by Dennis Crouch

Abraham Lincoln holds a unique distinction as the only U.S. President to hold a patent. U.S. Patent No. 6469, granted in 1849, covered a device for lifting riverboats over shallow waters using bellows and air chambers. Lincoln also litigated patents in his role as a lawyer. His experience with the patent system informed what would become one of the most quoted aphorisms in intellectual property law, delivered during Lincoln’s largely forgettable 1858 lecture on “Discoveries and Inventions.” In that lecture delivered in Bloomington, Illinois, Lincoln declared that the patent system “added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius, in the discovery and production of new and useful things.” IMO, this elegant formulation captured the fundamental economic theory underlying patent law. Humans have natural creativity and genius that is always burning, but the material incentive of exclusive rights is often needed to spur innovation.

Lincoln’s lecture traced the evolution of human innovation from the biblical first human invention (fig leaf clothing) to the Industrial Revolution. He specifically praised the U.S. Constitution’s Patent Clause as itself a “a great step in the progress of civilization.”

I have already intimated my opinion that in the world’s history, certain inventions and discoveries occurred, of peculiar value, on account of their great efficiency in facilitating all other inventions and discoveries. Of these were the arts of writing and of printing — the discovery of America, and the introduction of Patent-laws.

The speech does not delve into contemporaneous decisions such as O’Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. 62 (1854), that raised the concern of overclaiming and monopolizing a broad principle (or abstract idea). However, the “fire” metaphor may have been an intentional inversion of Thomas Jefferson’s earlier fire imagery. In his 1813 letter to Isaac McPherson, Jefferson argued that ideas are “like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point” and thus should spread freely rather than be subject to “exclusive appropriation.” Jefferson’s fire metaphor emphasized the non-rivalrous nature of knowledge – that ideas, like flames, can be shared infinitely without diminishing the original source.

These musings of Lincoln and Jefferson anticipated many themes that would later emerge in economic scholarship on innovation. The “fuel of interest” metaphor captured what modern economists call the incentive function of patents—the idea that exclusive rights provide financial motivation for invention. The “fire of genius” – inherent to humans – acknowledged the creative impulse that serves as a baseline that might be enough to produce socially beneficial innovation even without patent rights. And Jefferson’s notion of freely sharing ideas anticipated what economists recognize as the public-goods nature of knowledge. Lincoln did not delve deeply into the incentive mechanism – noting only that securing the exclusive rights for a limited time provided the inventor a “special advantage.”

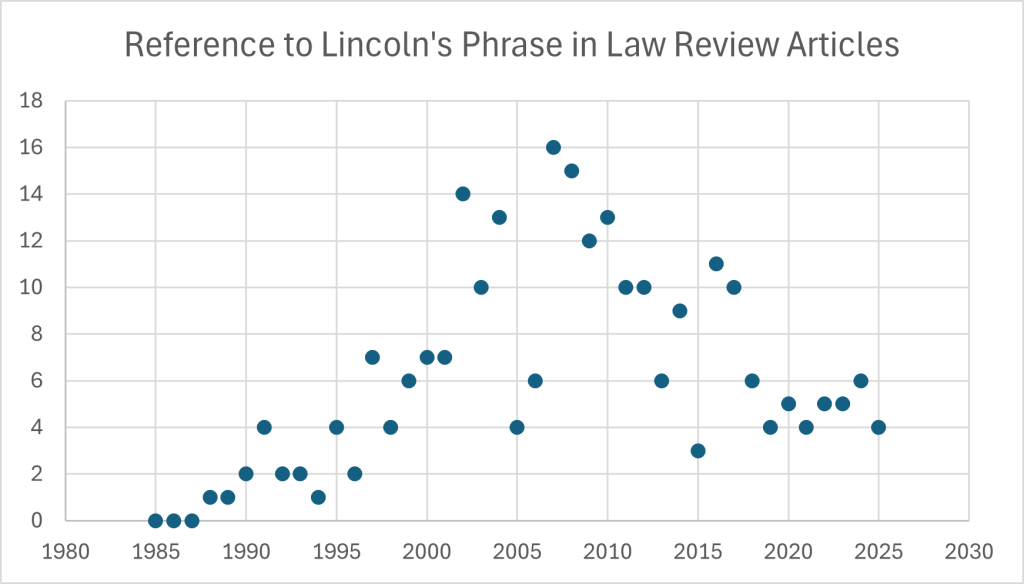

Lincoln’s lecture itself proved unsuccessful on the 1850s speaking circuit. Contemporary accounts described audiences as disappointed, finding Lincoln’s scholarly approach less engaging than his political oratory. Lincoln himself later acknowledged the speech as “a rather poor one,” and he abandoned the lecture circuit after several unsuccessful performances. However, he did keep a copy of the speeches that later found their way into his collected speeches and eventually into popular culture. It was engraved in stone above the Department of Commerce building in 1932 (image above) that housed the USPTO until 1967. And, the aphorism continues to be repeated and considered – at least by those of us working in patent law.

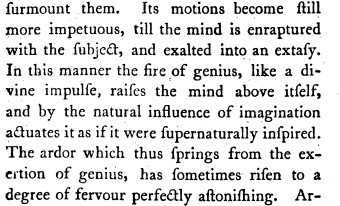

The Pre-Lincoln Roots of “Fire of Genius”

While Lincoln’s formulation has become iconic in patent law the “fire of genius” metaphor had already been part of a literary tradition spanning nearly a century before his 1858 lecture. The earliest documented use that I found was Alexander Gerard’s 1774 “Essay on Genius,” which described how “the fire of genius, like a divine impulse, raises the mind above itself.”

By 1800, the phrase seems to have become well-established in educated discourse, appearing in works by Mary Wollstonecraft, who praised “Rousseau alone, the true Prometheus of sentiment, possessed the fire of genius,” and in John Raithby’s legal writings on oratory. The metaphor was also found in late 1700s French (feu sacré du génie”) and German (“Feuer des Genies”).

Lincoln seems to have been the creator of the idea that patents provide “fuel of interest,” although other writers had talked about various activities adding or dampening the fire of genius. My favorite might be the old Latin proverb: “Vinum ingenii fomes” = “Wine is the fuel of genius.” External stimulants were also looked for by others, including Voltaire who was legendary for his coffee consumption (~40 cups per day) and Freud whose cocaine use fueled his intellectual capabilities. See Sigmond Freud, Über Coca, Centralblatt für die gesammte Therapie 289 (1884).

Though his 1858 lecture failed to captivate contemporary audiences, Lincoln’s formulation that patents add “fuel of interest to the fire of genius” is unlikely to leave us anytime soon.

Thanks for this “big picture” post, contrasting your usual posts that delve into a small sliver of modern patent (and other IP) law. Lincoln’s formulation always seems unclear to me, and I think it is the term “interest” that I stumble upon. In our era, perhaps he would have said “added the fuel of ownership to the fire of genius.”

Thanks B — and I totally get that stumble. I think Lincoln’s use of “interest” can throw us off today because we usually associate the word with curiosity. But I believe that for Lincoln the lawyer in the 1850s, “interest” was understood in the legal and economic sense. Much like we still use it when we talk about a “financial interest” or “conflict of interest.” So Lincoln’s metaphor really boils down to the idea that patents supply the material incentive — the personal stake — that fuels creative effort. Your idea of “ownership” works nicely.