by Dennis Crouch

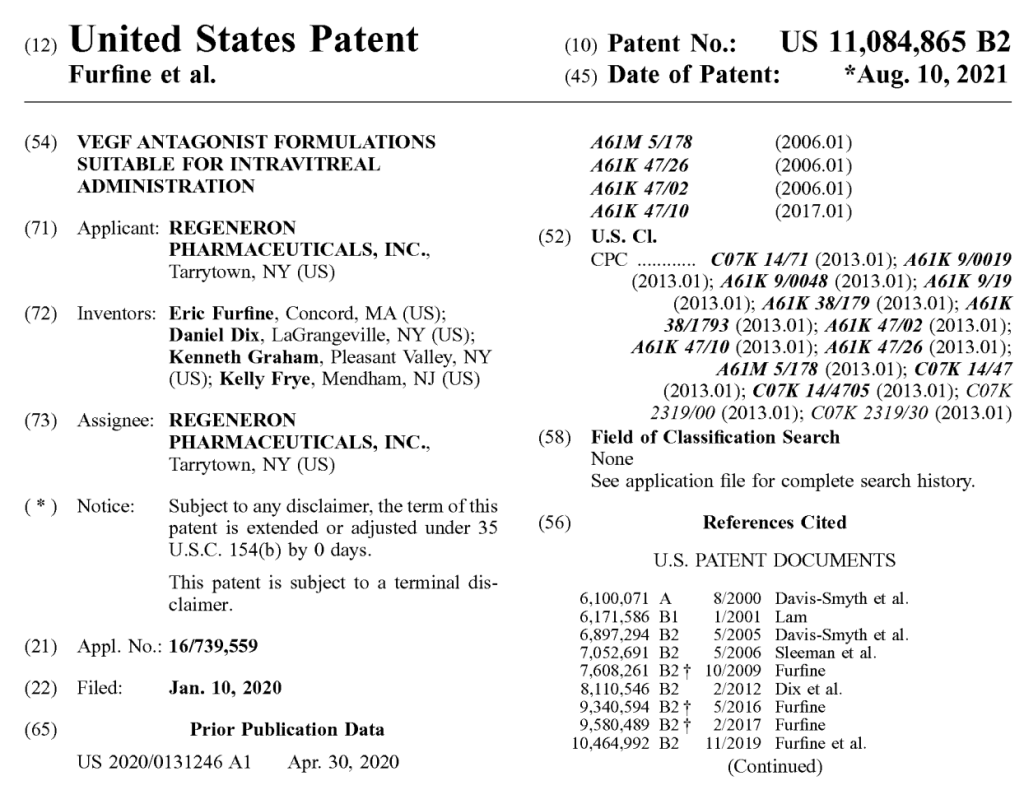

In a pair of significant decisions issued today, the Federal Circuit upheld preliminary injunctions blocking the launch of biosimilar versions of Regeneron’s blockbuster drug EYLEA® (aflibercept). Regeneron Pharms., Inc. v. Mylan Pharms. Inc., No. 2024-1965 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 29, 2025) (precedential); and Regeneron Pharms., Inc. v. Mylan Pharms. Inc., No. 2024-2009 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 29, 2025) (nonprecedential). The cases pit Regeneron against foreign manufacturers, including Samsung Bioepis (SB) and Formycon AG, who had obtained FDA approval for their biosimilar products under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA). Writing for a unanimous panel, Judge Taranto focused on three key issues: (1) personal jurisdiction over foreign biosimilar manufacturers; (2) obviousness-type double patenting in the biologics context; and (3) standards for preliminary injunctive relief. The decisions effectively maintain Regeneron’s market exclusivity for EYLEA®, which generates approximately $6 billion in annual sales and serves as a primary treatment for several serious eye conditions including wet age-related macular degeneration. U.S. Patent No. 11,084,865.

The cases reached the Federal Circuit after WV Chief Judge Kleeh granted preliminary injunctions barring both SB and Formycon from launching their FDA-approved biosimilars. While the appeals involved several patents, focus is on the ‘865 patent linked to above. The key claim limitations require that the formulation maintain “at least 98% of the VEGF antagonist . . . in native conformation following storage at 5° C for two months” and that the protein be “glycosylated.”

More details on the invention: The drug aflibercept is a fusion protein made by combining parts of different proteins that combine to act as a VEGF-antagonist, meaning it binds to and blocks vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF promotes the growth of blood vessels. It is that blood vessel growth that can damage vision for people with wet age-related macular degeneration. Aflibercept binds to VEGF and thus prevents it achieving its natural outcome.

