By Jason Rantanen

It’s time for the annual Federal Circuit statistics update! As I’ve done for the past few years, below I provide some statistics on what the Federal Circuit has been doing over the past year. These charts draw on the Federal Circuit Dataset Project, an open-access dataset that I maintain containing information on all Federal Circuit decisions and docketed appeals. The court’s decisions are collected automatically from its RSS feed, and my research team uses a combination of Python-based algorithmic processing and manual review to code information about each document.

One of my goals with this dataset is to make it publicly accessible so that anyone can use it in their own research. A complete copy of this year’s release is archived at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/CAFC_Dataset_Project, and the codebook is also available there. If you’re a researcher interested in using the dataset, feel free to reach out—I’m happy to help you work with the data or answer questions about it.

On to the data!

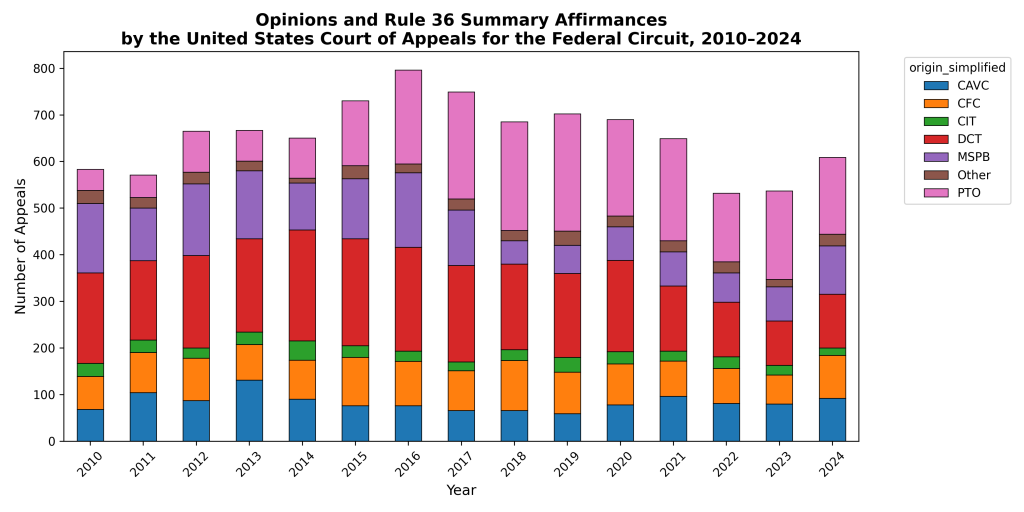

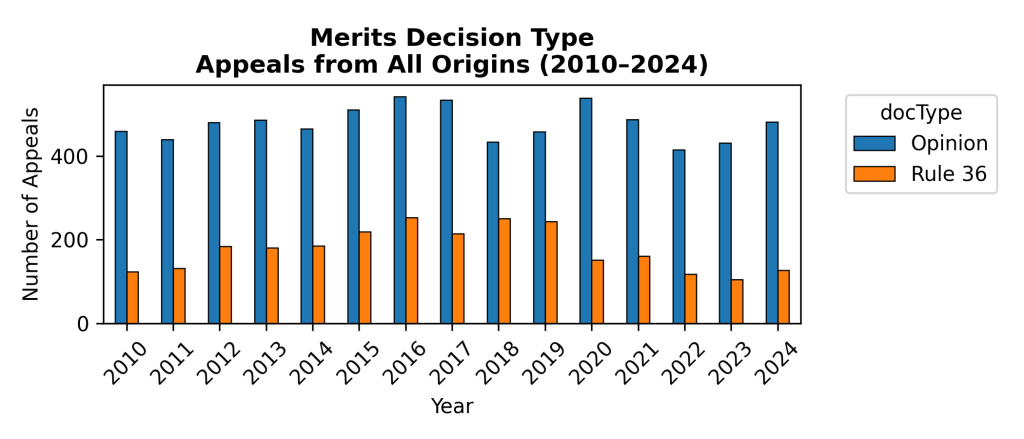

Figure 1 shows the number of Federal Circuit opinions and Rule 36 summary affirmances by origin since 2010. These represent individual documents (i.e., a single opinion or Rule 36) rather than docket numbers (which is how the Federal Circuit reports its own metrics). Overall, about 20% of the Federal Circuit’s merits terminations were issued as Rule 36 summary affirmances.

