All posts by Jason Rantanen

Guest Post by Prof. Goodman – Unseen Contributors: Rethinking Attribution in Legal Practices for Equity and Inclusion

Guest Post: Diversity Pledge: Boosting Innovation and Competitiveness

Guest Post: Why Do Women Face Challenges in the Patent Process?

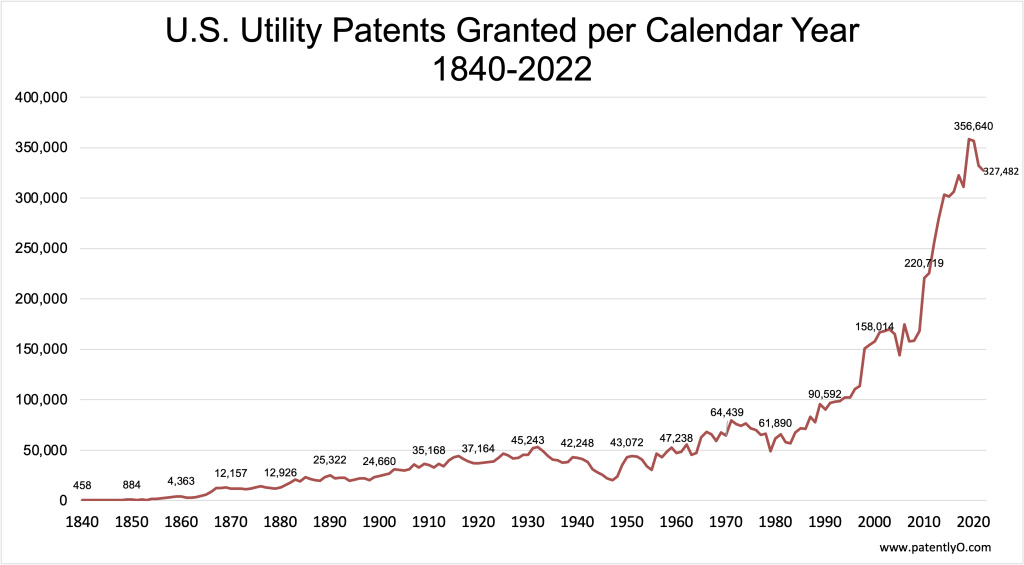

Utility Patents Granted per Calendar Year, 1840-2022

Guest Post by Prof. Koffi: A Gender Gap in Commercializing Scientific Discoveries

Guest Post by Kevin Ahlstrom: Closing the Gender Innovation Gap with Guided Inventor Sessions

Guest post by Prof. Robinson: How We Can Bridge the Innovation Gap

Guest Post: Jillian Grennan, Charting New Paths in Innovation: Reflections from Harvard’s Innovation Economics Conference

Guest Post: Piers Blewett, Bridging the Gap: IP Education for All with SLW Academy

Guest Post: Margo Bagley, The Diversity Pilots Initiative

Guest Post by Profs. Masur & Ouellette: Public Use Without the Public Using

Federal Circuit Dataset & Stats: January 2023 Update

Guest Post by Prof. Hrdy & Dan Brean: The Patent Law Origins of Science Fiction

Guest Post by Prof. Burstein: Design patents: Line drawing & Locarno

By Sarah Burstein, Professor of Law at Suffolk University Law School.

Columbia Sportswear North America, Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., 21-2299 (submitted but not decided) (oral argument recording available here)

The Federal Circuit heard oral arguments yesterday in the second round of Columbia v. Seirus. (Prior Patently-O coverage of this appeal is available here.) My 2015 article, The Patented Design, was mentioned several times during the argument.

In that article, I argued that a design patent’s scope should be limited to the design as applied to a specific type of product. In making that argument, I acknowledged that this approach could create some line-drawing problems, including the type that have arisen in Columbia v. Seirus. I suggested that, with respect to infringement:

[O]ne solution would be to put the burden of proof on the patent owner to show that the accused device should be considered the same type of product. Courts have been tasked with determining which products are and are not the same “type” of product in the trademark context; there is no obvious reason why they should not be able to do the same in the design patent context.

If, however, the line-drawing problem proves to be intractable, an alternative would be to determine product “types” according to the Locarno Agreement Establishing an International Classification for Industrial Designs. Specifically, “type of product” could be defined to map onto Locarno sub-classes. For example, Locarno Class 10 includes subclasses for “Clocks and Alarm Clocks,” “Watches and Wrist Watches,” and “Other Time-Measuring Instruments.” The Locarno classification system is not perfect for this use but it may provide a second-best solution if judicial common law development proves unworkable.

