Tag Archives: First to Invent

BlackBerry Case Makes Major Precedential Changes

CAFC Narrows Experimentation Defense to the On Sale Bar

Ex-Post Figures Allowed in Hypothetical Royalty Calculation

Blade Wars: Gillette Wins Latest Round in Multi-Blade Razor Patent Litigation

Gillette’s patent disclosing a three-blade razor also covers a four-blade version.

Gillette Co. v. Energizer Holdings Co. (Fed. Cir. 2005).

By Baltazar Gomez

Gillette owns U.S. Patent No. 6,212,777 for wet-shave safety razors with multiple blades. Gillette sued Energizer in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts alleging Energizer’s QUATTRO®, a four-bladed wet-shave safety razor, infringed claims of the patent. The district court denied Gillette’s motion for a preliminary injunction because it found that the claims covered only a three-bladed razor. On appeal, CAFC vacated the district court’s decision and remanded for further proceeding.

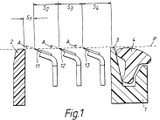

The ’777 patent claims a disposable safety razor with a group of blades, each blade placed in a particular geometric position relative to the other blades. Claim 1 describes a progressive blade exposure as follows:

A safety razor blade unit comprising a guard, a cap, and a group of first, second, and third blades with parallel sharpened edges located between the guard and cap… (emphasis added).

In determining the meaning and the scope of claim 1, the CAFC attempted to place the claim language in its proper technological and temporal context. The Court reasoned that the inventors’ statutorily-required written description in the patent itself, including the claims, the specification and the prosecution history, is the primary source of the meaning of disputed claim language.

Using this standard, CAFC determined that the language “comprising . . . a group of first, second, and third blades” can encompass the four-bladed Energizer razors. To begin, CAFC noted that the claim uses “open” claim terms “comprising” and “group of” in addition to other language to encompass subject matter beyond a razor with only three blades. Moreover, although the specification focused on blade units with three blades, the patent also disclosed a plurality of blades showing that the ‘777 patent covers razors with more than three blades. The CAFC further explained that it may be that a four-bladed razor may be less preferred embodiment, but noted that a patentee typically claims broadly enough to cover less preferred embodiments as well as more preferred embodiments, precisely to block competitors from marketing less than optimal versions of the claimed invention.

Further, CAFC also noted that the specification provided further support for interpreting claim 1 to encompass razors with more than three blades. The first sentence of the written description teaches that the invention relates to razors having a plurality of blades. Moreover, the prosecution of patents related to the ’777 patent also supports reading claim 1 as an open claim. Gillette endorsed an open interpretation of “comprising” when it argued to the European Patent Office (EPO) that a virtually identical claim in Gillette’s European counterpart to the ’777 patent would not exclude an arrangement with four or more blades. Accordingly, the CAFC concluded that the district court erred in limiting the claims of the ’777 patent to encompass razors with three blades because no statement in the ‘777 patent excludes a four-bladed razor.

In dissent, Judge Archer argued that claim 1 should not be construed as permitting a group with more than three blades simply because claim 1 contains the open transition term “comprising” in its preamble. Judge Archer concluded that a three-bladed razor is not merely a preferred embodiment of the invention, but is the invention itself, and that the inventors did not regard a blade unit with four blades arranged in the described geometry as their invention.

Note: Dr. Baltazar Gomez is a scientific advisor at MBHB in Chicago. Dr. Gomez obtained his PhD in biochemistry from the University of Texas and researched retrovirology as a PostDoc at Cornell University.

Case Questions Fundamental Questions of Patentability Requirements of Nucleic Acid Molecules

In re Fisher: EST Patentability Redux

By Donald Zuhn, Ph.D. (Patently-O Guest Author).

On Tuesday, May 3, 2005, the Federal Circuit will hear In re Fisher, in which the Court will address the utility requirement for the first time since the Patent Office set forth revised Utility Examination Guidelines in January 2001. Specifically, in Fisher, the issue of patentable utility is being raised with respect to nucleic acid molecules. In commenting on the possible importance of this case, Harold Wegner has described Fisher as having "the potential of being either the single most important pharmaceutical patent case in recent years – or a yawn." Amicus briefs filed by recognized biotech and pharmaceutical companies such as Affymetrix, Eli Lilly, and Genentech in support of the Board’s decision in Ex parte Fisher suggest that it may be the former as opposed to the latter.