Opinions vs. Summary Affirmances

For 2024, the overall number of merits decisions increased by about 70 compared to 2023. As in recent years, the highest number of merits decisions arose from the PTO. However, decisions arising from the district courts increased by about 20% in 2024. The court issued 115 merits decisions from the district courts in 2024, up from 95 in 2023 and close to 117 in 2022. In contrast, there was a decline in decisions arising from the PTO—from 190 in 2023 to 165 in 2024.

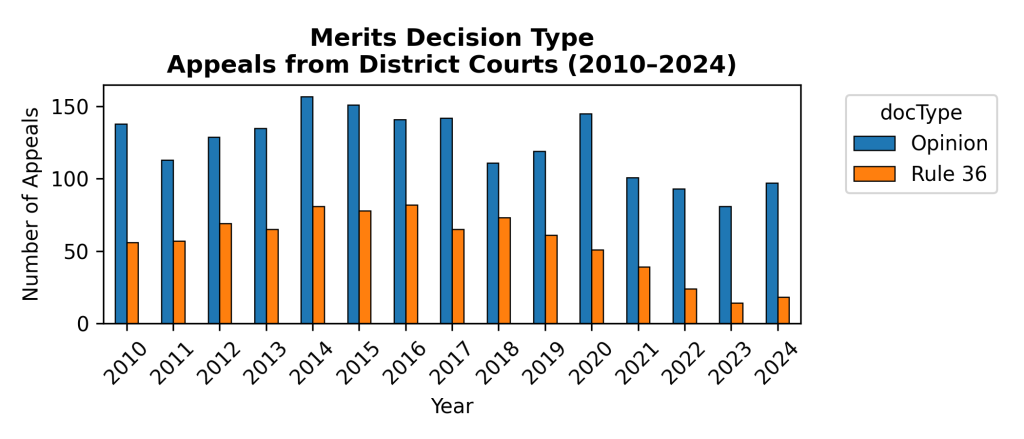

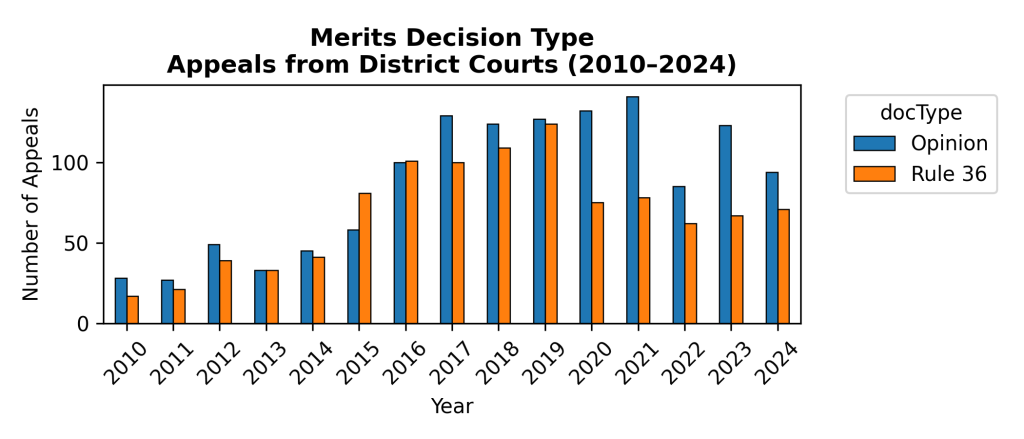

Figures 2a and 2b show the number of opinions versus Rule 36 summary affirmances arising from the district courts and PTO. In 2024, the Federal Circuit continued to issue Rule 36 affirmances fairly often in appeals from the PTO but only rarely in appeals from the district courts. Figure 3 displays the overall frequency of Rule 36 affirmances relative to opinions across all origins.

