A recently filed petition for writ of certiorari in Lemon Bay Cove, LLC v. United States highlights the longstanding difficulty in defining regulatory taking as well as determining when a regulatory takings claim becomes ripe for judicial review. The brief was filed by the Pacific Legal Foundation, a public interest law firm that focuses largely on protecting private property against government intrusion and regulation.

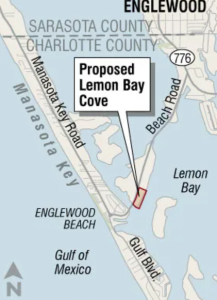

Background: Lemon Bay Cove, LLC owns about 6 acres of intercoastal property in Charlotte County, Florida, north of Ft. Myers. In 2012, Lemon Bay applied to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for a permit to fill about 2 acres around Sandpiper Key to construct a 12-unit townhome development. After a nearly four-year process, the Corps denied the application with prejudice in 2016.

Lemon Bay then filed suit in the Court of Federal Claims, alleging that the Corps' denial effected a per se regulatory taking under Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council, 505 U.S. 1003 (1992), by depriving the property of all economically viable use.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.