing its invention (here a maize variety) is directly relevant to the question of obviousness. The case raises interesting and fundamental questions about the intersection of trade secrets and patent law in the context of plant breeding. Inari Agriculture, Inc. v. Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Inc., PGR2024-00020, Paper 19 (P.T.A.B. Oct. 24, 2024).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

More Than Just “Inventory”: Some Professional Responsibility Implications of Third Party Patent Assertion Entity Funding

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Mandamus for Improper Venue

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

The Supreme Court to Decide if Trump is Too Small

Guest Post by Samuel F. Ernst[1]

As Dennis reported, the Supreme Court has granted certiorari in the case of Vidal v. Elster to determine if the PTO violated Steve Elster’s First Amendment right to free speech when it declined to federally register his trademark TRUMP TOO SMALL in connection with T-shirts. The PTO had denied registration under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(c), which provides that a mark cannot be registered if it “[c]onsists of or comprises a name, portrait, or signature identifying a particular living individual except by his written consent.” In February, the Federal Circuit held that this provision is unconstitutional as applied to TRUMP TOO SMALL, a mark intended to criticize defeated former president Donald Trump’s failed policies and certain diminutive physical features.[2] The Federal Circuit held that, as applied to marks commenting on a public figure, “section 2(c) involves content-based discrimination that is not justified by either a compelling or substantial government interest.”[3] The question presented before the Supreme Court is “[w]hether the refusal to register a mark under Section 1052(c) violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment when the mark contains criticism of a government official or public figure.”

Under the Supreme Court’s precedent in Matal v. Tam and Iancu v. Brunetti, the Federal Circuit’s decision was almost certainly correct.[4] Unlike the provisions at issue in those cases, which barred the registration of disparaging, immoral, and scandalous marks, section 1052(c) does not discriminate based on the viewpoint expressed; it bars registration of a famous person’s name whether the mark criticizes praises or is neutral about that person. But the provision does discriminate based on content, because it bars registration of marks based on their subject matter. The Supreme Court has held that “a speech regulation targeted at specific subject matter is content based even if it does not discriminate among viewpoints within that subject matter.”[5] Even though viewpoint discrimination “is a more blatant and egregious form of content discrimination,” both viewpoint discrimination and content-based discrimination are subject to strict scrutiny.[6] Even if we view trademarks as purely commercial speech – an issue the Supreme Court has never decided – laws burdening such speech are subject to at least the intermediate scrutiny of Central Hudson, which is the level of scrutiny the Federal Circuit applied in finding section 1052(c) unconstitutional as applied to TRUMP TOO SMALL.

To survive the Central Hudson test, section 1052(c) must advance a substantial government interest and be narrowly tailored to serve that interest.[7] The government argues that the provision advances a government interest in protecting the right of publicity of public figures from having their names used in trademarks without their consent. However, even if the government has a substantial interest in protecting the state right of publicity, the provision is not narrowly tailored to serve that interest. This is because every state’s right of publicity law incorporates some sort of defense to protect First Amendment interests,[8] and “recogniz[es] that the right of publicity cannot shield public figures from criticism.”[9] But the PTO takes no countervailing interests into account before denying registration to a mark under Section 1052(c). The PTO merely inquires into whether “the public would recognize and understand the mark as identifying a particular living individual” and whether the record contains the famous person’s consent to register the mark.[10] Accordingly, section 1052(c) is unconstitutionally overbroad because it burdens speech that the right of publicity would not burden. The provision is therefore far more extensive than necessary to serve the government’s purported interest and is facially unconstitutional.

