by Dennis Crouch

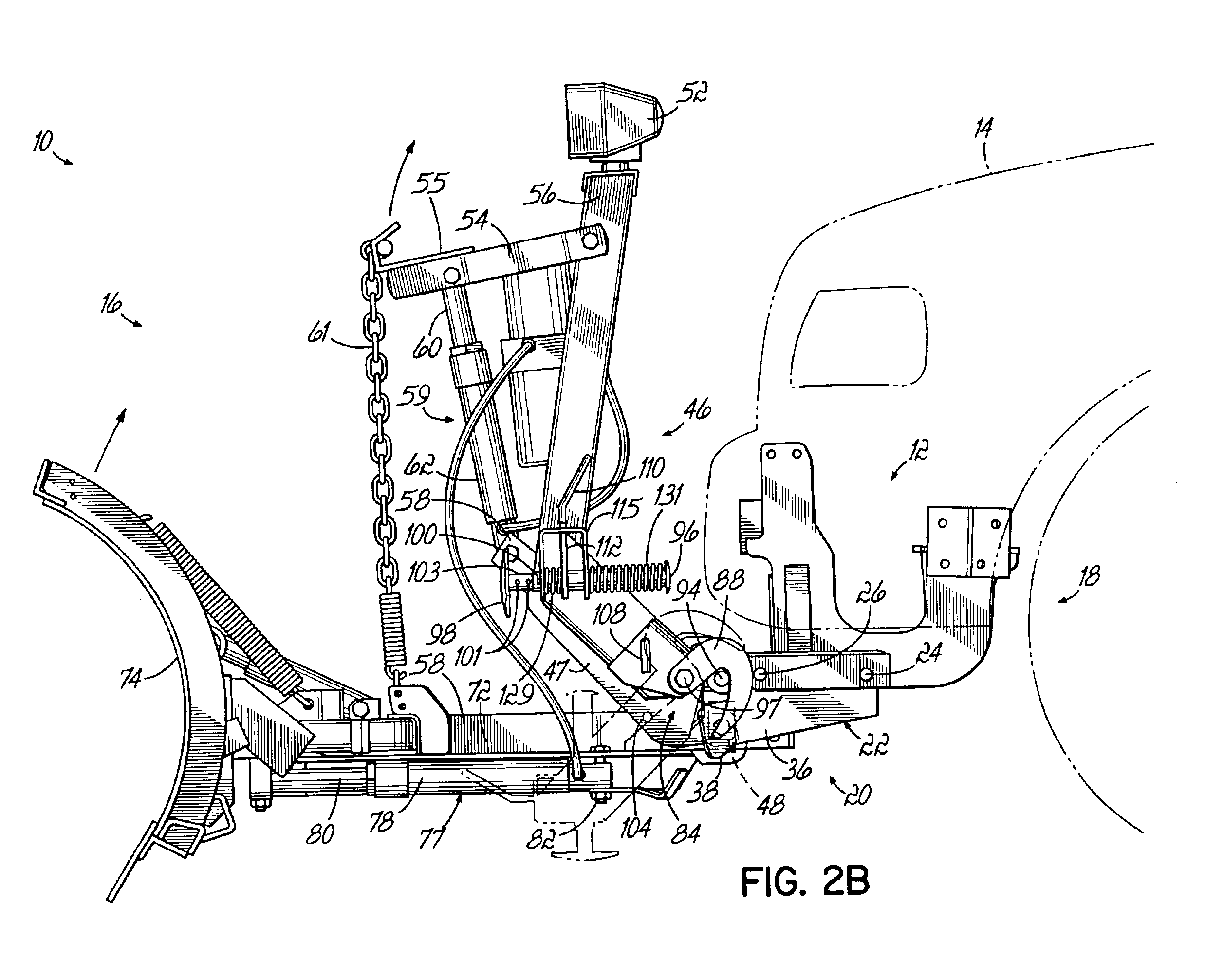

Douglas Dynamics v. Meyer Prods (W.D. Wisc 2017) [2017-04-18 (68) Order re post IPR invalidity defenses]. After Douglas sued Meyer for infringing its U.S. Patent No. 6,928,757 (Snowplow mounting assembly), Meyer petition for inter partes review -- alleging that several of the claims were invalid. Although the "director" iniated the review, the PTAB eventually sided with the patentee - reaffirming the validity of the claims.

After Douglas sued Meyer for infringing its U.S. Patent No. 6,928,757 (Snowplow mounting assembly), Meyer petition for inter partes review -- alleging that several of the claims were invalid. Although the "director" iniated the review, the PTAB eventually sided with the patentee - reaffirming the validity of the claims.

Back at the district court, Douglass asked the court to apply the estoppel provisions that of Section 315(e)(e):

The petitioner in an inter partes review ... that results in a final written decision under section 318(a) . . . may not assert . . . in a civil action arising [under the patent laws] . . . that the claim is invalid on any ground that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review.

35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2). The question for the district court here, was the scope of estoppel - what constitutes grounds that were "raised or reasonably could have [been] raised" during the IPR. Here, the court took a position for fairly strong estoppel:

If the defendant pursues the IPR option, it cannot expect to hold a second-string invalidity case in reserve in case the IPR does not go defendant’s way. In many patent cases, particularly those involving well-developed arts, there is an abundance of prior art with which to make out an arguable invalidity case, so it would be easy to have a secondary set of invalidity contentions ready to go. The court will interpret the estoppel provision in § 315(e)(2) to preclude this defense strategy. Accordingly, the court will construe the statutory language “any ground that the petitioner . . . reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review” to include non-petitioned grounds that the defendant chose not to present in its petition to PTAB.

In Shaw Industries Group, Inc. v. Automated Creel Systems, Inc., 817 F.3d 1293 (Fed. Cir.), the Federal Circuit wrote in dicta that no estoppel should apply to grounds that were petitioned, but not instituted. The Wisconsin court here suggested some potential problems with that outcome, but decided to follow the CAFC's lead, writing:

So until Shaw is limited or reconsidered, this court will not apply § 315(e)(2) estoppel to [petitioned but] non-instituted grounds, but it will apply § 315(e)(2) estoppel to grounds not asserted in the IPR petition, so long as they are based on prior art that could have been found by a skilled searcher's diligent search.

What this means for the defendant here is that the only 102/103 arguments that it gets to raise are ones already deemed total failures by the PTAB - and thus are unlikely winners before a district court.

= = = = =

Of some importance, the PTAB's final written decision was released in November 2016. For estoppel purposes, that final decision is all that is required for estoppel to kick-in. However, the case currently on appeal to the Federal Circuit -- already giving the defendant its second bite at the apple.

= = = =