by Dennis Crouch

The following is my patent law exam from this past semester. As in years past, the exam was worth less than half of the final grade because the students did other substantial work during the semester, including a major moot court competition. Students were permitted access to their book/notes/internet, but were barred communications with another human during the exam.

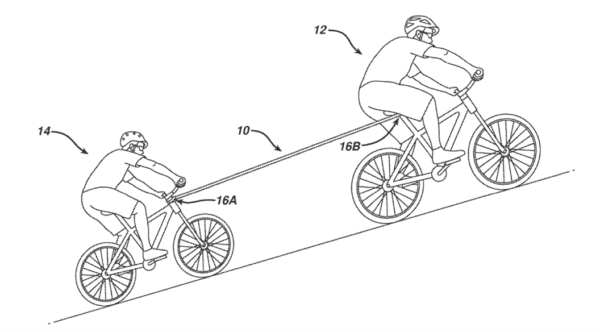

This year's exam is very loosely based upon an interesting patent that I found associated with the Tow Whee product created by Eric Landis. See US11167164, US11731470, and US11724148. But, the events described are entirely my creation.

= = =

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.