The particular controversy presented in Fisher can be traced back as far as 1991, when a group of NIH investigators led by J. Craig Venter sought to protect thousands of DNA sequences corresponding to portions of expressed genes. Venter called these gene fragments expressed sequence tags, or ESTs. Venter’s group sought to protect not only the ESTs themselves, but also the full-length sequences from which the ESTs were derived and the protein products encoded by the full-length sequences, without first determining the biological function of the encoded protein products. In several applications filed on its ESTs, the NIH asserted a number of utilities, including the design of oligonucleotides for use in chromosomal analysis, PCR amplification, and recovering the corresponding full-length gene. After receiving a second rejection on its initial filing, the NIH abruptly abandoned its attempts to protect the ESTs, and withdrew all of its pending EST applications from consideration.

While the withdrawal of these applications temporarily quieted the debate surrounding EST patentability, the Patent Office again stoked the fires of controversy in 1995, when it published new Utility Examination Guidelines. The new Guidelines removed some of the obstacles to EST patenting by only requiring that an applicant assert a utility that was "specific" and "credible." The new Guidelines had thus omitted the requirement that the assertion of utility also be "substantial," as set forth by the Supreme Court in 1966 in Brenner v. Manson. In 1997, the Patent Office further declared that since ESTs were acknowledged to have utility apart from the full-length sequences from which they were derived, an applicant would no longer be prevented from securing protection for an EST by the failure to specify the function of the full-length sequence from which that EST was derived.

The Patent Office reversed course again in 2001 when it published revised Utility Examination Guidelines, reinstating the Brenner substantial utility prong. The revised Guidelines now required that an applicant assert a specific and substantial utility for the claimed invention that would be considered credible by a person of ordinary skill in the art. The Patent Office also issued Revised Interim Utility Guidelines Training Materials, which provided Examples indicating how the revised Guidelines were to be applied to thirteen different types of biochemical subject matter, including ESTs, as well as definitions of the three utility prongs. In particular, the Training Materials defined "specific utility" as utility that is specific to the subject matter claimed, as contrasted with a general utility that would be applicable to the broad class of the invention; "substantial utility" as utility having a "real world" use; and "credible utility" as utility that is believable to a person of ordinary skill in the art based on the totality of evidence and reasoning provided.

In the appeal to be heard Tuesday, appellants Dane Fisher and Raghunath Lalgudi (employees of Monsanto Co., the real party in interest) seek to reverse the Board’s decision affirming the final rejection of a claim directed to five ESTs isolated from maize leaf tissue. The five ESTs constitute only a small portion of the 4,013 sequences that appellants originally claimed and an even smaller portion of the 32,236 sequences that appellants disclosed in their application. Appellants also asserted a number of utilities for the claimed ESTs in their application, including the use of the ESTs to identify polymorphisms (i.e., alternate forms, or alleles, of the claimed sequences), to design oligonucleotide probes or primers for use in isolating DNA sequences from other plants and organisms, and to measure mRNA expression levels in plant cells using microarray technology.

The Board, in Ex parte Fisher, analyzed Brenner and subsequent CCPA and CAFC decisions in In re Kirk, In re Ziegler, In re Jolles, Cross v. Iizuka, and In re Brana, and determined that "[r]ather than setting a de minimis standard, Section 101 requires a utility that is ‘substantial’," or in the words of the Brenner court, "one that provides a specific benefit in currently available form." The Board then examined appellants’ asserted utilities and determined that none of the claimed ESTs provided a specific benefit in its currently available form. In particular, with regard to appellants assertion that the claimed ESTs could be used to measure mRNA expression levels in plant cells using microarray technology, the Board declared that "the asserted utility of the claimed nucleic acid – as one component of an assay for monitoring gene expression – does not satisfy the utility requirement of Section 101."

