by Dennis Crouch

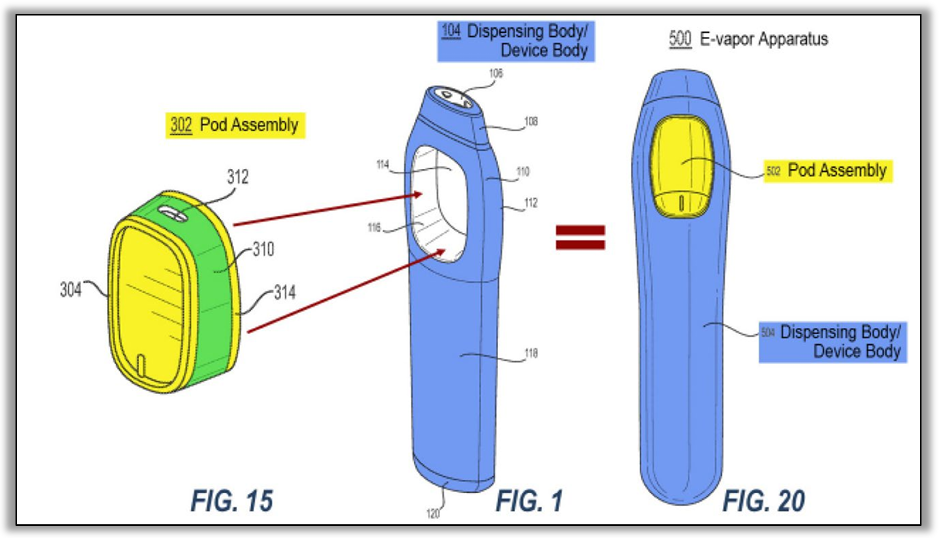

The Federal Circuit's December 19, 2024 decision in Altria (Philip Morris) v. R.J. Reynolds offers important guidance on patent damages methodology while potentially previewing issues soon to be addressed en banc in EcoFactor v. Google. The case centered on Reynolds' VUSE Alto e-cigarette product and its infringement of three Altria patents. U.S. Patent Nos. 10,299,517, 10,485,269, and 10,492,541. While the court addressed multiple issues, I want to focus here on the damages analysis - particularly regarding comparable licenses and apportionment. Although the case is non-precedential, it includes both a majority opinion (authored by Judge Prost and joined by Judge Reyna) and a dissent (by Judge Bryson). Like Judge Reyna's decision in EcoFactor, the case involves the use of lump-sum licenses to create a running royalty calculation, as well as the proper approach to apportioning damages so that the award is for the use of the patented invention.

The damages dispute focused primarily on how Altria's expert derived a 5.25% royalty rate from comparable license agreements, particularly a license between Fontem and Nu Mark. Under this agreement, Nu Mark paid Fontem a $43 million lump sum for rights to practice Fontem's patents through 2030. Following established precedent from Lucent Technologies, Inc. v. Gateway, Inc., 580 F.3d 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2009), Altria's expert analyzed Nu Mark's sales projections to convert this lump-sum payment into an effective royalty rate. The expert identified projections showing that a 5.25% royalty applied to sales from 2017 to 2023 would yield approximately $44 million in payments - close to the actual $43 million lump sum paid.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.