by Dennis Crouch

In Focus Products Group International, LLC v. Kartri Sales Co., Inc., No. 2023-1446 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 30, 2025), the Federal Circuit reversed patent infringement findings against one defendant (Marquis Mills) while affirming most findings against another (Kartri Sales).

The most important part of the decision for patent prosecutors focuses on examiner driven restriction practice and how that can be used to define claim scope. The case also delves into trademark and trade dress issues that I leave for a separate post.

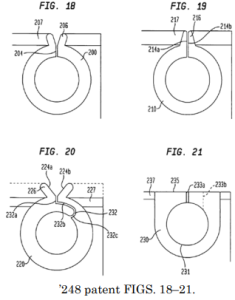

The patents at issue—U.S. Patent Nos. 6,494,248, 7,296,609, and 8,235,088—cover “hookless” shower curtains that attach directly to a shower rod through reinforced ring openings with slits. This integrated approach eliminates the need for separate hooks or clips. The representative claims recite shower rings with specific design features: a slit extending through the ring to an opening, and in some claims, a “projecting edge” that extends from the ring’s outer circumference. The accused products, manufactured by Marquis and sold by Kartri under the “Ezy-Hang” brand, featured rings with flat upper edges similar to Fig 21 above —a design feature that became the central battleground for determining infringement.

During prosecution of the ‘248 patent application, the examiner issued a restriction requirement identifying multiple patentably distinct species and defined those species through specific figure groups. Critically, the examiner distinguished “Species IV” (Figures 18-20, depicting rings with projecting fingers or extensions) from “Species V” (Figure 21, depicting rings “with a flat upper edge”). The patentee elected to pursue Species IV without objection – i.e., election without traversal. The patentee then rewrote the claims in a way that no longer focused on the flat upper edge. Except that one such claim slipped in — the patentee had added re-added a dependent claim that expressly “includes a flat upper edge” and the examiner asked it to be withdrawn as a non-elected species. Finally, in the notice of allowance, the examiner indicated that the non-elected claims had been cancelled as “drawn to a non-elected species without traverse;” and the applicant did no object to that characterization or seek reconsideration.

Eventually the Species IV patents issued without any claims focusing on the flat-upper-edge. However, the claim language was broad enough to encompass versions with both curved uppers and flat uppers. The question in the case then is whether the restriction procedure serves as an affirmative disclaimer of the flat upper scope.

Restriction Requirements in Patent Prosecution When a patent application claims multiple distinct inventions, the USPTO examiner may issue a restriction requirement under 35 U.S.C. § 121, forcing the applicant to elect one invention for examination. The applicant may (with an added fee) pursue non-elected inventions through divisional applications filed before the parent patent issues. Section 121 provides a significant benefit: it protects properly filed divisional applications from double patenting rejections based on the parent patent, eliminating the need for terminal disclaimers that would otherwise tie the patents' terms together and require common ownership. However, this safe harbor applies only if the applicant maintains "consonance"—meaning the divisional claims must respect the boundary lines between the distinct inventions identified in the restriction requirement. As the Federal Circuit explained, "new or amended claims in a divisional application are entitled to the benefit of Sec. 121 if the claims do not cross the line of demarcation drawn around the invention elected in the restriction requirement." Symbol Technologies, Inc. v. Opticon, Inc., 935 F.2d 1569 (Fed. Cir. 1991). If that line is crossed, the § 121 safe harbor is lost and obviousness-type double patenting rejections may be made. Gerber Garment Technology, Inc. v. Lectra Systems, Inc., 916 F.2d 683 (Fed. Cir. 1990).

To be clear, the issued claims don’t say anything one way or the other about whether they cover a flat-upper-edge ring. So, under traditional comprising scope the claims should be interpreted to cover both flat and curved upper-edges. Here, however, the Federal Circuit ruled that the patentee’s election of Species IV without traversing the examiner’s species definitions, combined with the patentee’s acquiescence to the examiner’s withdrawal of claims covering flat-upper-edge rings, constituted a clear and unmistakable disclaimer of that claim scope—thereby excluding flat-upper-edge rings from the claim scope despite the absence of any explicit exclusionary language in the issued claims themselves.

