by Dennis Crouch

My recent discussion of Vanda v. Teva references the landmark Supreme Court case of Atlantic Works v. Brady, 107 U.S. 192 (1883). I thought I would write a more complete discussion of this important historic patent case.

Atlantic Works has had a profound impact on the development of patent law, particularly in shaping the doctrine of obviousness, but more generally providing theoretical frameworks for attacking "bad patents." As discussed below, I believe the case also provides some early insight into the new AI inventorship dilemma.

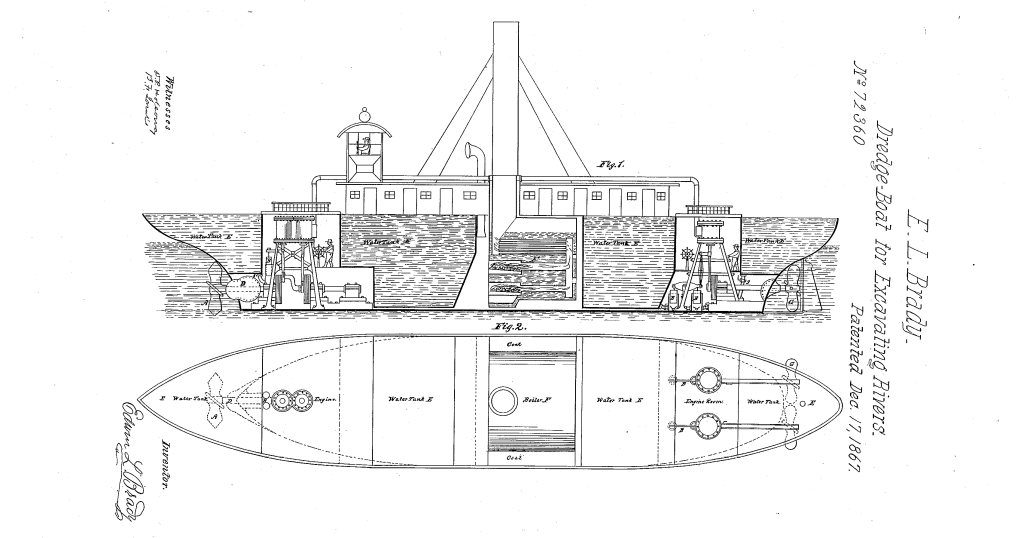

The case addressed the validity of a patent granted to Edwin L. Brady for an improved dredge boat design. The Supreme Court ultimately reversed the lower court's decision upholding the patent and found instead that Brady's claimed invention lacked novelty and did not constitute a patentable advance over the prior art.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.