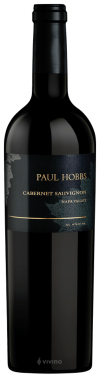

The Federal Circuit's recent decision involving Paul Hobbs and Hobbs Winery raises a number of important issues for anyone investing in celebrities or influencers. In the case, early investors in Hobbs Winery were unable to prevent Mr. Hobbs from using his name in other wine ventures, even though a registered mark on PAUL HOBBS was owned by Hobbs Winery. This case was decided on statutory grounds - with a holding that minority owners in a company are not authorized to bring a TM cancellation to protect a mark held by the company. This is an important decision because it prevents the TTAB from being used to settle internal corporate management issues.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.