Sarah Burstein, The Patented Design, 83 Tenn. L. Rev. 161, 219–20 (2015) (footnotes omitted). So my argument was not that design patent scope (and in this case, the scope of comparison prior art) must be limited to the exact, specific type of article named expressly in the verbal portion of the design patent claim.

Instead, I argued that courts should look to whether the accused product (or reference) is the same general type of article.

I also suggested that the product type could be determined with reference to Locarno sub-classes. How might that work in practice?

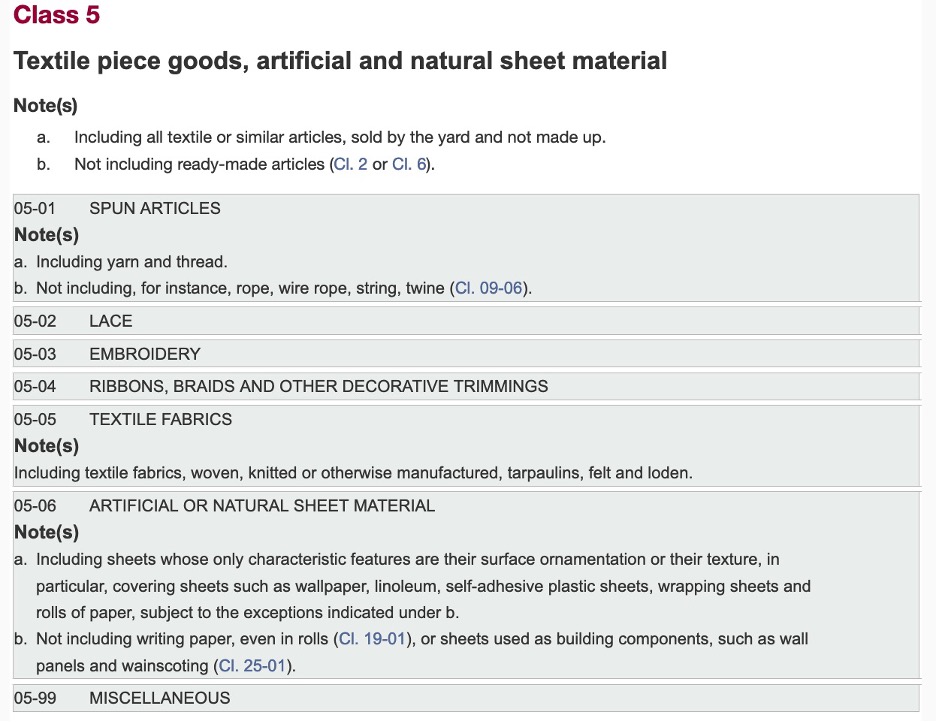

Looking at the dispute in Columbia v. Seirus, the most relevant class would seem to be Class 5, “Textile piece goods, artificial and natural sheet material.” Here are the relevant class subheadings:

So which subclass(es) would apply here? This case is an example of how the “substantial latitude” that design patent applicants are given in describing the relevant article in their claim language, see MPEP § § 1503.01(I), might sometimes complicate later attempts at classification.

The asserted design patent, U.S. Patent No. D657,093, claims “the ornamental design of a heat reflective material.” The only Class 5 subclass heading that uses the word “material” is 05-06, “Artificial or Natural Sheet Material.” But the patented design seems to be directed more to something like the examples mentioned in subclass 05-05, “Textile Fabric.” (Indeed, if you look closer at the full Locarno Classification, subclass 05-05 specifically includes ID No. 100480, “Insulating fabrics.”)

So which bucket would the D’093 fit in best? Where classification is disputed, the burden of persuasion should be on whichever party wants to prove something is the same type of product.

For infringement, then, the patent owner should have to prove the accused product is the same type as what is claimed. For comparison prior art, the accused infringer should have to prove the reference is the proper type. (This is because the use of the prior art in evaluating infringement is a one-way ratchet; it can only be used to narrow the presumptive scope of a claim, not to enlarge it. See Sarah Burstein, Is Design Patent Examination Too Lax?, 33 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 607, 612 (2018).)

Evidence relevant to this inquiry could include information about any commercial embodiments, including information the patent owner has provided to regulators about their product or market. And if a patent owner has registered their design internationally, the design may already have a Locarno sub-class.

Who should decide? Judges would be well-suited to make these types of determinations. Indeed, these issues are likely to arise at the Markman stage or, as in Columbia v. Seirus, in motions in limine. This is not the kind of credibility or historical-facts determination that we normally leave to juries. Indeed, it’s difficult to imagine a way to effectively instruct juries on this issue without injecting undue confusion into the infringement analysis.