In briefing the issues before the Federal Circuit, appellants argue that the Board erred in concluding that an EST is "subject to a heightened standard of utility . . . that hinges upon some undefined ‘spectrum’ of knowledge about the function of the gene that corresponds to the EST." Appellants also contend that the Board erred in concluding that the claimed ESTs lack patentable utility "despite the undisputed existence of eight scientifically useful applications for the claimed ESTs and a commercially successful industry built upon the sale and licensing of ESTs corresponding to genes of unknown function, just like those at issue here." In arguing against the Patent Office’s application of a "heightened standard" of utility in this case, appellants note that the Patent Office has set forth "three substantially different constructions of the utility standard over the last decade alone," and that the Board has adopted a test "so ambiguous and impracticable that even the PTO cannot articulate with any reasonable certainty when the claimed ESTs – or any other EST – might be entitled to patent protection." Appellants also contend that the Patent Office has applied the wrong test in determining whether there is an assertion of specific utility, since "the specific utility prong only requires the existence of an identifiable benefit for the claimed invention; it does not require a benefit that is unique to the claimed invention."

The Patent Office, on the other hand, denies that appellants’ ESTs have been subjected to a heightened standard, arguing instead that appellants merely failed to assert a specific and substantial utility for the claimed ESTs that would be considered credible by a person of ordinary skill in the art. In its brief, the Patent Office often focuses on appellants’ failure to satisfy the specific utility prong, arguing, for example, that appellants’ asserted utilities "would apply not only to the over 32,000 ESTs Fisher discloses, and to the over 600,000 ESTs disclosed in Monsanto’s [six] related appeals, but also to any ESTs derived from any organism." In particular, the Patent Office counters appellants’ argument that because each EST only specifically binds to its complement, the specific sequence of each EST makes its use as a probe or primer specific, by stating that "there is no specific reason for using the EST to bind its complement," and therefore, "[t]o the extent that more sequence data could be acquired by using the ESTs as probes, that result would likely be true for any scrap of DNA derived from nature." Finally, in responding to appellants’ assertion that ESTs have a real world value as part of a multi-billion dollar industry, the Patent Office contends that "batches of ESTs of unknown significance are sold for the purpose of finding targets worthy of further development, not because the individual ESTs have any specific currently available benefit."

NOTE: This post was written by patent attorney Donald Zuhn, PhD. Don is a true expert in cutting edge biotech patent law and practices both prosecution and litigation at MBHB LLP in Chicago. (zuhn@mbhb.com). His article "DNA Patentability: Shutting the Door to the Utility Requirement," published in the summer 2001 issue of the John Marshall Law Review, contains a more thorough discussion of the history of the utility requirement, particularly with respect to the patentability of DNA sequences.

CAFC: Licensee must hold all substantial rights under a patent to bring an infringement suit.

Aspex Eyewear v. E’lite Optik (Fed Cir. 2005) (04-1292)(NON PRECEDENTIAL).

by Joseph Herndon

In general, a licensee is not entitled to bring suit in its own name as a patentee, unless the licensee holds all substantial rights under the patent.

Aspex appealed the decision of the District Court stating that Aspex lacked standing to sue as an exclusive licensee for infringement of two patents (one naming Richard Chao as the sole inventor and the second being a CIP of the first with brothers David and Richard Chao as the named inventors).

Aspex entered into a written license agreement with Chic that granted Aspex an exclusive license in the U.S. to any rights Chic had acquired from third parties relating to patents involving magnetic eyewear. Later, Richard Chao granted Chic an exclusive license for two patents.

In September 2000, Aspex sued E’Lite for infringement of the two patents. Chic was not named as a party to the suit. The district court concluded that Aspex lacked standing to sue because Chic did not convey any future-acquired patent rights to Aspex, and thus Aspex was not an exclusive licensee of the asserted patents.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit held that the plain language of the Chic-Aspex Agreement makes it clear that the agreement relates only to patents then-owned by Chic, not future-acquired ones. The court contended that if the parties had intended to include future-acquired patents, it more likely would have stated “is and/or will become the owner,” within the agreement. The court also looked to use of the past tense “LICENSED” in term “LICENSED PATENTS” to suggest which patents were at issue.

The court further iterated that even though the license covered patents “relating to magnetic eyewear for eyeglasses,” a provision which certainly covers the two patents at issue, the specific grant provisions control the scope of the license agreement—not the general subject matter of the license. Thus, the court held Chic did not grant an exclusive license to either of the patents to Aspex, and as such, Aspex lacks standing to sue.

Joseph Herndon is a law clerk and at MBHB and is a registered patent agent. Joe has a stellar background in electrical engineering and will graduate from law school this year. herndon@mbhb.com.