by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit today issued two related opinions in long-running patent litigation between Cellspin and various technology companies including Fitbit, Nikon, Nike, and others. The decisions highlight important procedural issues in patent litigation while also addressing the timing requirements for judicial recusal motions. Collectively, they highlight the reality that the outcome of complex civil litigation often turns on procedural issues.

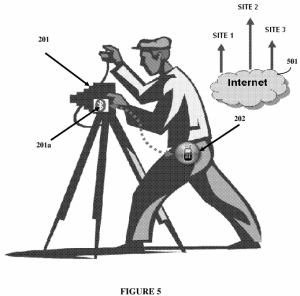

The litigation involves three Cellspin patents (U.S. 8,738,794; 8,892,752; and 9,749,847) all related to automatically uploading multimedia content. The patents describe a system where a data capture device (like a camera) connects to a mobile device via Bluetooth, which then automatically publishes the content online. Key claim elements included requirements for:

- A “user identifier” attached to data

- A continuously maintained “paired connection” between devices

- Specific processor configurations for data handling

Summary Judgment: Local Rules and Timing Matter

In the first decision, the Federal Circuit affirmed summary judgment of non-infringement on multiple grounds, with a key ruling centering on Cellspin’s belated attempt to rely on “OAuth” to satisfy the “user identifier” claim element. While this argument might have some merit, N.D. Cal. Judge Rodgers refused to permit the argument because it was proposed too late in the pretrial litigation process.

Pretrial civil litigation procedure is largely designed with an iterative process to expose and narrow issues – both for efficiency and to prevent “trial by ambush.” At the foundation, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure establish baseline requirements, with Rule 26 mandating initial disclosures of key witnesses and documents, and Rules 33-36 providing tools for further discovery of factual contentions through interrogatories, document requests, and requests for admission. Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U.S. 495 (1947) (explaining how the federal rules replaced “the old procedural boxing match and concealment” with “a rational method of inquiry”; while still protecting privileged and certain work-product documents). Building on this foundation, many district courts have adopted local rules providing additional structure, with patent cases often subject to specialized local patent rules requiring detailed infringement and invalidity contentions at specific early stages. See O2 Micro Int’l Ltd. v. Monolithic Power Sys., Inc., 467 F.3d 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2006) (upholding local patent rules designed to “require parties to crystallize their theories of the case early in the litigation”). Individual judges then frequently impose additional requirements through standing orders, as well as case-specific scheduling orders tailored to particular disputes. This multi-layered approach attempts to balance the need for uniform procedural standards against the reality that different types of cases—and different judges—may require different management approaches to achieve efficient resolution.

The Northern District of California has adopted a set of Local Patent Rules that are among the most aggressive in the country. Importantly for this case, the patentee is required to provide detailed infringement contentions at an early stage. Patent Local Rule 3-1(c). Although these contentions can be amended, that process requires “good cause” and also requires the patentee to actively seek such amendment rather than simply introducing new theories via expert reports. Patent Local Rule 3-6.

In June 2020, Cellspin served its infringement contentions identifying how the “user identifier” limitation was met, pointing to “username or email address, or information based off of a user or the user’s associated wearable device.” However, Cellspin waited until September 2021—at the close of fact discovery—to first argue that the defendants’ use of OAuth satisfied this claim limitation. The district court excluded this new OAuth theory, noting that Cellspin had never sought to amend its contentions under Local Rule 3-6. On summary judgment, with the OAuth theory excluded, the court sided with the accused infringer – finding no genuine dispute that the accused products (as originally argued) satisfied the user identifier limitation.

On appeal, Cellspin argued that the district court abused its discretion in excluding the OAuth theory, contending that the information was produced late in discovery and that strict enforcement of the local rules elevated procedure over substance. The Federal Circuit disagreed, affirming the district court’s exclusion of the OAuth theory and the resulting summary judgment. The appellate panel emphasized that Cellspin had clear procedures available to amend its contentions but failed to utilize them, writing that “whether the standards for amendment would have been met . . . was never tested.” The court found no abuse of discretion in requiring parties to follow the established procedures for amending contentions rather than allowing new theories to be introduced through expert reports, explaining that this approach aligns with the fundamental purpose of local patent rules in promoting early disclosure of infringement theories.

