by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit’s en banc decision in EcoFactor v. Google marks a significant tightening of standards for admitting patent damages expert testimony. The court (in an 8–2 split) overturned a $20 million jury award by excluding the patentee’s expert evidence as insufficiently reliable under Federal Rule of Evidence 702 and Daubert. Writing for the majority, Chief Judge Moore treated what traditionally might have been viewed as a factual dispute over “comparable” license agreements as, instead, a matter of contract interpretation for the court. In doing so, the majority held that the trial judge failed in his gatekeeping duty by allowing the jury to hear an expert opinion founded on speculative leaps—namely, the assumption that prior licensees agreed to a particular royalty rate that was not reflected in the actual license terms. Two dissenting judges (Judges Reyna and Stark) each criticized the court for overstepping the proper scope of Rule 702 and for usurping the jury’s role in weighing evidence. As I discuss below, I believe that the dissents have the better view of this case. [Read the Decision]

I see this case as part of a crafted doctrinal transformation that I call the “Remedies Remedy,” that began with the Supreme Court’s undermining of injunctive relief in eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006) and was then followed by a series of Federal Circuit decisions tightening the requirements for proving monetary damages. For example, the court abolished the old 25% rule of thumb for royalties as arbitrary and unreliable (Uniloc USA, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 632 F.3d 1292 (Fed. Cir. 2011)), reinforced the requirement to apportion damages to the patented feature’s value (LaserDynamics, Inc. v. Quanta Computer, Inc., 694 F.3d 51 (Fed. Cir. 2012)), and demanded closer scrutiny of “comparable” license agreements used as benchmarks (Lucent Techs., Inc. v. Gateway, Inc., 580 F.3d 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2009); ResQNet.com, Inc. v. Lansa, Inc., 594 F.3d 860 (Fed. Cir. 2010)). The thrust of these cases is a clear message: patent damages must be grounded in sound economic reasoning and actual evidence, not rules of thumb or tenuous analogies. And, without sufficient expert testimony, juries will not be permitted to hear the evidence.

EcoFactor is a significant next step — Let me explain: Until now, the line between an expert’s unreliable “speculation” and a factual issue for the jury was often debatable. And, the focus of Daubert was on clear methodological shortcomings rather than factual shortcomings. For instance, in Summit 6, LLC v. Samsung Electronics Co., the court cautioned that district courts must not “step into the role of the factfinder” by rejecting an expert’s opinion simply because the underlying factual assumptions are contested or the methodology is not flawless. 802 F.3d 1283 (Fed. Cir. 2015). Judges were reminded that if the admissibility bar is set too high, “the trial judge no longer acts as a gatekeeper but assumes the role of the jury.” This tension between robust gatekeeping and respect for the jury’s domain set the stage for EcoFactor, the Federal Circuit’s first en banc utility patent case in years (and the first en banc on a patent damages issue since the late 1990s).

The Case and Panel Decision: Licenses, Lump Sums, and a $20 Million Royalty

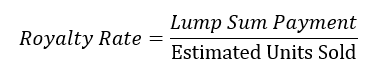

EcoFactor Inc. v. Google LLC centers on a smart thermostat patent (U.S. Patent No. 8,738,327) that EcoFactor asserted against Google’s Nest thermostats. In the trial before Judge Alan Albright (W.D. Tex.), EcoFactor relied on a reasonable royalty theory for damages. EcoFactor’s damages expert, David Kennedy, testified to a royalty of “$X” per unit (the exact rate is sealed) and opined that this rate was justified by three prior license agreements EcoFactor had executed with third parties. Each of those agreements was a litigation settlement license in which EcoFactor granted a portfolio license (covering the ‘327 patent among others) for a one-time lump sum payment. Importantly, Mr. Kennedy derived the $X-per-unit figure by dividing the lump sums by estimated unit sales – effectively converting each lump-sum deal into an implied running royalty. In doing so, he also leaned heavily on “WHEREAS” clauses in the agreements reciting that EcoFactor believed the lump sum was equivalent to $X per unit. He then told the jury that because “other people have paid” $X per unit for this technology, Google should pay the same rate.

