Ron Slusky is back with more insight from his 2007 book Invention Analysis and Claiming: A Patent Lawyer’s Guide (ABA). This fall, Slusky will be hosting a series of two-day claim drafting seminars. See www.sluskyseminars.com. The following are five of Slusky’s “Prescriptions for Drafting Broader Claims.”

1. Define, Don’t Explain

Patent attorneys love to explain things. This is a valuable trait when writing the specification. But it can get in the way when drafting claims. It is hard to resist the urge to liven up a claim’s dull litany of elements by explaining that the claimed subject matter is an automobile floor mat; or an optical system with improved output efficiency…That urge to explain must be resisted nonetheless.

A claim’s function is to define the boundaries of the parcel of intellectual property being sought—not to explain or to help readers to understand something. An explanatory-type limitation may seem harmless enough, but every extra word in a claim is a potential loophole for infringers to exploit.

Limitations should be suspected of explaining rather than defining if they recite:

- The advantage of the invention or what it is “good for;”

- How the recited combination can integrate with the external environment;

- Motivations (e.g., for doing a particular step or including a particular element);

- How to carry out a recited function where the recitation of the function itself imbues the claim with patentability;

- How inputs get generated;

- The source of something that the claimed method or apparatus works on.

A limitation that meets any of these criteria should be scrutinized as a candidate for deletion. If the claim distinguishes over the prior art without the limitation, the claim is probably well rid of it.

2. Scrutinize Every Modifier

Beware the insidious modifier, particularly adjectives. Most of them are unnecessary in a broad claim, serving to explain rather than to define. Each modifier in a claim should be scrutinized to see if the claim will support patentability without it.

Here are some examples: automobile floor mat; very-large-scale integration; high-resolution filter; decoding a transmitted video signal by…; rapidly removable label; block copolymer. (As to the latter, see Phillips Petroleum Co. v. Huntsman Polymers Corp., 157 F.3d 866 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (affirmed summary judgment of non-infringement).)

Another potential problem with certain modifiers is their potential for being declared indefinite. The terms “very-large-scale,” “high-resolution” and “rapidly” in the above examples are problematic in this sense.

3. Assume That Input Signals and Data/Parameter Values Are Already In Hand—Don’t Generate Them in the Claim

A method or apparatus often operates on input signals and/or may use data values, parameters or counts of things. When claiming the broad invention, it is usually desirable to treat such things as already existing rather than explicitly generating them within the claim.

For example, suppose the invention is the idea of adjusting the output rate of a widget-manufacturing process once the number of widgets produced within the previous hour reaches a certain limit. The invention could be defined in two steps—a counting step and an adjusting step:

|

1. A method for use in a machine that manufactures widgets, the method comprising

counting the number of widgets manufactured in an hour’s time, and

adjusting the output rate of said machine when the count reaches a predefined limit.

|

However, it is irrelevant to the inventive concept how the number of widgets manufactured in an hour is determined. Indeed, the potential infringer might use the cumulative weight of an hour’s output to determine how many widgets were produced and, in so doing, avoid a literal infringement of this claim

By assuming that the widget count is already known—handed to us by a genie, perhaps—and available to the adjusting step, the entire counting step can be eliminated:

|

2. A method for use in a machine that manufactures widgets, the method comprising

adjusting the output rate of said machine when the number of widgets manufactured within an hour’s time reaches a predefined limit.

|

4. Write the Claim Out of Your Head, Not Off the Drawing

Looking at the drawings is useful when intermediate- or narrow-scope claims are being drafted since such claims intentionally incorporate certain embodiment details.

However, the drawings may interfere with the conceptual thinking that is so desirable when reaching for breadth. It is all too easy for the drawings to draw our attention away from the abstract, exposing us to the siren song of the embodiment and its tangible details—details that can unduly narrow a claim.