A peculiar aspect of the Supreme Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence in the context of trademark registration is that a trademark registrant is not only asserting a right to free speech, but also to obtain an exclusionary right to prevent others from using the same speech in commerce (at least to the extent it would cause consumer confusion). In other words, if we are concerned with burdening Elster’s right to proclaim that Trump is too small, it is odd to remedy that concern by giving him a right to prevent others from saying the same thing. Section 1052(c) is not equipped to deal with this larger concern with marks containing political commentary because it only prevents the registration of marks by persons other than the named political figure, and only if they contain the name of that political figure. Outside of this narrow context, the Lanham Act can do great harm to free political speech because it allows for the federal registration of all manner of marks containing pollical commentary. Anyone can register a mark containing political commentary so long as it does not name the political figure without her consent. And politicians are free to register marks making political commentary whether or not they contain their own names. For example, the Trump Organization has a federal registration for the mark MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN.[11] This grant of a federal registration does more harm to free speech than the denial of any registration would, because it allows the trademark holder to prevent others from making the same political comment in commerce to the extent it would result in a likelihood of confusion (or to the extent they are unwilling to incur the expense of defending against a federal lawsuit).

This raises a broader critique of the Supreme Court’s rigid approach to the First Amendment. The Court deals in inflexible categories of scrutiny that focus solely on the rights of the speaker (in these cases, the trademark registrant), without considering how the absolute protection of those rights might affect the speech rights of others. For example, in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, the Court decided that the First Amendment rights of the Boy Scouts were violated by a New Jersey law requiring it to rehire a gay scoutmaster it had fired.[12] But the Court did not consider how the Boy Scouts’ assertion of their First Amendment rights affected the rights of the fired scoutmaster or of other New Jersey employees to publicly express their sexual orientation without fear of being fired. And in Citizens United, the Court vindicated the First Amendment rights of private corporations to support political candidates without considering how the resulting flood of corporate political propaganda could drown out the speech of less powerful private citizens.[13] The trademark registration cases put this issue in stark relief, because in protecting the rights of the trademark registrant to say scandalous, immoral, disparaging, or political things, the Court utterly fails to consider the ways in which the resulting rights of exclusion might prevent other people from saying the very same things. This was the point Justice Breyer made in his Brunetti concurrence, where he argued that “[t]he First Amendment is not the Tax Code.”[14] Rather than focusing on inflexible, outcome-determinative categories, he urged the Court to adopt a balancing test: “I would ask whether the regulation at issue works speech-related harm that is out of proportion to its justifications.”[15] Even under such a test, section 1052(c) would likely not survive, because it is far broader than its purported justification to protect the right of publicity. But such an approach would at least allow the Supreme Court to consider in these trademark registration cases that it is not only protecting a right to speak, but a right to exclude others from speaking.

Several prominent scholars have argued that the PTO could prevent the registration of political commentary marks under the “failure to function” doctrine.[16] The Lanham Act’s definition of a “trademark” requires that a trademark must be “used by a person to identify and distinguish that person’s goods from those of others and to indicate the source of the goods, even if that source is generally unknown.”[17] The argument is that political commentary marks are not perceived by the public as source indicators, but, rather, as political commentary. Under the failure to function doctrine, the PTO has denied registration to EVERYBODY VS RACISM and ONCE A MARINE, ALWAYS A MARINE.[18] Denying registration to political commentary marks under this doctrine might not violate the First Amendment because it is clearly a legitimate trademark policy to regulate interstate commerce. However, this issue is not before the Supreme Court in the Elster case because failure to function was not a basis for the denial of registration of TRUMP TOO SMALL in the PTO. In any event, the constitutionality of section 1052(c) cannot be saved by the failure to function doctrine because that has never been the government’s asserted justification for the provision, and because in that context too, the provision would be unconstitutionally overbroad insofar as it would bar the registration of marks containing the names of famous persons that do operate as source indicators.

While predicting the outcome of a Supreme Court case is always hazardous, it appears that if the Court is to follow its own First Amendment precedent, it must either declare section 1052(c) facially unconstitutional or formulate a test for the PTO to apply similar to the First Amendment defenses to the right of publicity, such that a substantial number of the statute’s applications do not violate free speech.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.