[B]y cooperating with the examiner’s repeated demand to exclude rings with a flat upper edge from the ‘248 and ‘609 patents, in keeping with the initial restriction requirement, the patent owner made it clear that it accepted the narrowed claim scope for these patents.

Disclaimer is often difficult to prove because it must be “clear and unmistakable.” Here, the court found that election without traversal and other compliance with the restriction requirement was sufficient.

The patentee argued this was unfair, the USPTO never argued that flat-top rings were unpatentable – just that the additional claim element created a patentably distinct species. And, election of a species does not equal surrender. Focus also argued ambiguity—that the examiner grouped species by figure reference without a full structural explanation. The panel rejected that reading because the record, taken as a whole, showed the examiner consistently treating a flat upper edge as the nonelected species and the applicant accepting that demarcation.

But, the panel rejected these arguments and the key case on point, Plantronics, Inc. v. Aliph, Inc., 724 F.3d 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2013). In Plantronics, a patentee’s election in response to an ambiguous restriction was not a basis for narrowing the claims vis disclaimer. In that case, the court found ambiguity because the examiner did not provide an explanation of what structural differences distinguished these species from each other. In contrast to Focus Products, where the examiner explicitly identified the flat upper edge as a boundary marker between species and the patentee acquiesced to the examiner’s policing of that boundary.

The prosecution history of the ‘088 patent—a later-filed continuation—reinforced this understanding. During ‘088 prosecution, the examiner rejected all claims for obviousness-type double patenting over the ‘248 and ‘609 patents. The patentee amended the claims to add, among other limitations, a ring with “a flat upper edge,” thereby distinguishing the ‘088 claims from the prior patents. The examiner then withdrew the double patenting rejection, explicitly stating that “the flat upper edge” feature “is drawn to a species which is not encompassed with the species as set forth in the applicant’s prior patents.” When the patentee accepted this characterization and continued prosecuting, it acknowledged the narrowed scope of the ‘248 and ‘609 patents.

What we have here is an important and sometimes overlooked point: prosecution history disclaimer can arise not merely from explicit disavowal statements by applicants, but from a pattern of acquiescence to examiner-imposed boundaries, particularly when the applicant repeatedly declines opportunities to challenge the examiner’s interpretation.

I have to say that I struggle with this decision, but the takeaway has to be to add traversal to your election of species. Here, a simple disagreement even without explanation may have been sufficient, but it may be fruitful going forward to create some standard language such as the following:

While electing the species identified by the Examiner, Applicant notes the potential for overlap of claim scope between the elected and non-elected figures. Applicant does not intend to disclaim coverage of features that may be common to both species.

Divergent Outcomes and Appellate Waiver: The Federal Circuit’s opinion also has an important disparity of outcomes between co-defendants based on appellate waiver doctrine. Both Marquis and Kartri are selling the same products. However, with respect to one of the patents (the ‘088 patent), the court vacated the infringement finding against Marquis (remanding for proper analysis) but affirmed infringement against Kartri.

This divergence stems not from any factual distinction between the defendants’ products—both parties conceded that the accused products contain only rings with flat upper edges—but from differences in how thoroughly each defendant briefed the issues on appeal. Kartri and Marquis filed separate opening briefs that divided issues between them, with Kartri focusing on trademark issues and Marquis concentrating on patent issues with mutual incorporation of arguments by reference. After the Federal Circuit struck these briefs as noncompliant and ordered corrected filings, both defendants insisted their briefs were self-contained and accepted the risk of waiving underdeveloped arguments.

The court found that Kartri’s patent arguments occupied less than one page and consisted primarily of conclusory statements and string citations to the joint appendix without explanation. Kartri thus waived its patent non-infringement arguments. By contrast, Marquis preserved its arguments through more developed briefing on the ‘088 patent’s claim construction and infringement issues. The practical result is that Marquis currently faces no patent liability while Kartri remains liable for infringement.