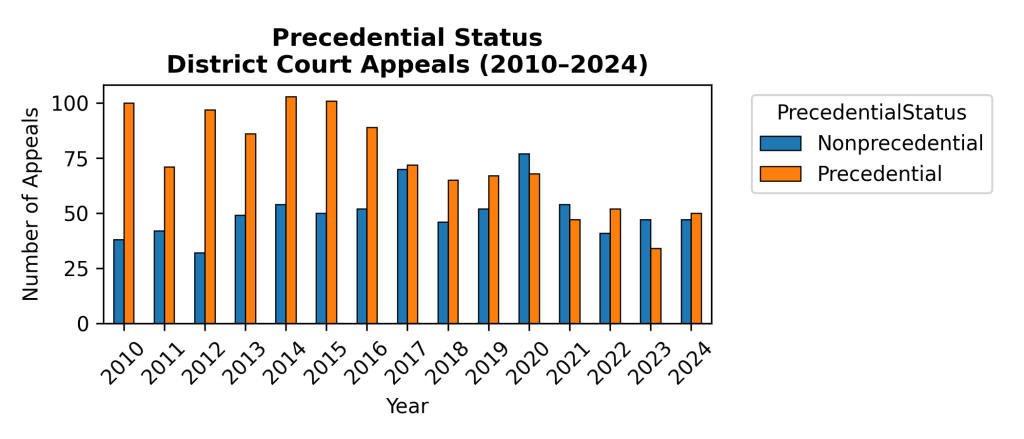

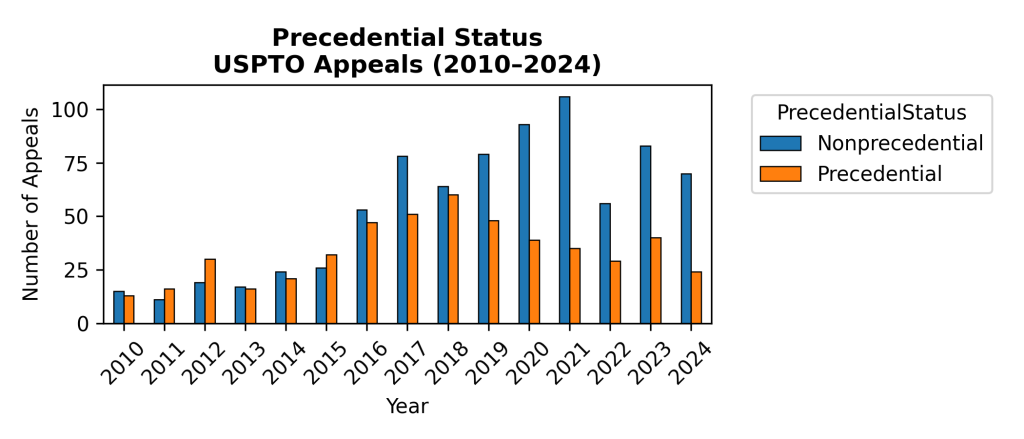

What about the opinions the court is issuing? As shown in Figures 4a and 4b, the court continues to issue nonprecedential opinions regularly in appeals from the district courts, and somewhat less frequently in appeals from the PTO. In other words, the court typically issues an opinion (rather than a Rule 36) in appeals from the district courts, but when it does, it’s just as likely to be nonprecedential as precedential. Conversely, while opinions in PTO appeals are less common, they are more likely to be precedential.

