by Dennis Crouch

Throughout its 40-year history, the Federal Circuit has been largely negative toward the doctrine of equivalents (and exceedingly negative toward the reverse DOE). This negativity includes repeatedly taking decisions out of the jury’s hands based upon insufficient evidence of equivalency. In a new decision, a 2-1 majority continues this trend, holding that conclusory expert testimony is insufficient even for relatively simple technologies. NexStep, Inc. v. Comcast Cable Communications, LLC, No. 22-1815 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 24, 2024). Writing for the majority, Judge Chen affirmed the district court’s grant of JMOL overturning a jury’s DOE infringement verdict. Judge Reyna filed a sharp dissent arguing the majority imposed an unnecessarily rigid expert testimony requirement.

- Read the Decision: 22-1815.OPINION.10-24-2024_2408132

The Technology and Patents at Issue: The case involves two family-member patents related to streamlining technical support for consumer electronics. U.S. Patent Nos. 8,280,009 and 8,885,802. The ‘009 patent claims a “concierge device” that initiates technical support through a “single action” by the user – avoiding the hassle of providing model numbers and other device information when seeking help. The claimed invention allows the user to press just one button to start a support session, with the system automatically providing necessary device identification details. To that end, the claim includes a series of steps taken by the system “responsive to a single action performed by a user.” The ‘802 patent (which raised separate claim construction issues discussed below) similarly claims a digital butler system for controlling consumer electronics through voice commands over VoIP.

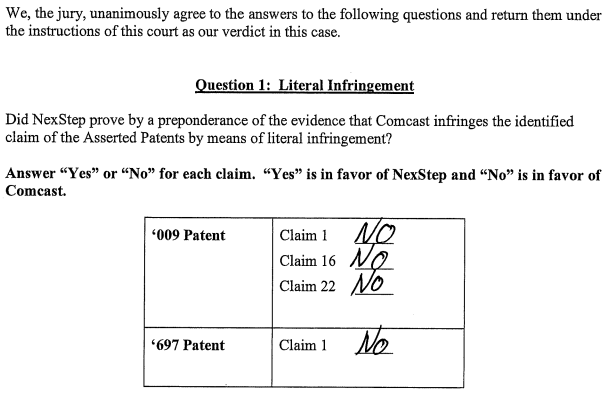

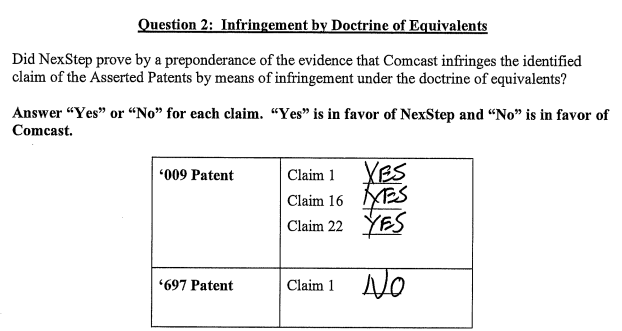

Procedural History and DOE Verdict: NexStep accused several features of Comcast apps of infringing the ‘009 patent. One problem though is that each feature seemingly required multiple button presses to initiate technical support. At trial, the jury found no literal infringement but determined the app infringed under the doctrine of equivalents. After initially entering the verdict, D.Del District Court Judge Andrews granted Comcast’s Rule 50(b) motion for JMOL, finding that no reasonable jury could have found infringement based upon the evidence presented at trial. In particular, NexStep’s expert testimony was insufficient to support the DOE verdict.

Expert Testimony Requirements for DOE?: The Federal Circuit’s analysis focused on whether NexStep’s expert, Dr. Selker, provided the “particularized testimony and linking argument” required to support a DOE verdict. See Texas Instruments Inc. v. Cypress Semiconductor Corp., 90 F.3d 1558 (Fed. Cir. 1996). Dr. Selker testified that the “several button presses” in Comcast’s app performed substantially the same function in substantially the same way to achieve substantially the same result as the claimed “single action.”

