by Dennis Crouch

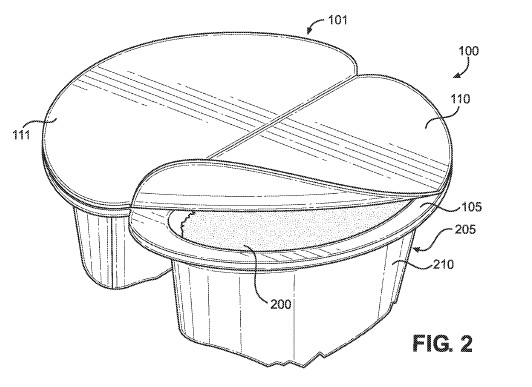

The Federal Circuit affirmed a PTAB obviousness rejection in In re Blue Buffalo Enterprises, Inc., No. 2024-1611 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 14, 2026), holding that the claim terms "configured to" and "configured for" mean "capable of" performing the recited function absent specification language suggesting a narrower construction. The nonprecedential decision, authored by Chief Judge Moore and joined by Judge Taranto and visiting District Judge Chun, rejected the applicant's argument that "configured to" should be construed as "specifically designed to" perform the claimed function. Blue Buffalo's application claimed a wet pet food packaging container with deformable sidewalls and an integrated tool portion for tenderizing food. The claim recited sidewalls "configured to be readily deformable" and the integrated tool having projections "configured for use in breaking up and/or tenderizing the food product." The Board construed both phrases as requiring only that the structures be capable of performing these functions, which allowed the Coleman prior art reference to anticipate the limitations. Blue Buffalo conceded at oral argument that it was not challenging the obviousness determination under the "capable of" construction, effectively staking its entire appeal on claim construction.

The case arrives at an apt moment to note that the law surrounding "configured to" claim language has become something of a dog's breakfast. Over the past two decades, prosecutors have increasingly deployed "configured to" as an alternative to means-plus-function language under 35 U.S.C. § 112(f), hoping to capture functional aspects of an invention without limiting claims to the structures disclosed in the specification and their equivalents. The appeal of "configured to" is that it sounds structural while still defining the invention by its functional results. But this strategy carries real risk. In addition to the categorization in this case, the court could have instead found that the language invokes § 112(f) after all.

At oral argument, Chief Judge Moore cut to the heart of the matter with a question that frames the entire dispute. After Blue Buffalo's counsel argued that "configured to" should mean "specifically designed to," Judge Moore responded:

My concern at a high level is that you're taking a product claim that has to have structural limitations and you're infusing an intent element. Intent. That the person had to design this structure with this intent in mind, as opposed to: we designed this structure without that intent, but it happens to actually do that. I feel like that's good enough because it's a product claim.

Oral Arg. at 3:06 (Chief Judge Moore). Judge Taranto pressed the point further, asking whether "configured to" could become "magic words added anywhere to have the effect that you're talking about, to add this intent element." Oral Arg. at 6:40. Judge Taranto followed up with the key problem of adding an intent element into a product claim:

You [would] have to identify either the ... defendant's designer or manufacturer, and what that entity or person was thinking about when creating this particular structure.

Oral Arg. at 7:44 (Judge Taranto).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.