This approach was provocative on several levels. First, the licenses were “performative” settlement agreements, crafted during litigation. Two of them (with Daikin and Schneider) explicitly stated in the operative provisions that the lump sum “is not based upon sales and does not reflect or constitute a royalty”. In other words, the contract itself disclaimed any agreed running royalty rate. The third license (with Johnson Controls) was similarly structured and, moreover, resolved litigation that did not even involve the ‘327 patent (though the license covered EcoFactor’s entire portfolio, including ‘327). Google argued that Mr. Kennedy’s methodology was fundamentally flawed: he ignored the actual license terms, which showed at most EcoFactor’s unilateral asking rate and expressly rejected any per-unit royalty basis. Furthermore, the expert made no effort to isolate the value of the ‘327 patent in these multi-patent deals, simply asserting that various unquantified “upward and downward” adjustments (accounting for the portfolio scope and the litigation context) would cancel out. However, Google’s contentions were in the form of attorney argument; Google did not present its own damages expert, instead relying on cross-examination to undercut EcoFactor’s case.

The jury found Google liable for infringement and awarded $20 million in damages, essentially adopting EcoFactor’s theory. Google moved post-trial to set aside the verdict or get a new trial, citing the judge’s refusal to exclude Kennedy’s testimony under Rule 702. Judge Albright denied these motions, and Google appealed. A Federal Circuit panel majority authored by Judge Reyna and joined by Judge Lourie affirmed the damages award, taking a deferential view of the trial court’s gatekeeping discretion. The panel acknowledged the comparable license analysis was imperfect but concluded that the expert’s opinion was “sufficiently reliable for admissibility purposes” and had “sufficiently apportioned” the ‘327 patent’s value to go to the jury. Echoing the traditional stance, the panel emphasized that Google’s critiques went to the weight of the evidence: challenges to the comparability of license agreements raise “factual issues best addressed by cross-examination and not by exclusion”. The majority cautioned that courts should not raise the admissibility bar so high that the judge usurps the jury’s role. In dissent, Judge Prost sharply disagreed, arguing that the expert’s method “lacked rigor” and failed to show the licensees actually agreed to pay any per-unit royalty, thereby relying on EcoFactor’s self-serving assertions in the contract recitals. Prost would have found an abuse of discretion in admitting the testimony, faulting the absence of any concrete evidence linking the lump-sum payments to the $X rate.

Google’s petition for rehearing en banc was granted – a rare move (this was the Federal Circuit’s first en banc rehearing in a utility patent case since 2018). Although there were other issues with the expert testimiony, the en banc court limited the scope of review to the Rule 702/Daubert issue concerning the expert’s per-unit royalty analysis based on the three licenses. Google’s additional arguments about apportionment and other matters were explicitly set aside. Thus, the stage was set for the full court to address a focused evidentiary question: Did the district court properly discharge its gatekeeping duty under Rule 702 in allowing the jury to hear Mr. Kennedy’s damages testimony?

I want to pause for a moment to note that this whole setup and issue is pretty ridiculous.

The expert conducted one of the simplest financial calculations: moving between a total-value (lump sum) to a per-unit-value (royalty rate). Just like price-per-gallon is the standard measure for gas prices, the per-unit royalty is the most accepted standard for license rates. That calculation is simple lump sum payment divided by the number of units sold.

There are several reasons to use lump sum payment in actual deals – the key is that they avoid any actual accounting, and here the expert used an estimated number of units licensed to calculate the licensee royalty rate. The contracts did expressly state that the lump sum was not a royalty rate, but that clause is common in contract for a variety of reasons. As suggested above, it avoids the need for any actual accounting and reduces future litigation risk by agreeing upon a sum-certain — they pay once and are done. In addition, lump sum agreements at times can have separate tax and accounting advantages.

What this means to me is that—while it would be better evidence if the contracts explicitly stated the per-unit royalty calculation—the expert’s simple conversion from lump sum to per-unit rate should not be summarily excluded and itself appears sufficient as the most obvious and reliable starting point. It is precisely the kind of standard economic inference routinely presented to juries, who can weigh any counterarguments about the disclaimers, negotiations, or market conditions through cross-examination and competing testimony. The presence of boilerplate disclaimers does not negate the economic reality that lump-sum payments are almost always set with underlying unit sales projections in mind. Thus, treating this straightforward economic inference as fundamentally unreliable and removing it from jury consideration not only defies common practice but also undermines the jury’s role as factfinder in patent valuation disputes.

