by Dennis Crouch

For the past year, the Federal Circuit has been systematically tightening the screws on patent damages and particularly pro-patentee expert testimony on the issue. Beginning with EcoFactor, Inc. v. Google LLC, 137 F.4th 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2025), the court vacated a $20 million reasonable royalty award for insufficient apportionment. Then came Jiaxing Super Lighting Electric Appliance Co. v. CH Lighting Technology Co., 146 F.4th 1098 (Fed. Cir. 2025), where the court vacated another award and suggested (in dicta) that experts must quantify their Georgia-Pacific adjustments. LabCorp v. Qiagen reversed a jury verdict on similar grounds. Coda Development v. Goodyear Tire "deflated" a $64 million award for inadequate apportionment. See Dennis Crouch, The Remedies Remedy is Almost Complete: EcoFactor v. Google, Patently-O (May 22, 2025); Dennis Crouch, Federal Circuit Extends EcoFactor Framework to Patent Damages Apportionment in Jiaxing Decision, Patently-O (Aug. 1, 2025); Dennis Crouch, Verdict Deflated: Fed Circuit Punctures Coda's $64M Win Over Goodyear, Patently-O (Dec. 8, 2025). The cumulative message to patentees seemed pretty clear: jury verdicts on damages face appellate scrutiny, and experts who failed to satisfy the court's increasing expectations would have their testimony excluded and the resulting awards overturned.

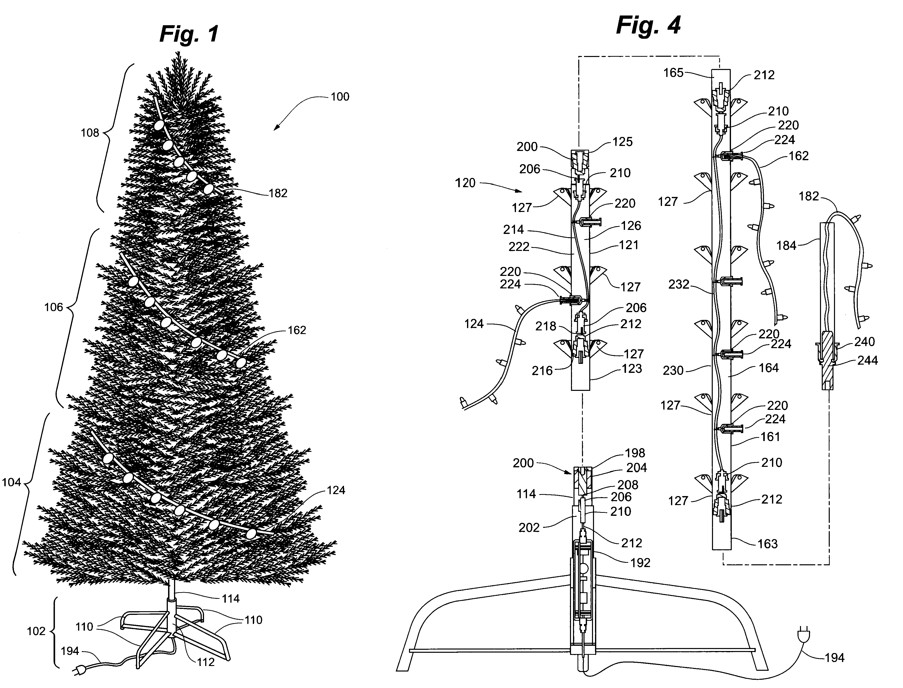

Today's decision in Willis Electric Co., Ltd. v. Polygroup Ltd., No. 2024-2118 (Fed. Cir. Feb. 17, 2026), suggests there is a limit. Writing for a unanimous panel, Chief Judge Moore affirmed a jury's $40+ million reasonable royalty award on a single dependent claim covering coaxial barrel connectors used in pre-lit artificial Christmas trees. The opinion runs to 37 pages, with the bulk devoted to a comprehensive defense of the damages verdict under Rule 702 and Daubert. The court upheld every challenged aspect of the patentee's expert testimony: her income-based apportionment, her market-based apportionment using comparable licenses, and her qualitative application of the Georgia-Pacific factors. Where EcoFactor drew a line against expert testimony predicated on inaccurate factual premises, Willis Electric draws a line in the other direction. It holds that methodological choices about how to model profitability, which licenses to consider comparable, and how to weigh qualitative factors are matters for cross-examination and jury deliberation, not judicial exclusion. The repeated refrain of the opinion is that reasonable royalty calculations "necessarily involve an element of approximation and uncertainty," EcoFactor, 137 F.4th at 1340, and Rule 702 must accommodate that reality.

For many years, I have seen the reasonable royalty "calculation" as a form of speculative science fiction. It is filled with such uncertainty that attempts for mathematical precision simply mask what is fundamentally a rough estimation exercise. The hypothetical negotiation is a legal fiction built on counterfactual assumptions, and the Georgia-Pacific factors provide structure without providing answers. Courts and experts have long struggled with how much rigor to demand from an inherently imprecise inquiry.

In Willis Electric, Chief Judge Moore engages with that tension directly, and several passages seem destined for heavy citation in future damages disputes. The court's core distinction is between (1) an expert who builds on erroneous factual premises -- ones that are "contrary to a critical fact upon which the expert relied" (the EcoFactor problem, warranting exclusion) and (2) an expert whose methodological choices reflect a "fact [dispute] over which reasonable minds can differ" (the Willis Electric situation, left to the jury). The opinion also deploys EcoFactor's own language about "approximation and uncertainty" as a shield rather than a sword, embedding it within a historical survey of reasonable royalty doctrine stretching back to Dowagiac Manufacturing Co. v. Minnesota Moline Plow Co., 235 U.S. 641 (1915), and even a 1960 Columbia Law Review student note. Recovery in Patent Infringement Suits, 60 Colum. L. Rev. 840 (1960).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.