It is much harder to be attracted to embodiment details when they are not staring up at us from the drawing. Thus the broadest claims should be written directly out of the claim drafter’s head. The mind’s eye should be able to so clearly see those few functionalities and interrelationships that define the broad invention as to make it unnecessary to look at the drawings.

If we find ourselves unable to write the claim with the drawings put away, it may be time to stop and re-engage the invention conceptually, returning to the claim drafting only when a crystal-clear answer to the question What is the Invention? is fully in hand.

5. Strive for Simplicity

Simplicity is a key to clarity. Convoluted interrelationships or claim language that is difficult to read through can signal that the invention has not been captured at its essence. Often buried in such a claim are ambiguities or unduly limiting recitations that aren’t necessary to the invention.

The architectural philosophy of form follows function applies here. A claim whose form is clean and simple is more likely to serve the function of defining the invention cleanly and simply (read “broadly”). The hallmark of a well written claim is one that an inventor can understand without a lot of attorney explanation.

Once it becomes apparent that a claim-in-progress is evolving into an awkward mess, it is best to stop and rethink the approach. Often the culprit is that the limitations are introduced in a less-than-optimal order. Indeed, limitations that had seemed so necessary may fall away completely once the claim elements are rearranged. Or certain limitations in the preamble might be better put into the body of the claim or vice versa.

There is little point in fighting a recalcitrant claim. Better to look for some underlying assumption about the claim structure that is getting in the way and to start over. It can be hard to put on the brakes and abandon a claim in which a lot of time has already been invested. It’s good, then, to stay alert to the possibility that things are beginning to deteriorate and to regroup sooner rather than later.

Copyright © 2007-2008 American Bar Association. All rights reserved. Adapted with permission.

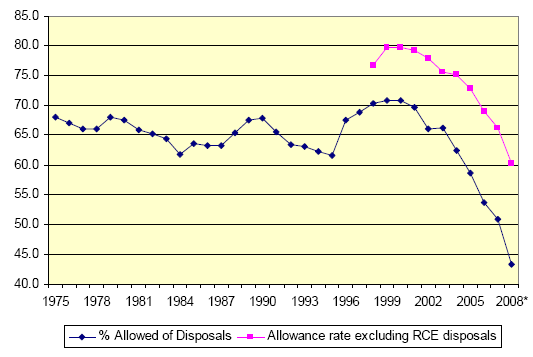

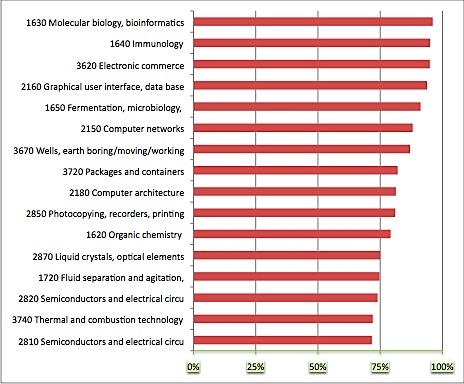

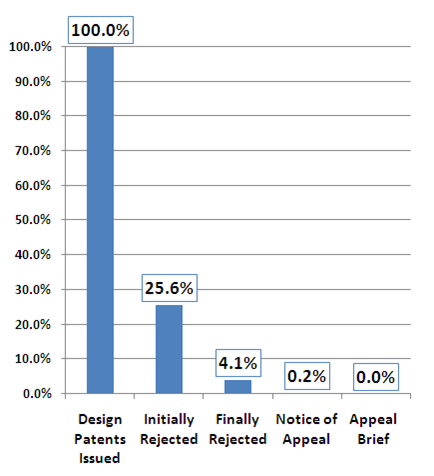

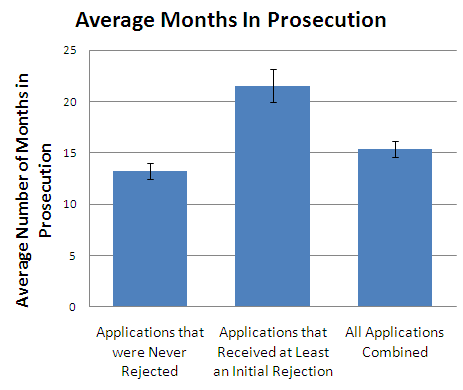

Over eighty percent of utility patent applications are initially rejected during prosecution. Some areas of technology – such as semiconductors – have a lower rejection rate while others – such as electronic commerce methods – have an even higher rejection rate.