Back to the case: The En Banc Majority: Contract Interpretation as Gatekeeping

Chief Judge Moore’s majority opinion (joined by seven other judges) held that Mr. Kennedy’s testimony attributing an $X per-unit rate to the prior licenses should have been excluded as unreliable, and it ordered a new trial on damages. At its core, the majority’s analysis recharacterized the issue of license comparability – usually a factual question – into a question of law about contract meaning. Judge Moore began by reaffirming that contract interpretation, including whether a contract is ambiguous, is a question of law reviewed de novo on appeal. Applying the governing state laws (all three licenses had choice-of-law clauses, though the majority did not dwell on any differences), the court found no ambiguity in the license language: the plain text “expressly rejects” the idea that the lump sums were based on a per-unit royalty. In each agreement, the whereas clause memorialized only EcoFactor’s belief that $X per unit was a reasonable royalty, while the operative clause disclaimed any such basis for the payment. From this, the court drew two decisive conclusions:

- No Factual Support for “Licensee Agreed to $X”: Because the contracts themselves negate any agreement by the licensee to per-unit royalties, there was literally no evidence in the record that the licensees shared EcoFactor’s $X-per-unit valuation. At best, the licenses showed what EcoFactor (the licensor) would have accepted, not what the licensee actually agreed upon. The majority underscored that “the plain language of the license agreements does not support Mr. Kennedy’s testimony” that Daikin, Schneider, and Johnson Controls had agreed to an $X/unit rate– in fact, “the Daikin and Schneider licenses expressly disavow it.” The majority flatly rejected the suggestion (raised in Judge Stark’s dissent) that a licensee might have implicitly agreed to use the $X rate in calculating the lump sum while merely disputing its reasonableness. According to the majority, such an interpretation was foreclosed by the unambiguous disclaimer: “[Such lump-sum] amount is not based upon sales and does not reflect or constitute a royalty.” In short, no reasonable reading of the contracts allowed the inference that those companies “agreed to pay the $X royalty.”

- Expert’s Basis Was “Untethered” to the Evidence: Given the contract interpretation, the majority concluded that Mr. Kennedy’s opinion lacked the “sufficient facts or data” that Rule 702 requires. An expert cannot bridge an evidentiary gap with speculation or by parroting a client’s say-so. Here, the only support for the $X rate having been used was EcoFactor’s CEO’s testimony – and that too collapsed under scrutiny. CEO Shayan Habib had asserted that each license’s lump sum was calculated by multiplying $X by the licensee’s estimated sales. But Habib admitted he had no actual sales data or documentation from those companies to substantiate this calculation. In fact, neither Habib nor the expert ever saw the licensees’ sales figures; Habib claimed a “general understanding” of the industry as the origin of $X, and nothing more. The majority pointedly noted that Habib’s testimony “referenced no evidentiary support” – no actual or projected sales numbers – and he conceded that apart from his own say-so, he had “no other information” on how the lump sums were set. In the majority’s view, Habib’s testimony boiled down to an “unsupported assertion from an interested party” that $X was used – precisely the kind of unverified, result-driven assumption that cannot prop up an expert opinion.

Rule 702, especially as clarified in its 2023 amendment, demands that the proponent of expert evidence show a reliable factual foundation – the expert’s “relied-upon facts or data” must themselves be sufficient. According to the majority, that requirement was not met. And, as a consequence, the district court abused its discretion in failing to exclude this portion of his testimony. This, the court explained, is the essence of the judge’s gatekeeping role under Rule 702: to ensure the expert isn’t presenting a conclusion that no reasonable jury could reach from the actual evidence.

Judge Moore took pains to say that this analysis is not intended to “usurp the province of the jury, nor does it involve . . . deciding disputes of fact.” In the majority’s view, there were no genuine factual disputes here to leave to a jury – the contracts’ meaning was clear, and EcoFactor had proffered no factual data that the licensees used the $X rate.

The en banc decision prompted two dissenting opinions, one by Judge Reyna (joined by Judge Stark) and one by Judge Stark (joined by Judge Reyna). While both dissents agreed with the majority on issues unrelated to damages (and agreed that en banc consideration was proper despite EcoFactor’s objection to the absence of Judge Newman), they parted company with the majority’s handling of the Rule 702 issue. In broad strokes, the dissents fault the majority for (1) venturing beyond the question presented and reframing the issue as contract interpretation without adequate notice, and (2) undermining the traditional divide between admissibility and weight, thereby intruding on the jury’s fact-finding role. They also contend that, even accepting the majority’s critique of Mr. Kennedy’s analysis, the error was at most harmless given the other evidence.

Judge Reyna’s Dissent: Judge Reyna, author of the original CAFC decision, chastised the majority for a “sudden shift” in focus that “abandons the scope” of what the en banc court agreed to decide. The en banc order had limited review to the district court’s adherence to Rule 702/Daubert concerning the expert’s use of the licenses. In Reyna’s view, this implied examining whether admitting the testimony was an abuse of discretion under the usual multifactor Daubert framework – e.g., considering reliability of methodology, factual basis, etc. – not declaring, as a legal matter, what the licenses mean. By reframing the core issue as one of “contract interpretation as a question of law,” the majority decided the case on a theory that was never briefed or argued by the parties. EcoFactor, the dissent noted, had no notice that it needed to litigate contract meaning; indeed, neither party argued that contract interpretation was at issue in the Rule 702 analysis. Reyna expressed concern that this lack of notice and opportunity to be heard is fundamentally unfair to EcoFactor. He further pointed out that if the en banc court wanted to make contract law the centerpiece, it should have expanded the scope and allowed supplemental briefing – especially since the licenses were governed by different state laws (Massachusetts, New York, etc.), which the majority did not even discuss.