Dispositions

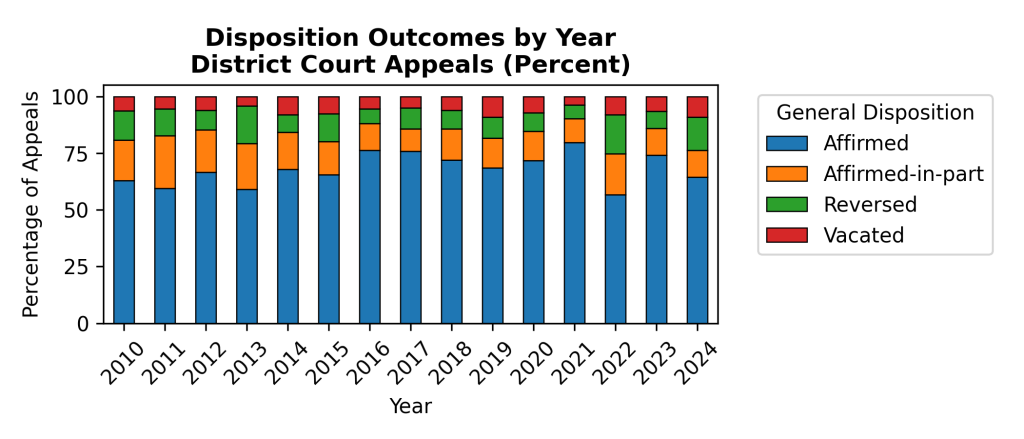

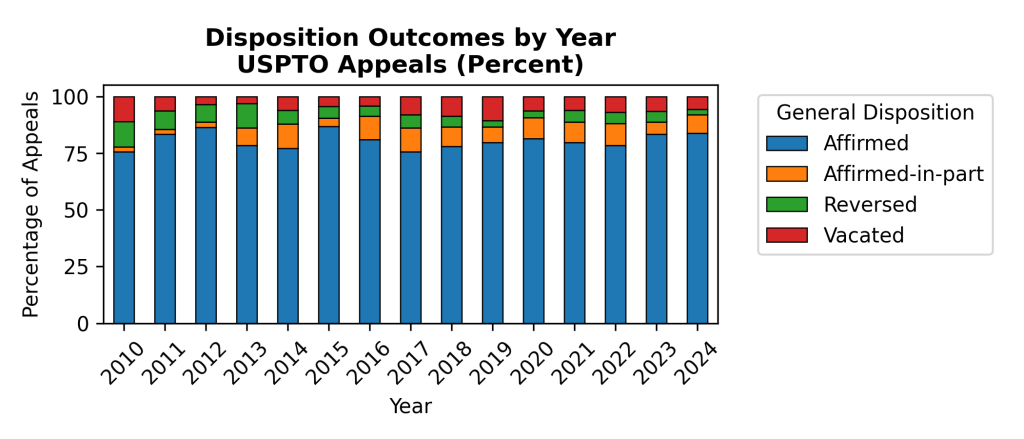

Figure 5 shows the general disposition of Federal Circuit appeals – in other words, whether the panel affirmed, affirmed-in-part, reversed-in-full, etc. Overall, affirmances in appeals from the district courts were a little less frequent last year (65% affirmance in full; 76% affirmance in full or part), while affirmances in appeals from the USPTO continued to be common (84% affirmance in full; 92% affirmance in full or part).