The majority found this testimony fatally deficient for several reasons:

1. Failed to identify specific equivalent elements – Dr. Selker’s reference to “several button presses” did not identify which specific elements in the accused products were allegedly equivalent to the claimed “single action.” Although during his literal infringement testimony, Dr. Selker had specifically identified the button press sequences, he did not particularly talk through what aspects of those sequences were equivalent to the single button push.

2. No explanation of “why” – Even if specific elements were identified, Dr. Selker failed to explain why someone would conclude that those elements were performing substantially the same function, way, and result — other than conclusory statements that were deemed insufficient without supporting analysis.

3. Misaligned function identification – Dr. Selker’s did identify the overall function of the invention (“to diagnose your device”), but did not provide testimony regarding how the alleged equivalents align with the function of the “single action” limitation.

The majority emphasized that these requirements apply regardless of technological complexity, rejecting NexStep’s argument for a more flexible approach with simple technologies. In the process, the court cited to Warner-Jenkinson for the proposition that it has a central role in ensuring that the doctrine is not abused. See Warner-Jenkinson Co. v. Hilton Davis Chem. Co., 520 U.S. 17, 39 n.8 (1997) (“[T]he various legal limitations on the application of the doctrine of equivalents are to be determined by the court”).

Sharp Dissent on Expert Testimony Standard: Judge Reyna dissented from the DOE analysis, arguing the majority “concocts a rigid new rule that in all cases a patentee must present expert opinion testimony to prove infringement under the doctrine of equivalents.” The dissent contended this contradicts precedent recognizing that expert testimony is just one way to prove equivalence. See AquaTex Indus., Inc. v. Techniche Sols., 479 F.3d 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (evidence can come from expert testimony; by documents such as texts and treatises; and via prior art disclosures).

More fundamentally, Judge Reyna argued the majority failed to properly apply the substantial evidence standard under Third Circuit law, which requires JMOL only in “extraordinary circumstance[s]” where no evidence could support the verdict. Avaya Inc., RP v. Telecom Labs, Inc., 838 F.3d 354 (3d Cir. 2016). The dissent contended Dr. Selker’s testimony, viewed in totality with his literal infringement testimony, provided sufficient explanation of why multiple button presses were equivalent to a single action. It is a big deal to strip a party of their Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial, and so rightly limited.

Expert Testimony and DOE: I want to circle back and make sure we look carefully at the Majority Decision for a moment. The majority does not expressly create an expert testimony requirement and is careful to cite its AquaText statement that DOE can be proven using other evidence. However, the decision also goes on to require “particularized testimony” that links the claim to the accused equivalents via the function/way/result or insubstantial differences frameworks. And, even in simple situations where the insubstantiality could be apparent, a particularized explanation is necessary. As I sit here, I cannot think of any way that a mere fact-witness could provide this particularized testimony absent some smoking-gun document involving the accused infringer making admissions about how its product was attempting to mimic the patented invention. On this point, I’ll note that the patentee’s brief mentions additional evidence of equivalents, including certain “Comcast Technical Documents and Source Code” as well as cross examination of two comcast experts. The court’s failure to mention these in its opinion indicates to me that it is effectively requiring direct expert testimony in order for a patentee to win on DOE.

In Texas Instruments v. Cypress Semiconductor, the Federal Circuit held that a patentee must provide “particularized testimony and linking argument” regarding the “insubstantiality of the differences” between the claimed invention and the accused device, or with respect to the function/way/result test if that evidence is presented. The court explained that this requirement exists because, while the DOE standard is simple to articulate, it is “conceptually difficult to apply.” The evidentiary requirements serve to ensure the fact-finder has a proper analytical framework and doesn’t “erase a plethora of meaningful structural and functional limitations of the claim on which the public is entitled to rely in avoiding infringement.” While TI had provided expert testimony in the case, the testimony was deemed insufficient because it consisted merely of conclusory statements about overall similarity rather than a detailed explanation of why specific differences were insubstantial. More recently, in VLSI Technology LLC v. Intel Corporation, No. 2022-1906 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 4, 2023), the court reversed a judgment of infringement under the doctrine of equivalents as a matter of law because the patentee, failed to provide sufficient particularized testimony and linking argument. The VLSI court explained its reticence toward the doctrine as providing only “a limited exception to the principle that claim meaning defines the scope of the exclusivity right” and that DOE liability should be seen as “exceptional.” The VLSI decision went on to state that proof of DOE infringement must include both “specificity and completeness.”