Judge Reyna then argued that the majority’s “new theory” was not necessary to resolve the case and, in fact, led the court astray from the real issue: how much discretion do trial judges have under Rule 702 to admit expert opinions that involve underlying factual judgments? He observed that the majority “speaks to Rule 702 and Daubert only when reciting well-known law”, but then bypasses the hard question of applying that law to a complex factual record in favor of a narrow contract-law ruling. Crucially, Reyna argued that even accepting the majority’s contract interpretation (that the evidence of an agreed $X rate was nil), Google still did not show that letting the testimony in harmed the trial result. Here, Reyna contended, any error was harmless because the same bottom-line royalty number ($X per unit) was supported by other, properly admitted evidence – for example, EcoFactor’s own belief and willingness to license at that rate. He noted that much of Mr. Kennedy’s testimony (and underlying evidence) was dedicated to establishing that $X was a reasonable royalty from EcoFactor’s perspective and that the technology was comparable, etc., which are permissible and were unchallenged. The offending piece – implying that licensees agreed with $X – was arguably cumulative of the overall picture that $X was a going rate EcoFactor was charging.

Judge Stark’s Dissent: Judge Stark (the newest member of the court, and the only former district judge on the bench) wrote separately to emphasize the narrowness of the majority’s holding – and to voice concern about potential misreading of the decision. He agreed with Reyna that the majority opinion has “very little to say about Rule 702 and Daubert” as such. In fact, Judge Stark read the holding as “so narrow as to have almost no applicability beyond this case.” In his view, the majority essentially decided that on this unique record there was no evidence to support a critical premise of the expert’s opinion, making the testimony indefensible. Judge Stark granted: “If I shared [the majority’s] view of the record, I would join the Majority Opinion.” He agreed that no court should admit expert testimony “unquestionably at odds” with the evidence. But Stark did not share the majority’s take on the record. Echoing Reyna, he believed there was “sufficient evidence supporting Mr. Kennedy’s belief that one or more of EcoFactor’s licensees agreed to an $X rate.” In other words, he would not characterize the evidence as so one-sided; perhaps the licenses and circumstances could support competing inferences (e.g. maybe at least one licensee effectively used $X in negotiations). This difference in reading the record is itself telling: Stark’s point is that reasonable minds (even judges) could disagree on what inference to draw, which suggests the issue is a factual one suitable for the jury.

Judge Stark’s larger worry is one that I share – that the decision could be interpreted as imposing new, broad constraints on damages experts or inviting judicial factfinding under the guise of reliability. He stressed that EcoFactor should be understood to govern only extreme cases – specifically, “where an expert’s testimony is undoubtedly contrary to a critical fact” and thus no reasonable jury could find the fact as the expert assumes. In the “vast majority of patent cases,” he observed, experts will be dealing with evidence that “can support competing conclusions”, and in those situations the case is inapplicable. This is an important caveat, essentially limiting the majority’s reach to its unusual facts. Of course, the majority opinion does not itself include this caveat.

Unlike Stark’s characterization, the majority doesn’t include language suggesting this applies only to extreme cases or should be narrowly construed. And, the risk here in Judge Stark’s view is that litigants may read the decision as permitting (even requiring) judges to “invade the province of jurors and resolve fact disputes” whenever they assess expert admissibility. He noted with regret that the majority “seem[s] to have opened the door to turning Rule 702 into a vehicle for judicial resolution of fact disputes, at least with respect to damages experts.” Stark emphasized that disputed facts are not the same as insufficient facts under Rule 702. Where experts rely on different factual assumptions or interpret evidence differently, it is not the judge’s job to declare one set “right” and exclude the other. A reliable methodology can yield different conclusions depending on which facts are credited – deciding which facts are true is the jury’s role.

The Doctrine: Ultimately, EcoFactor represents the Federal Circuit’s most forceful statement yet that trial judges must actively police the foundation of damages experts’ opinions, especially when the disputes intertwine with traditionally factual matters like license comparison. Going forward, we can expect accused infringers to more aggressively challenge damages experts who base their royalty calculations on licenses or other data that are arguably distinguishable or not transparently tied to the patent-in-suit. District judges, for their part, may feel compelled to hold pre-trial Daubert hearings that scrutinize not just the methodology in the abstract but the factual underpinnings of each step in the analysis.