Over eighty percent of utility patent applications are initially rejected during prosecution. Some areas of technology – such as semiconductors – have a lower rejection rate while others – such as electronic commerce methods – have an even higher rejection rate.

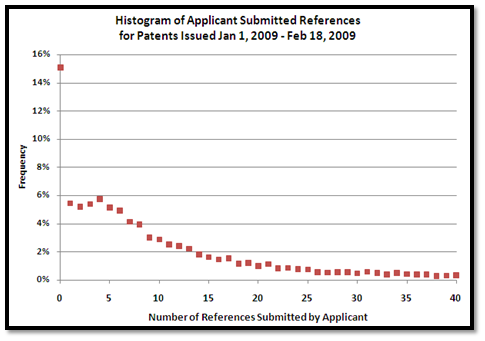

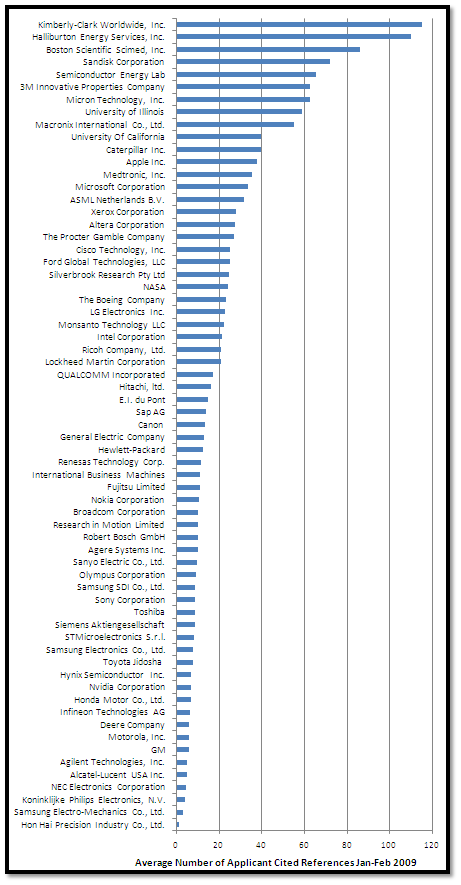

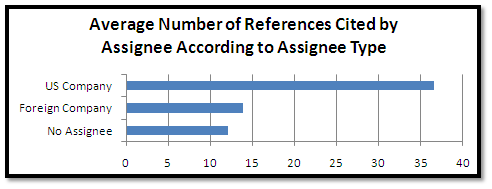

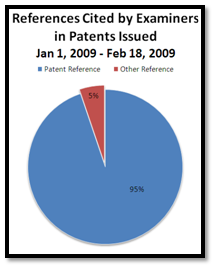

I compiled a list of the over five hundred thousand reference citations in the almost eighteen thousand utility patents issued in the past two months. (Jan 1, 2009 – Feb 18, 2009, excluding reissues and reexaminations). In this sample, the average patent issued with 31 cited references. This is a skewed average – the median patent only cites 15 references. The vast majority of references (77%) are introduced by the applicant during prosecution while less than a quarter (23%) are cited by the examiner.

I compiled a list of the over five hundred thousand reference citations in the almost eighteen thousand utility patents issued in the past two months. (Jan 1, 2009 – Feb 18, 2009, excluding reissues and reexaminations). In this sample, the average patent issued with 31 cited references. This is a skewed average – the median patent only cites 15 references. The vast majority of references (77%) are introduced by the applicant during prosecution while less than a quarter (23%) are cited by the examiner.