The BPCIA provides an abbreviated pathway for FDA approval of biosimilar products while balancing innovator patent rights through complex litigation provisions. Under 42 U.S.C. § 262(l), biosimilar applicants provide their applications to the reference product sponsor and engage in a structured “patent dance” to resolve patent disputes before launch. Like Hatch-Waxman, BPCIA creates an artificial act of infringement when a party submits a biosimilar application, allowing suits like Regeneron’s to proceed before actual sales begin. 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2)(C). This framework formed the backdrop for the court’s analysis of both personal jurisdiction and the preliminary injunctions.

BCPIA Personal Jurisdiction over Foreign Manufacturers: A central issue on appeal was whether the district court properly exercised personal jurisdiction over foreign manufacturers who planned to market their products through U.S. distributors. The Federal Circuit had previously addressed similar questions in the small-molecule generic drug context in Acorda Therapeutics Inc. v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc., 817 F.3d 755 (Fed. Cir. 2016), and this case extends that reasoning to biologics. The appellate panel confirmed that (1) filing a biosimilar application combined with (2) plans for nationwide distribution through a U.S. partner creates sufficient minimum contacts to support jurisdiction.

If you recall, the Supreme Court requires a state-focused analysis of personal jurisdiction. And, the key state to consider is the state where the district court is located. Here, there were apparently no specific plans to sell the product in West Virginia, but the court still found that the WV court properly exercised personal jurisdiction based upon a stream of commerce theory. Quoting Acorda, “And even if [accused infringer] does not sell its drugs directly into [the forum state], it has a network of independent wholesalers and distributors with which it contracts to market the drugs in [the forum state]. Such directing of sales into [the forum state] is sufficient for minimum contacts.”

The court rejected attempts by the accused infringers to distinguish Acorda based on their use of exclusive U.S. distributors who controlled substantial aspects of the distribution process. While this theory may have some legs, Judge Taranto emphasized that both companies maintained significant ongoing involvement in U.S. commercialization through various contractual mechanisms, including participation in joint steering committees. The court also found particularly relevant that neither company had carved out the forum state from their distribution plans, suggesting an intent to serve the entire U.S. market.

Obviousness Type Double Patenting (ODP): The Federal Circuit’s analysis of obviousness-type double patenting highlights an ongoing challenge of evaluating follow-on patents in the biologics space. ODP is a judicially-created doctrine designed to prevent improper patent term extensions by obtaining multiple patents, each with claims that are not “patentably distinct” from one another. The doctrine requires a two-part analysis discussed in AbbVie Inc. v. Kennedy Institute, 764 F.3d 1366, 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2014): first comparing the claims of the earlier and later patents to identify differences, then determining whether those differences render the claims patentably distinct. The court emphasized that while this analysis is “analogous to an obviousness analysis under 35 U.S.C. § 103,” it differs critically because “the nonclaim portion of the earlier patent ordinarily does not qualify as prior art against the patentee.”

Here, the patentee previously obtained now-expired U.S. Patent No. 9,340,594 that also covered VEGF-antagonist drug. Here, though the court found that the claims were different enough to avoid ODP problems. In particular, the new patent included what the court found were two key claim limitations: the requirement for 98% stability in native conformation and the glycosylation requirement. According to the court, these represented more than mere “additional properties” of the composition claimed in the older patents. Judge Taranto found particularly significant the district court’s unchallenged findings that a skilled artisan would have lacked motivation to achieve 98% stability and would have actually been motivated to avoid glycosylation due to concerns about retinal penetration and inflammation risk.

I think here that the challengers were seeking something like an inherency finding without actually having to prove up the issue. Certainly Chief Judge Moore who was also on the panel would not have permitted that outcome. While the ‘594 patent broadly claimed “stable” formulations, the court held this did not inherently disclose the specific 98% native conformation requirement, particularly given the old specification’s teaching of a preferred stability level of “at least 90%” and discussion of multiple aspects and measures of stability.

Preliminary Injunction Standards: Finally, in its analysis of the preliminary injunction, the court focused on the requirement to show a causal nexus between infringement and irreparable harm absent injunctive relief. The court distinguished this case from complex multi-feature products like smartphones, explaining that “[t]he causal-nexus inquiry [here] may have little work to do in an injunction analysis when the infringing product contains no [additional] feature relevant to consumers’ purchasing decisions other than what the patent claims.” In other words, it is easier for a pharma company to get injunctive relief.

Public Interest Factor: While acknowledging the general public interest in access to lower-cost medicines, the court found that interest outweighed by the need to protect valid patent rights and maintain innovation incentives in the biologics space.

In the end, the Federal Circuit’s dual decisions here both preserve Regeneron’s multi-billion dollar Eylea franchise and also strengthen the foundation for biological drug patent enforcement against foreign manufacturers in U.S. courts.