As mentioned above, EcoFactor also continues the Federal Circuit’s ongoing recalibration of the roles in damages cases. Traditionally, a district court’s decision to admit or exclude expert testimony is reviewed for abuse of discretion (with considerable deference). The twist in EcoFactor was to characterize the key issue as a question of law – contract interpretation – which is reviewed de novo. By doing so, the appellate court effectively gave itself a freer hand to override the trial judge’s judgment. In patent law, there are a good number similar issues of law (i.e., obviousness, enablement etc), that may draw in the technical experts as well. This may set a precedent for parties to frame over experts in legal terms to avoid the high hurdle of abuse-of-discretion review.

Ultimately, although I prefer the dissenting opinions, it is the majority’s decision that will be cited frequently in future Daubert motions and appeals.

On remand, I expect that EcoFactor’s damages expert will subtly but significantly reframe the testimony to avoid the Federal Circuit’s core objection. Rather than asserting that the prior licensees “agreed to pay $X per unit” – which the majority characterized as an unsupported factual claim about licensee intent – the expert will likely present the analysis as a standard methodological approach for normalizing different license structures. This reframing transforms the testimony from making contested assertions about what historical parties subjectively intended into applying recognized analytical methods to objectively determine comparable economic values. The expert can explain that just as commodities are compared on a price-per-pound basis and gasoline on a price-per-gallon basis, patent licenses are routinely analyzed on a per-unit basis to enable meaningful comparisons across different deal structures. This methodology doesn’t require divining the licensees’ subjective intent; it simply applies standard economic analysis to publicly available contract terms.

This approach should survive the Federal Circuit’s scrutiny because it addresses the court’s fundamental concern while building on principles the majority explicitly endorsed. The court noted that reasonable royalty analysis “necessarily involves an element of approximation and uncertainty” and that “there may be more than one reliable method for estimating a reasonable royalty.” More importantly, the majority acknowledged that the licenses remain “relevant to a reasonable royalty analysis” and could properly show “the amount that EcoFactor would have accepted as a willing licensor” under the Georgia-Pacific framework. By presenting the per-unit conversion as an analytical tool rather than evidence of licensee agreement, the expert can rely on these same licenses while avoiding the evidentiary gap that doomed the original testimony. The key distinction is that this approach doesn’t claim the licensees actually agreed to anything beyond the lump-sum payments – it simply applies industry-standard methodology to determine what those payments represent on a normalized basis.

Additional notes:

- Judge Lourie flipped sides from the original panel decision to the en banc majority, I speculate he was influenced by the contract interpretation framing that was not addressed in detail in the original opinion.

- Judge Newman was excluded from participating in the decision. Her exclusion was challenged, but the en banc majority concluded that the suspension was authorized by Congress and thus permitted the panel to proceed without Judge Newman, reasoning that Congress intended such suspensions to apply even in significant cases requiring en banc review.

- Judge Cunningham also did not participate in the case.

- Twenty-one amicus briefs!

- The actual royalty rate ($X) remains under seal.

Patent infringement damages calculations do not seem to me to be made much more realistic just by denying expert opinion evidence based on statements in preamble clauses in licenses to others for cash settlements. Cash settlement licenses are often actually primarily based on the litigation cost savings of the defendent accomplished by settling. I.e., to avoid the high costs of litigating a full blown jury trial on all possible issues, and the appeal, even if the patent seemed vulnerable to the defendant. That reality is ignored here.

Here, we also have a favorable patent validity and infringement decision below sustained on appeal. Logically [but presumably not?] that should allow the patent owner to collect much higher royalty-rate-based damages on remand for the willful infringements occuring after the infringer loses on alleged invalidity and non-infringement irrespective of prior pre-trial-settlement licenses?

Right. I take issue with the idea that

Lump Sum Payment = Royalty Rate * Estimated Units Sold

The actual formulation should also account for fixed benefits, those that are independent of units sold:

Lump Sum Payment = Fixed Benefits + (Royalty Rate * Estimated Units Sold)

Fixed benefits includes things like avoiding the costs of litigation as mentioned above, avoiding the uncertainty of the damages lottery in litigation, having freedom to innovate future products (particularly with portfolio licenses), etc. I do not think it credible to opine that there are *no* fixed benefits for a lump sum license, as the patent holder’s expert did here. Whether that rises to the level of a 702 exclusion is a question I leave to more damages-oriented folks. 🙂

Thanks, and the lesson may be that such fixed benefit questions should be part of the cross-examination of the patent damages expert?