I see the NexStep majority opinion as largely falling in line with TI and VLSI, extending the particularized testimony requirements to include even the simplest of cases. From one perspective, this seems to be a fairly straightforward principle — it would have seemingly been easy for NexStep’s expert to present the testimony that particularly linked the multiple steps as an equivalent to the single step claim limitation. I expect that the difficulty here was similar to most DOE cases where the patentee was alleging both literal and DOE infringement, and explaining these DOE issues with particularity raises the risk of undermining the literal infringement case. However, I expect that there are clear ways to present the testimony for a prepared team.

Attorney: You testified that Comcast’s product uses a single step, but Comcast has told us it will argue that its product requires multiple steps. Is that still infringing?

Expert: I have two things to say about that – first that it is best seen as a single step; and second, even if it does require a little more from the user, it is still infringement under the DOE — let me explain [provides particularized testimony]…

This type of testimony framework would allow the expert to maintain the literal infringement position while also providing the particularized testimony needed for DOE. Under NexStep, it seems that the patentee will need to present these alternative theories in its case in chief rather than waiting for rebuttal.

Claim Construction Issue: The Federal Circuit also addressed claim construction of “VoIP” in the ‘802 patent claims. The district court construed VoIP as requiring capability for two-way communication. The court rejected NexStep’s argument for a broader construction that also included one-way audio transmission.

Notably, NexStep had agreed below that VoIP was an established industry term that should carry its ordinary meaning to skilled artisans — but the parties disagreed over what that meaning should be. The Federal Circuit found no clear error in the district court’s factual findings about that meaning based on technical dictionaries defining VoIP in the context of voice conversations and telephony services. The specification’s repeated association of VoIP with telephone services supported this construction.

The doctrine of equivalents for stretching claim scope for infringement [DOE] was never intended to just delete a key novel express claim limitation here like “responsive to a single action performed by a user” and replace it with its exact opposite – several different actions. [Why it could not have been rejected on that basis alone, rather than lack of expert evidence, is amazing to me.]

I disagree with this. DOE always covers something excluded by the literal claims themselves. If a one-click system is designed to be more efficient/accurate – there may be a two click approach that achieves this same level of benefits via a slightly different way.

The DOE doctrine allows the patentee “to claim those insubstantial alterations that were not captured in drafting theoriginal patent claim but which could be created through trivial changes.” Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., 535 U.S. 722, 733 (2002). I do not see how the proposed-to-be-ignored claim limitation here was insubstantial or a trivil change, IF, as I understood, the claimed “way” of accomplishing the desired result – only needing to press a single button to send plural info signals rather than several buttons – was the key inventive feature, and to replace it with several button presses is the its exact opposite, not a mere unnecessary lower range limit as in Warner-Jenkinson Co. v. Hilton Davis Chem. Co., 520 U.S. 17, 39 n.8 (1997). ? Or, did the patent and its prosecution [which I have not read] indicate that this claim limitation was not any material part of the invention? [A factual dispute.]

The claims here are directed to a “single action” — and that term’s ambiguity creates an interesting challenge for claim interpretation and the doctrine of equivalents. Even a seemingly simple button press can be decomposed into multiple discrete physical actions – moving a finger, applying pressure, releasing pressure, along with countless neural signals and muscle movements.

A phone call analogy is particularly instructive. When someone says “I made a phone call today,” they’re conceptualizing multiple button presses as a single action. Nobody would say “I performed 10 separate actions by pressing 2-1-3-5-5-5-1-2-1-2.” Rather, we intuitively group these related inputs into one conceptual action. (The patentee used this analogy in the case).

If Comcast’s multiple button presses still achieve the core benefit of simplified support access without requiring separate device identification steps, they may be functionally equivalent to a “single action” despite involving multiple physical inputs – provided this equivalence is properly supported by particularized expert testimony explaining these functional parallels.