By Sarah Burstein, Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

Gamon Plus has filed a petition for rehearing in its design patent dispute against Campbell (previous Patently-O coverage of the case by Professor Crouch here).

Like the majority and the dissent in the panel decision, the petition does not directly address the main difficulty raised by this case—namely, how should we apply the design patent “primary reference” test for multi-article designs?

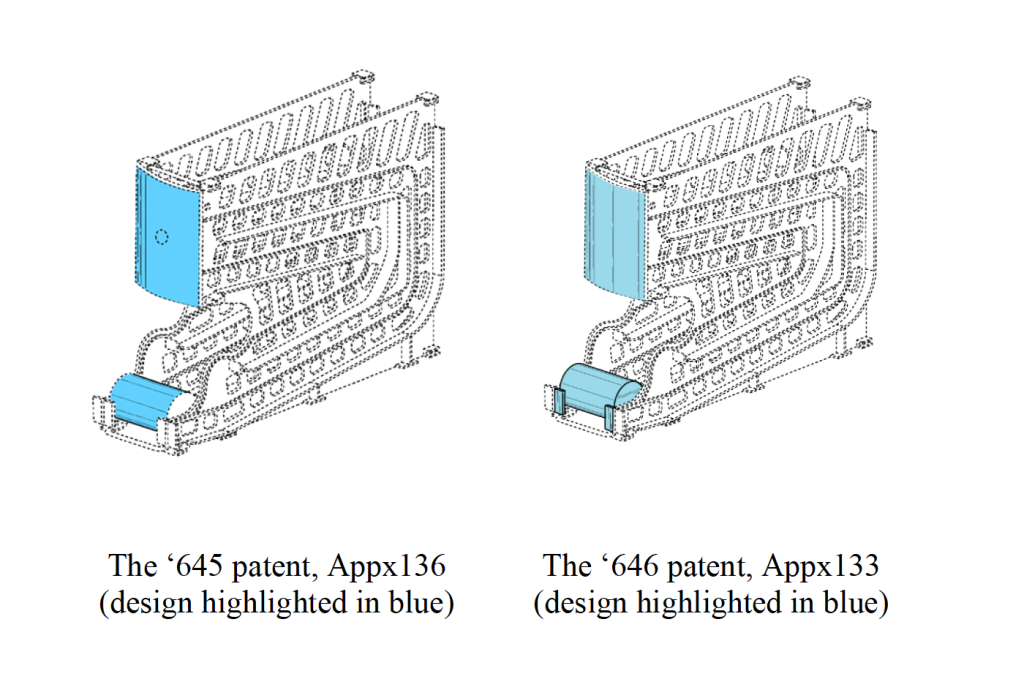

According to Gamon Plus, its two patents claim “designs of displays developed by Appellee Gamon Plus specifically for the display of Campbell Soup cans in stores.” Here are the illustrations Gamon Plus included in its petition for rehearing:

However these claims are interpreted (a matter of much dispute in this case), they are each clearly directed to what we might call a “multi-article” design. Each design defines parts of the shapes of separate articles—a dispenser and a can.

The problem is that the design patent “primary reference” requirement was created in the context of—and implicitly assumes—a single-article design. The lesson in Durling and Rosen was that you can’t create a Franken-article to serve as a primary reference. If the patent (or application) claims a design for a table, you can’t splice parts of different tables together to form a single, hypothetical table. You have to find a table that actually exists (or a sufficient description thereof) in the prior art.

But what happens when the design extends over separate articles? Gamon Plus (and Judge Newman, in dissent) seem to argue that there must be a single reference that explicitly discloses both articles being used together in the same way. That can’t possibly be right—especially on the facts of this case.

Gamon Plus conceptualizes its design as a “display” with a label and a can with “specific dimensions” is placed “at a specified relative location spaced below the [dispenser] label.” But Gamon Plus didn’t invent that can shape. To the contrary, as quoted above, Gamon Plus says the dispenser was designed specifically for Campbell’s Soup cans.

The only shape that Gamon Plus invented was the shape of the dispenser. That shape may be defined by and adapted to the shape of the can. And it may be meant to display that can in a particular position. But a patentee should not be able to effectively immunize a design for one article from § 103 scrutiny merely by claiming the “design” is really the use of that article with some other (unoriginal) article.

Whether inherency is the best way to get at these issues is another question. Perhaps, when it comes to multi-article designs, the primary reference test should be applied on an article-by-article basis. Or maybe § 171 should be interpreted to exclude multi-article designs. But in any case, it would be nice to see the Federal Circuit confront these issues directly.

= = = =

Side note: As someone who’s studied design patent nonobviousness for a long time, the thing I found most surprising thing about this decision was that the majority thought Linz looked similar enough to be a primary reference—hypothetical can or no hypothetical can. In recent cases, it’s been hard to see much blue sky between “basically the same” (the primary reference standard) and “the same” (the anticipation standard), at least as the former is applied by the Federal Circuit. For more on some of these cases, and design patent nonobviousness more generally, see this article and this post. If Campbell signals a shift away from that overly strict application of the test, that would be a welcome development.

There’s nothing “ornamental” about these claims. Any analysis beyond that is just w@-nkery. I mean have it if you’ve got the time to waste. Rich white guy problems and all that.

The entire US design patent system needs to be burned to the ground and the fuel should be David Kappos’ closet full of u-g-l-y cologne-soaked suits.

… white …?

“The entire US design patent system needs to be burned to the ground and the fuel should be David Kappos’ closet full of u-g-l-y cologne-soaked suits.”

said MM before taking a bite of caviar.

…let them eat cake…(?)

Per the last paragraph above, see also “Design Patents §103 – Obvious to Whom and As Compared to What?” Patently-O, Sept. 17, 2014.

Re: “Gamon Plus (and Judge Newman, in dissent) seem to argue that there must be a single reference that explicitly discloses both articles being used together in the same way. That can’t possibly be right.” Indeed, especially since it violates the Sup. Ct. interpretation of §103.

Not saying that you are wrong (or right), but how exactly is the view as to what constitutes a primary reference (on its own, without even venturing to any secondary references at all); remotely one point to any Supreme Court precedence?

Damm autocorrect….

one point => on point

In particular, the facts and holdings of the controlling authority on §103 obviousness, KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 127 S. Ct. 1727, 1733 (2007), even though §103 by statute applies to design patents. At least one D.C. judge has note out the [blatent] total ignoring of that Sup. Ct. decision in design patent decisions.

Great. I understand utility obviousness and the Supreme Court’s scrivening in KSR.

I also understand the general maxim of “design patents are adjudged under 35 USC 103 just as utility patents are.”

What you have not done (as of yet) is actually link any Supreme Court case to your proposed point here.

The facts (especially) and holding of KSR do not intersect with the musings of the facts and case here by way of what constitutes a primary reference prior to considerations of combination of references (at which point the KSR case may then have something to say).