by Dennis Crouch

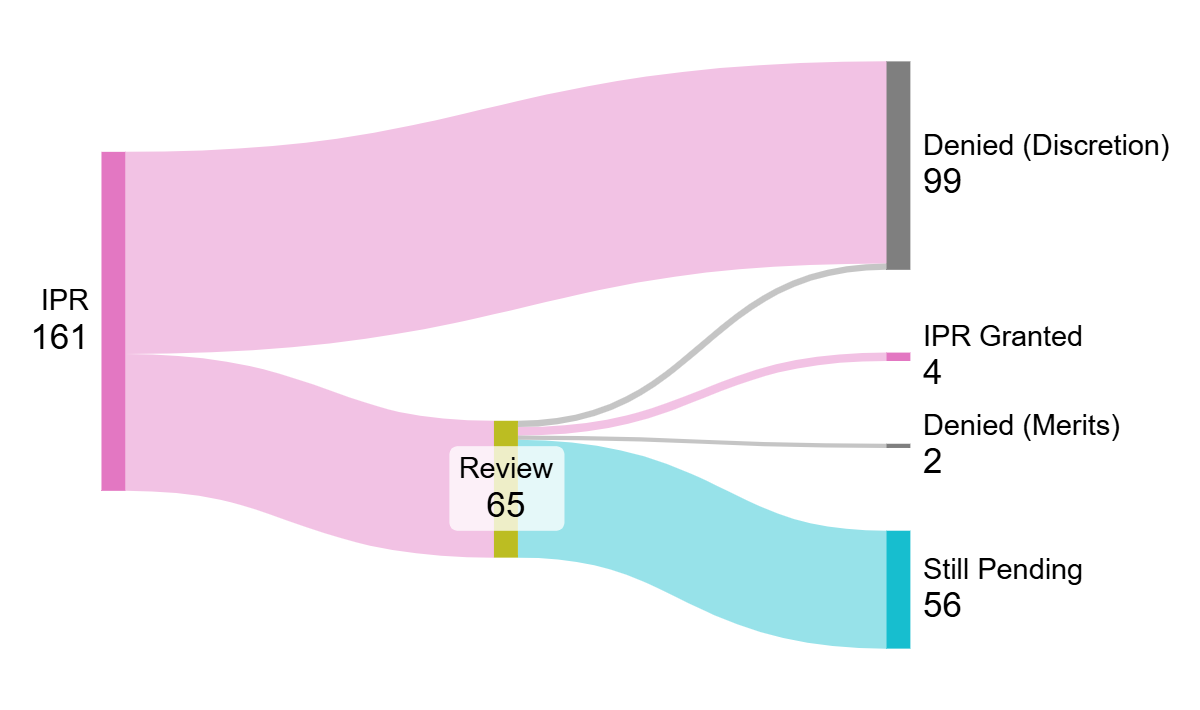

The Federal Circuit dismissed an interlocutory appeal in Micron Technology, Inc. v. Longhorn IP LLC, No. 2023-2007 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 18, 2025), finding no appellate jurisdiction over a district court order imposing an $8 million bond under the Idaho Bad Faith Assertions of Patent Infringement Act. This jurisdictional ruling delays what promises to be a consequential showdown over federal preemption.

Roughly thirty states have anti-patent-troll legislation -- mostly targeting bad faith demand letters. But, Idaho's is one of the more aggressive because it identifies filing a complaint (i.e., filing the lawsuit) as a potentially unlawful communication. That choice puts Idaho on direct collision course with federal patent law in ways that other state statutes have more carefully avoided. The problem is that patent law (supported by the U.S. Constitution) gives patentees the right to sue infringers for infringement. Under Federal Circuit precedent, state laws that impose liability based on patent enforcement activity are generally preempted unless the patent holder's assertions were objectively baseless and made in subjective bad faith.

The appellants in this case, Longhorn IP and Katana Silicon Techs, argued that Idaho's attempt to regulate federal court pleadings is facially preempted because such filings are governed by federal patent law. Micron and the State of Idaho responded that the state has the right and power to regulate bad-faith patent assertions, regardless of whether the assertion appears in a demand letter or a complaint. I listened in on the oral arguments and noted that the panel spent considerable time probing these questions. But, the court ultimately concluded it lacked appellate jurisdiction. So, we'll have to wait until final judgment we receive a clear appellate answer. And, it means that the patentee will need to pay the $8 million bond if it wants the infringement litigation to move forward.

More background:

Federalism on Trial: Idaho’s Attempt to Regulate Patent Litigation

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.