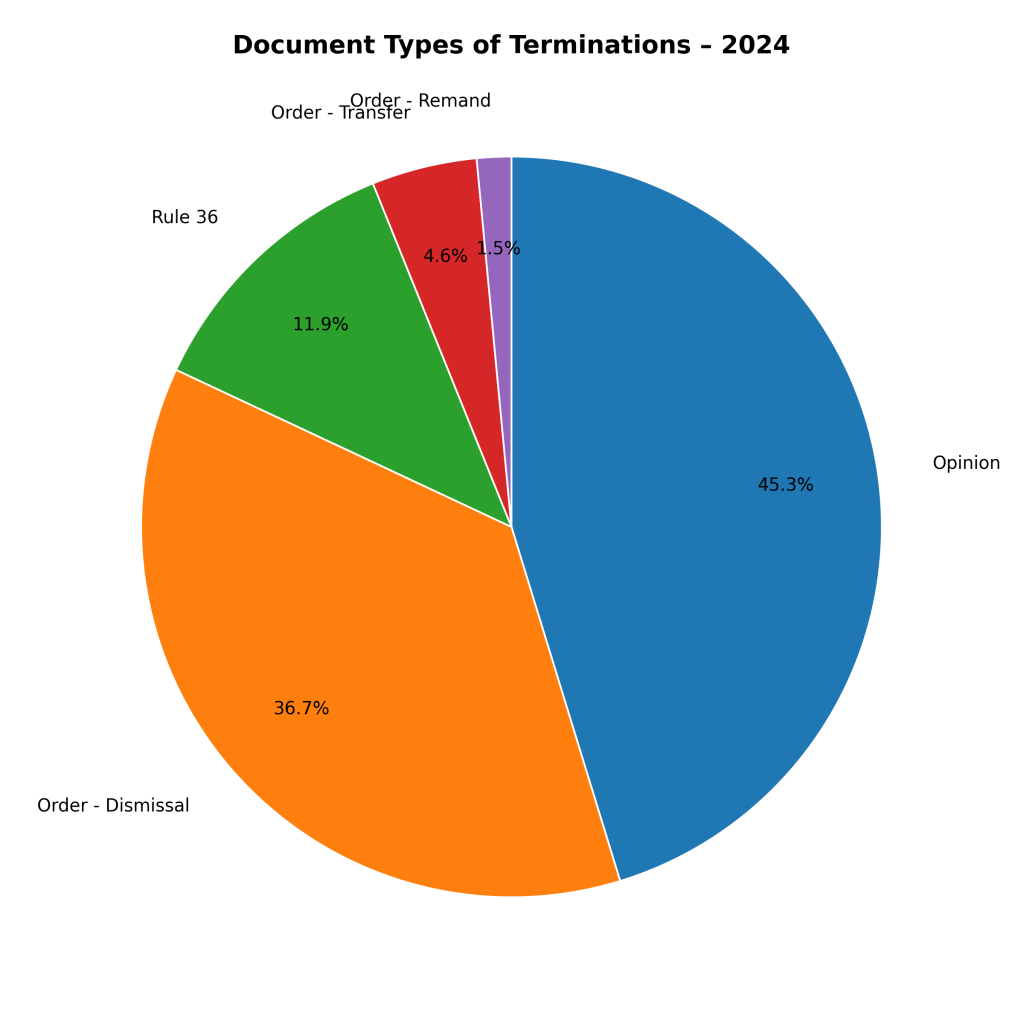

Figure 6 shows the distribution of terminating documents of any type for 2024 regular appeals. About 57% of terminating documents were Opinions or Rule 36 summary affirmances (i.e., merits decisions). Most of the remainder were dismissals (including voluntary dismissals), with a small number of transfers and remands (typically issued through orders). Note that these terminations are counted per document, and appeals dismissed for procedural reasons (such as failure to prosecute) are sometimes later reinstated—so the percentage of appeals ultimately terminated via dismissal is somewhat lower than shown in this figure.

As with the previous figures, the unit of record for Figure 6 is a document—i.e., an opinion or order. A single document, such as an opinion, may decide multiple appeals.

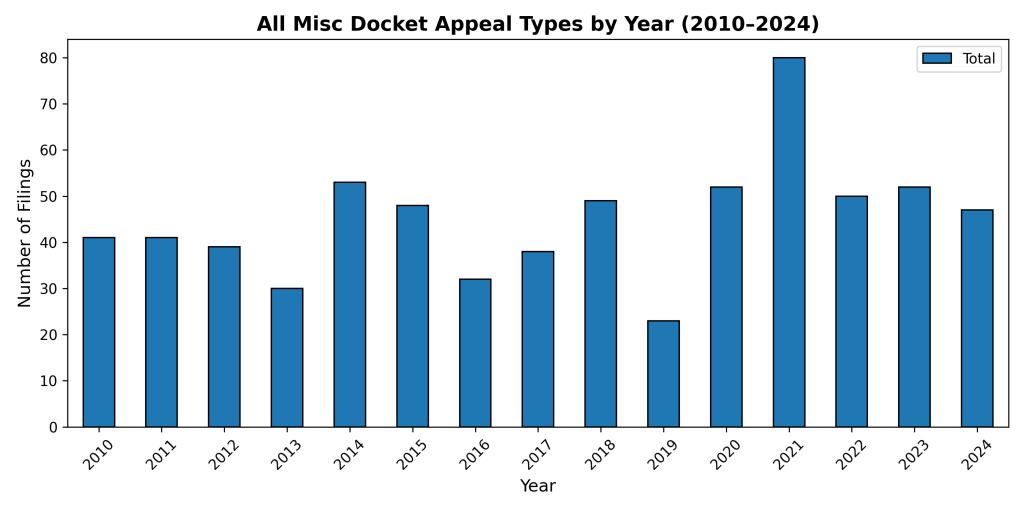

What about petitions for writs of mandamus? These, along with petitions for permission to appeal, are shown below. Figure 7 indicates a slight decrease in the number of decisions on petitions last year. Nearly all (42) of the 2024 decisions on miscellaneous docket matters involved petitions for writs of mandamus.

What were the outcomes of these petitions? Of the 20 decisions on writs of mandamus arising from the district courts in 2024, just one was granted—a substantial shift from recent years.

If you’d like to explore the data yourself, it’s archived on the Harvard Dataverse. I’ve also updated the docket dataset to include appeals filed in 2024. A printout of the Jupyter Notebook used to generate this report is available there, along with an Excel file containing the underlying data tables. If you use the datasets, please cite them as follows:

-

Replication materials for blog post:

Rantanen, Jason, 2023, “Replication Data for ‘Federal Circuit Decisions Stats and Datapack'”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HPARYR, Harvard Dataverse, V6 -

Document dataset:

Rantanen, Jason, 2021, “Federal Circuit Document Dataset”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UQ2SF7, Harvard Dataverse, V7, UNF:6:cbz6tO1MyVSewzIAncqf2A== -

Docket dataset:

Rantanen, Jason, 2021, “Federal Circuit Docket Dataset”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EKSYHL, Harvard Dataverse, V6, UNF:6:io8bOGQ323wHBLZMlUsm+w==