Guest Post by Prof. Ted Sichelman, University of San Diego, School of Law

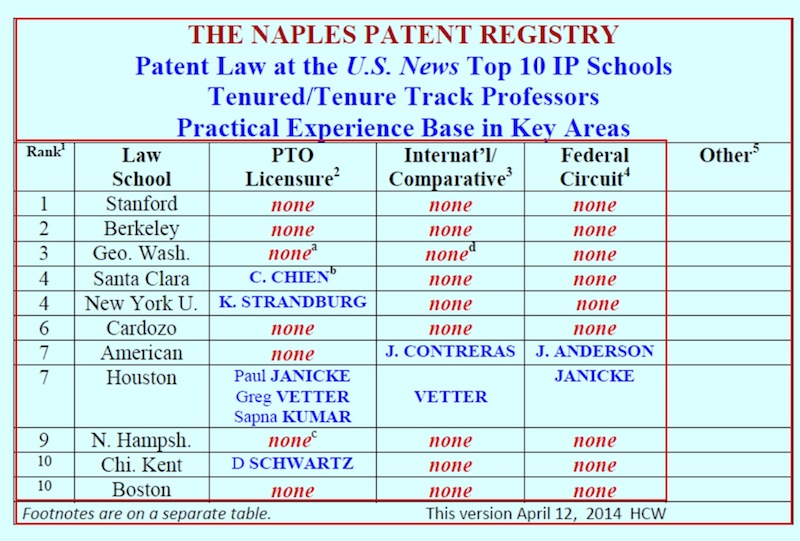

Recently, Hal Wegner has been circulating and commenting upon the qualifications of patent law professors. For example, he lists whether patent law professors at the Top Ten IP programs as ranked by US News & World Report are licensed to practice at the USPTO, have an “understanding” of international/comparative patent law, or clerked at the Federal Circuit (see below). According to Wegner, these “credentials” are “particularly” and “uniquely” valuable (in some cases, “essential”) for professors to make “optimum” patent policy reform proposals, especially those concerning PTO practice and international harmonization.

(To provide some background, I provided Wegner a list of names of all professors in the U.S. who currently teach and write about patent law at US News ranked and unranked IP programs, with the understanding that he would circulate the list to his readers. After I sent Wegner my list, without my input, he annotated it (along with other names) with various credentials and provided commentary and alternative lists, such as the one reproduced below. Because I believe Wegner’s analysis is flawed—and given my initial participation—I feel personally obligated to respond.)

Notably absent on Wegner’s list above are any professors from Stanford, Berkeley, and George Washington (GW), the top ranked IP programs in the nation. (The same holds true for many other schools, both in and outside of the top 10. I focus on the top three schools to underscore the problems with Wegner’s approach.) Rather than effectively denigrate these programs, Wegner should have recognized the transformative role that these schools have played historically (for GW) and more recently (for all three schools) in elevating patent law to a prominent place in the academy and developing unparalleled educational opportunities for future patent professionals and scholars.

Notably absent on Wegner’s list above are any professors from Stanford, Berkeley, and George Washington (GW), the top ranked IP programs in the nation. (The same holds true for many other schools, both in and outside of the top 10. I focus on the top three schools to underscore the problems with Wegner’s approach.) Rather than effectively denigrate these programs, Wegner should have recognized the transformative role that these schools have played historically (for GW) and more recently (for all three schools) in elevating patent law to a prominent place in the academy and developing unparalleled educational opportunities for future patent professionals and scholars.