In some technologies where patenting has a long and extensive tradition, the lack of non-patent prior art is not a serious problem. In other areas such as software and biotechnology, non-patent references harbor most of the important prior art.

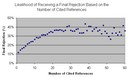

Results: My new study of 100,000 recently issued patents reveals that patent that cited non-patent literature are significantly more likely to receive rejections from the PTO. Specifically, patents citing at least one non-patent reference have a 39% greater chance of receiving a final rejection when compared with patents that issued without citing any non-patent references. Regarding non-final rejections, citing non-patent prior art increased the likelihood of receiving a rejection by 9%.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.