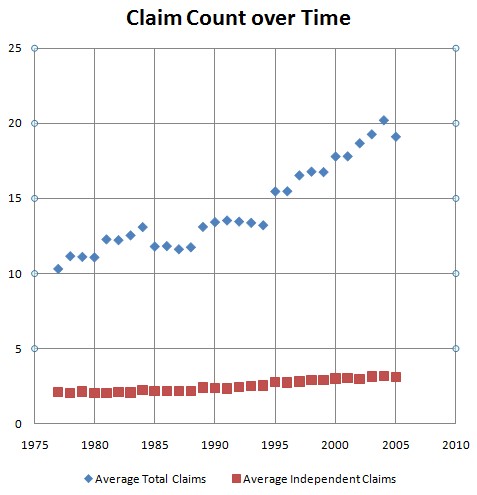

The chart shows the average number of total claims and independent claims for each year of issuance. The sample is drawn from 28,000 randomly selected patents that issued from 1977 and 2005. (For those who want data, the following table shows the average claim numbers by filing date.)