by Dennis Crouch

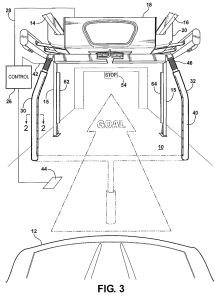

The Federal Circuit’s March 2025 decision in Wash World v. Belanger, attempts to clarify an important distinction between apportionment and convoyed sales in patent damages jurisprudence, dissolving nearly $2.6 million from a jury’s $9.8 million lost profits award. Wash World Inc. v. Belanger Inc., No. 2023-1841, slip op. at 26 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 24, 2025). A jury found that Wash World’s “Razor EDGE” car wash system infringed Belanger’s U.S. Patent No. 8,602,041, which claimed a vehicle spray washer with lighted spray arms. Adding lights is a simple transformation, but apparently the particular arrangement of flashing lights running down the length of each during vehicle entry to create a “goalpost effect” that guides drivers to position their vehicles.

The infringed claim covers a “a spray-type car wash system” that expressly recites a carriage and spray arms with their lighting system. Although other components such as dryers are traditionally part of the wash system and sold together, the claims themselves do not recite anything about the dryers or additional components.

In denying JMOL, the district court analyzed the damage award under the apportionment standards of Panduit Corp. v. Stahlin Bros. Fibre Works, Inc., 575 F.2d 1152 (6th Cir. 1978). The judge concluded that the patentee Belanger sufficiently accounted for apportionment of lost profits between patented and unpatented features by satisfying the Panduit factors. I.e., the jury had enough evidence to reach its decision. On appeal though, the Federal Circuit shifted focus — holding that the non-patented features required a convoy analysis under Rite-Hite Corp. v. Kelley Co., 56 F.3d 1538 (Fed. Cir. 1995). Ultimately, the court issued a remittitur — ordering the district court to shrink the ultimate award.

The critical distinction between apportionment and convoyed sales, overlooked by the district court, was explained by the Federal Circuit in a footnote.

The district court incorrectly viewed Wash World’s motion as presenting an issue of apportionment rather than as one of convoyed sales. Apportionment, and more generally the Panduit factors, apply “when a patentee is seeking lost profits for a device covered by the patent in suit.” Rite-Hite Corp. v. Kelley Co., 56 F.3d 1538 (Fed. Cir. 1995); see also Panduit Corp. v. Stahlin Bros. Fibre Works, Inc., 575 F.2d 1152 (6th Cir. 1978). Where, as here, the issue is incremental damages for portions of products not covered by the patent, the proper inquiry is whether the unpatented components are convoyed sales.

Patent owners seeking lost profit damages face significant hurdles. The Sixth Circuit decision in Panduit v. Stahlin Bros remains the seminal with its four-factor test for proving entitlement to lost profits. Under Panduit, a patentee must establish:

- Demand for the patented product,

- Absence of acceptable, non-infringing alternatives to the patented product,

- Manufacturing and marketing capability to exploit the demand for the patented product, and

- That the patentee would have made a profit if it had made the infringer’s sales.

Beyond damages for the patented product itself, patentees sometimes seek lost profits on “convoyed sales”—unpatented components or products sold alongside the patented item. The Federal Circuit’s landmark decision in Rite-Hite Corp. v. Kelley Co., 56 F.3d 1538 (Fed. Cir. 1995), established the requirements for such damages. Under Rite-Hite, proving lost profits for convoyed sales require a showing that the unpatented and patented products together constitute a “functional unit,” meaning they are “analogous to components of a single assembly or . . . parts of a complete machine.” Convoyed sales damages are not available in situations when items are sold without any functional relationship to the patented invention – even if done for relevant business purposes.

In Wash World, the Federal Circuit determined that Belanger failed to establish the necessary functional relationship between its patented car wash system and the unpatented components (primarily dryers) for which it sought damages. The primary evidence Belanger presented was testimony that approximately three-quarters of customers purchased the patented car wash systems with unpatented dryers already installed, and that these components were typically sold as an “entire system” or “package.” But, at least according to the court, the patentee did not present evidence of how the components functionally interacted or depended on each other.

But I imagine that it is general knowledge among jurors that an automatic car wash system has dryers. And both the General Manager and Technical Expert testified that system sales generally include the entire system (washer + dryer). Dryers are part of the “basics of a carwash” a “must have” feature and “not some add-on.” And here, the jury was instructed that “to recover lost profits for such collateral sales, Belanger must prove . . . the collateral products function together with the patented product as a functional unit.”

The patentee argues this was sufficient and an easy case — just like it would be in a pickup truck analogy:

Just like the V6 engine is part of the pickup truck, these car wash components are functionally part of the claimed car wash system.

But, the brief doesn’t provide detailed technical explanations of functional interdependence between components – instead it focuses on how these components are sold and used together as a complete system. And, the Federal Circuit found these insufficient as a matter of law to support the jury verdict.

Apportionment vs. Convoyed Sales: Distinct Damages Concepts

The Wash World decision underscores a fundamental distinction between apportionment and convoyed sales. Apportionment applies when a multi-component product includes both patented and unpatented features, requiring that damages reflect only the value attributable to the patented elements. As the Federal Circuit has previously held, damages “must reflect the value attributable to the infringing features of the product, and no more.” Commonwealth Sci. & Indus. Research Org. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., 809 F.3d 1295 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

The need for apportionment can be satisfied through proper application of the Panduit factors discussed above. Notably, at times the entire market value of a product can be used as the basis for damages, even lost profits from the entire product, if the patentee shows that the patented aspects are the driver of the sales or profits. Convoyed sales, by contrast typically involve separate products that not covered by the patent claims. And, typically there is a separate price attached to the convoyed products. But the threshold for requiring convoy analysis is quite fuzzy, and the court here does not do a good job of defining that threshold.

In looking through this case, I see a couple of ways the case could have pretty easily turned out better for the patentee:

- Patent drafting: Patentees would obviously prefer to avoid the additional convoy analysis. When patenting new features of a larger system, it often will make sense to include a claim that broadly covers major aspects of the system in addition to the specific novel feature. This is a claim drafting trick, but appears to operationally ensure that the entire system will be considered “infringing.” Michael Risch, A Unified Theory of Convoy Goods, 60 Jurimetrics J. 403 (2020)

- Expert Testimony: The expert testimony for the patentee appears to be what lost the case. The patentee should have presented specific evidence showing that the dryers were functional aspects of a carwash system – part of a single unit that is ordinarily sold together. The expert then should have conducted a better analysis to show the % of the dryer sales that could be considered convoy sales. The key issue that needs to be shown here “whether and how many convoy goods would have been sold in the absence of the infringement.”