by Dennis Crouch

ChargePoint, Inc., v. SemaConnect, Inc. (Supreme Court 2019) [Petition]

Another new eligibility petition, this one filed by by top Supreme Court Carter Phillips. Questions presented:

- Whether a patent claim to a new and useful improvement to a machine or process may be patent eligible even when it “involves” or incorporates an abstract idea.

- Whether the Court should reevaluate the atextual exception to Section 101.

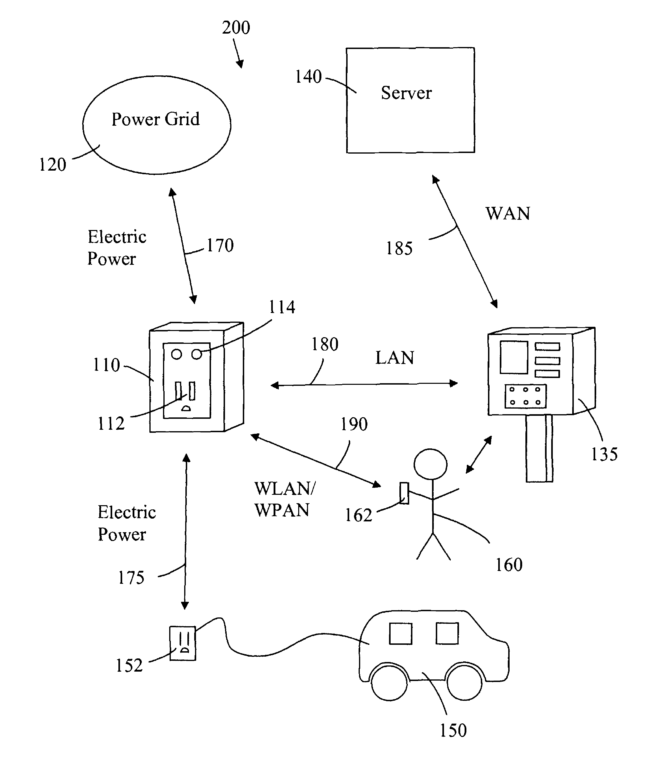

I drive a Honda Clarity -- a Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV) -- and use ChargePoint connected charging stations when I travel out of town. The patent here -- U.S. Patent No. 8,138,715* -- essentially covers remote-control of the charging station (i.e., via your phone). Asserted claim 1 requires a transceiver that receives a "turn on" signal from a remote server. The transceiver then sends a signal to a "controller" that then triggers a switch ("control device"). Dependent claim 2 adds an electrical coupler whose electric supply is switched on/off by the control device. My understanding is that all of these items could be configured within item 110 (below) that the inventors lexicographed as a "Smartlets™" -- although the claims do not require the apparatus to take the cute boxy-shape displayed below.

The district court dismissed the case for failure to state a claim -- finding the claims ineligible as a matter of law. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed with the following holdings:

Alice Step 1: The focus of the claims - as a whole - is the abstract idea of the internet-of-things (IoT): "communication over a network to interact with a device connected to the network." In reaching that conclusion, the court looked to "problem" identified in the specification -- a lack of communication network to allow for efficient charging control, including paying for the electricity consumed. From the specification, the court found it "clear that the problem perceived by the patentee was a lack of a communication network for these charging stations, which limited the ability to efficiently operate them from a business perspective."

In short, looking at the problem identified in the patent, as well as the way the patent describes the invention, the specification suggests that the invention of the patent is nothing more than the abstract idea of communication over a network for interacting with a device, applied to the context of electric vehicle charging stations.

The court went-on to hold that the claim breadth "would preempt the use of any networked charging stations."

Alice Step 2: At step-2, ChargePoint argued that it solved practical problems in the field by creating a new way of remote control and network control of a charging system. The problem for the Court was that the alleged inventive concept here is network control -- which the court already found to be the problematic abstract idea.

The court gives ChargePoint props for a good idea and implementation -- but the problem here really is the breadth of the claims that basically join together two well-known concepts.

In short, the inventors here had the good idea to add networking capabilities to existing charging stations to facilitate various business interactions. But that is where they stopped, and that is all they patented. We therefore hold that claim 1 is “directed to” an abstract idea. As to dependent claim 2, the additional limitation of an “electrical coupler to make a connection with an electric vehicle” does not alter our step one analysis.

Id.

The petition calls-out Alice as a "failed experiment" especially when placed "in the Federal Circuit's hands."

[T]he Federal Circuit and various parties have used the chaos that has trailed the Court’s decision to eliminate numerous patents. Indeed, the period following Alice has seen, by one estimate, a 914% increase in the number of patents invalidated under Section 101. [Citing Sachs]. Alice’s warning to “tread carefully in construing [the Section 101] exclusionary principle lest it swallow all of patent law,” 134 S. Ct. at 2354, has largely been realized.

Petition.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.