by Dennis Crouch

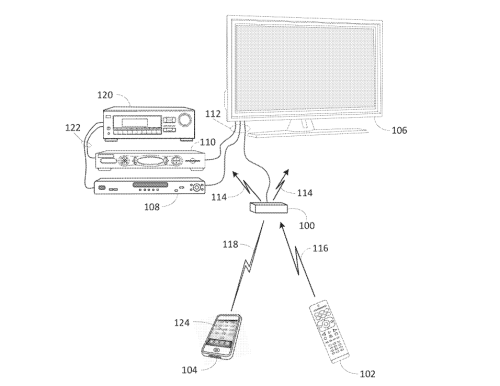

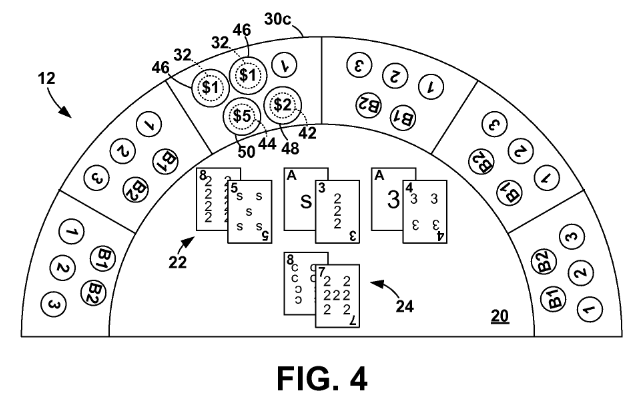

In SmartSky Networks, LLC v. Gogo Business Aviation, LLC, No. 2023-1058 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 31, 2024), the Federal Circuit has affirmed a lower court denial of a preliminary injunction sought by the patentee SmartSky against Gogo. SmartSky sued Gogo in 2022 for patent infringement, alleging that Gogo’s 5G wireless network infringed several of SmartSky’s patents related to in-flight internet wireless connectivity. See U.S. Patent Nos. 9,312,947, 11,223,417, 10,257,717, and 9,730,077. Along with its complaint, SmartSky moved to preliminarily enjoin Gogo from providing its in-flight network. SmartSky argued it had shown a likelihood of success on the merits and that it would suffer irreparable harm without an injunction, but the D.Del. district court Judge Gregory Williams disagreed. A grant or denial of preliminary injunctive relief can be immediately appealed, but the patentee's appeal has also failed.

The preliminary injunction motion was associated with a new 5G network that Gogo had announced in 2019. That network is, according to Gogo, "still in a pre-launch phase." Although customers are not yet actively using the service, the network itself is actually complete and the final step is including the chipsets within the planes. This aspect of the case was the most critical for the Federal Circuit who concluded that the current status of Gogo's operation was not definite enough to create irreparable harm.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.