by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit in IGT v. Zynga Inc. affirmed the PTAB IPR final written decision finding patent claims obvious. In addition, the court refused another institution challenge — holding that the Agency’s use of “interference estoppel” is an aspect of institution decisions that are generally non-reviewable on appeal. This decision reinforces my belief that the pending SAP and Motorola petitions will be denied.

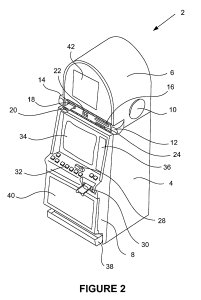

To understand this case, we need to step back to 2003, when patent interference practice still governed priority disputes between competing inventors. IGT owned U.S. Patent No. 7,168,089 for gaming software authorization systems. When Zynga’s predecessor copied IGT’s published claims into its own application, the USPTO declared an interference in 2010. Zynga moved for judgment that IGT’s patent was obvious over certain prior art references (Carlson, Wells, and Alcorn). Ultimately, the Board terminated the interference based upon a finding that Zynga’s application lacked adequate written description support for IGT’s claims.

Fast-forward to 2021: IGT sued Zynga for infringement, and Zynga filed an inter partes review petition challenging the same patent claims. However, Zynga’s IPR relied on different prior art (Goldberg and Olden) that had not been presented during the interference. This created the central question: should interference estoppel bar Zynga from raising new obviousness grounds in the IPR?

The USPTO codified interference estoppel in 37 C.F.R. § 41.127(a)(1), which provides that an interference judgment “disposes of all issues that were, or by motion could have properly been, raised and decided.” IGT argued that since Zynga could have moved on the Goldberg/Olden obviousness grounds during the interference but chose not to, it was now estopped from raising those grounds in any subsequent USPTO proceeding.

The agency’s response involved multiple layers of reasoning. Initially, the Board suggested it would be “unfair” to apply interference estoppel because the interference predated the AIA and was terminated on a threshold issue. The Board also claimed authority to “waive” the interference estoppel rule under 37 C.F.R. § 42.5(b). When IGT sought review, however, Director Vidal provided different reasoning entirely: interference estoppel simply doesn’t apply to IPR proceedings because Part 42 of the CFR (governing IPRs) doesn’t incorporate-by-reference Part 41 (governing interferences).

IGT’s brief methodically dismantled each rationale. The company argued that the Director’s incorporation theory ignored decades of USPTO policy encouraging complete resolution of inter partes disputes in single proceedings. IGT pointed to the rule’s plain language stating that losing parties “may not take action in the Office after the judgment that is inconsistent with that party’s failure to move.” The company also noted that the USPTO had previously applied interference estoppel to IPRs in cases like Adama Makhteshim and Mexichem, creating an arbitrary inconsistency in agency practice.

In oral argument’s IGT’s attorney (and my former law firm colleague) Jennifer Kurcz explained that the interference estoppel is akin to res judicata — claims that are not raised are lost:

Ms. Kurcz: But the theory of interference is that if you’re going to put in jeopardy someone else’s patent, you need to show all your cards. . . . You can’t later go into the office on a new ground and raise yet another attack on patentability.

Rather than focusing on estoppel itself, the Federal Circuit approached IGT’s interference estoppel challenge through the lens of § 314(d)’s unreviewability provision. As Judge Reyna stated during oral arguments:

Judge Reyna: Your argument is going to what I view as merit oriented. But I’m bothered by an even more initial fundamental question that do we even have jurisdiction to hear this case.

That statute makes Director institution decisions “final and nonappealable.” The Judge Taranto opinion found that IGT’s interference estoppel argument fell squarely within § 314(d) because it challenged the agency’s decision to institute the IPR. The court rejected IGT’s attempt to distinguish between statutory and regulatory violations, explaining that § 314(d) contains no such limitation. More significantly, the opinion suggests that substantive legal reasoning (even if incorrect) from the agency doesn’t transform an unreviewable institution decision into something courts can examine. The fact that the USPTO “set forth legal reasoning that is capable of being judicially addressed does not make the unreviewable action reviewable.”

In Cuozzo, the Supreme Court supported general unreviewability of IPR institution decisions. However, that case included a “shenanigans” safety valve, with the Court indicating that certain blatant violations (such as those causing violation of significant constitutional rights) could still be reviewable. This shenanigans principle thus requires at least a quick look at the actual institution decision on appeal – and here the court found reasonable bases for the agency’s position.

New Grounds: Beyond interference estoppel, IGT had also argued that the Board’s obviousness determination was based upon an impermissible new grounds. Zynga’s petition identified Goldberg’s database 28 as the claimed “software authorization agent,” the Board ultimately found that three Goldberg components collectively—database 28, driver 26, and wager accounting module 30—performed the authorization function.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit focused on the substantive concern of notice — and found that IGT itself had cited the driver 26 and wager accounting module 30 in its patent owner response when arguing that Goldberg’s database was merely “ordinary.” This gave IGT notice that the Board might consider these elements in its analysis.

The Federal Circuit is currently considering mandamus petitions in In re SAP and In re Motorola Solutions. Both cases challenge Acting Director Stewart’s rescission of the “Vidal Memo,” which had provided safe harbors against discretionary IPR denials under the Fintiv framework. The petitioners argue that Stewart’s retroactive policy reversal violated due process and the Administrative Procedure Act. The IGT decision provides further evidence that these mandamus petitions are unlikely to be granted. The Federal Circuit’s analysis in IGT includes a strong deference to agency institution actions, even ones that are not well reasoned and are arguably inconsistent.

Jennifer Kurcz (BakerHostetler) argued for the patentee IGT; Elizabeth Moulton (Orrick) for Zynga. Judges Prost, Reyna, and Taranto.

Did someone say shenanigans?

linguistic whimsy: The term “shenanigans” appears uniquely American — first entering the culture in the mid 1800s in California during the Gold Rush.

This is a Fed. Cir. sustaining of an IPR invalidity decision, in an IPR that was already declared and decided. The dispute was over interference estoppel. This is not a due process issue over retroactive rejection of an IPR declaration in which the defendant had alrady Solera-surrended defenses in the subject lawsuit. Nor is it part of an increasingly apparent scheme to prevent most IPRs in general, with various strange rationales.

If your point is that it is possible to distinguish this case from SAP or Motorola, sure, it is possible. That does not mean that it is likely that the CAFC actually will make these distinctions. I think that Prof. Crouch is correct that the CAFC is likely to regard these matters as outside their jurisdiction to review, even on mandamus.