by Dennis Crouch

In a display of judicial frustration with attorney conduct, the Federal Circuit (i.e., Chief Judge Moore) recently confronted two appellants for apparently attempting to circumvent word count limitations through a "divide and conquer" briefing strategy. The parties have responded to the court's show cause order in Focus Products Group International v. Kartri Sales Co., and we are now waiting for the court to act both on the merits of the case and potential sanctions.

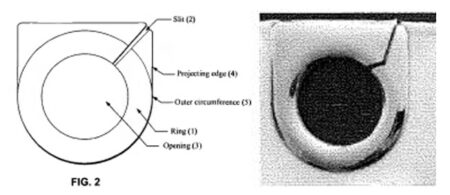

The conduct dispute centers on how appellants Kartri Sales and Marquis Mills structured their briefs in appealing a district court decision that found the parties infringed both patents and trade dress related to shower curtain designs. The case was heard before a Federal Circuit panel consisting of Chief Judge Moore, along with Circuit Judges Clevenger and Chen. Patrice Jean of Hughes Hubbard & Reed represented Kartri Sales, Donald Cox his own firm represented Marquis Mills, and Morris Cohen of Goldberg Cohen represented the Sure Fit appellees.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.