The Recusal Challenge: Too Little, Too Late

A second decision addressed Cellspin’s attempt to vacate the summary judgment based on alleged grounds for judicial recusal under 28 U.S.C. § 455. The key wrinkle was that Fitbit had become a Google subsidiary in February 2021, which Cellspin argued created various conflict issues given the judge’s and her husband’s financial and professional connections.

Cellspin’s recusal motion presented three distinct categories of alleged conflicts, each handled differently by the Federal Circuit. The investment-related arguments focused on Judge Gonzalez Rogers’s and her husband’s holdings in large independently managed multi-company funds that included Google stock in their portfolios. The McKinsey-related arguments centered on Mr. Rogers’s long-term employment at McKinsey (which lasted until March 2021) and that firm’s general business relationship with Google, including offering Google cloud services to McKinsey clients – though notably without evidence of Mr. Rogers’s direct work with Google given his focus on energy sector clients. Both of these grounds were rejected as untimely because the underlying facts were publicly available well before summary judgment – the judge’s investments had been disclosed since 2012, and Google’s acquisition of Fitbit was known by February 2021. An Ajax-related argument stood on different footing, involving Mr. Rogers’s more recent role as “Operations Partner” at Ajax Strategies Venture Capital, allegedly funded in part by Google. While the Federal Circuit declined to decide whether this relationship required recusal under § 455(a), it found that any error would be harmless given that the court’s affirmance of summary judgment against other defendants (Garmin and Fossil) on the OAuth issue – for which no recusal challenge was preserved – would have the same preclusive effect against Fitbit.

The Federal Circuit’s analysis of the recusal issue was largely decided on timeliness. While § 455 doesn’t specify a time limit, courts have often held that recusal motions must be brought with “reasonable promptness” after discovering the grounds for recusal. E. & J. Gallo Winery v. Gallo Cattle Co., 967 F.2d 1280, 1295 (9th Cir. 1992). The court found most of Cellspin’s arguments untimely since they were based on publicly available information known well before the summary judgment ruling.

In my view, an important aspect of this timing decision is that the recusal arguments fell under § 455(a), which addresses general circumstances where a judge’s “impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” In contrast, § 455(b) lists specific circumstances requiring mandatory disqualification—such as where the judge has a financial interest in the subject matter or personal knowledge of disputed facts—and these grounds operate as bright-line rules that apply regardless of whether the judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned by an objective observer.

In this case, the court did not reach any § 455(b) grounds because there were no allegations, such as direct stock ownership that would trigger § 455(b)’s mandatory disqualification provisions. Although Cellspin raised issues about investments and business relationships that might superficially sound like § 455(b) financial interest concerns, the indirect nature of these connections (through mutual funds and business relationships) placed them in the § 455(a) realm of potential appearance issues rather than § 455(b)’s bright-line rules.

Deeper Dive into the N.D.Cal. Patent Local Rules

I wanted to turn back for a moment to the Northern District of California’s Patent Local Rules. The Patent Local Rules create a fairly regimented framework for patent litigation that served as a nationwide model for a number of other districts. The rules apply broadly to “all civil actions filed in or transferred to this Court which allege infringement of a utility patent in a complaint, counterclaim, cross-claim or third party claim, or which seek a declaratory judgment that a utility patent is not infringed, is invalid or is unenforceable.” Patent Local Rule 1-2. This comprehensive scope ensures consistent handling of patent matters throughout the district.

The rules establish timelines and detailed requirements for infringement contentions. Under Patent Local Rule 3-1, within just 14 days after the Initial Case Management Conference, a party claiming infringement must serve its “Disclosure of Asserted Claims and Infringement Contentions.” These contentions must include specific information, including “a chart identifying specifically where and how each limitation of each asserted claim is found within each Accused Instrumentality.” This early disclosure requirement forces patent holders to do their homework up front and prevents shifting theories as the case progresses. Recognize that at this point in the litigation, there has been almost no discovery. In practice, this means that the contentions require regular updating.

The rules create a somewhat balanced approach by imposing detailed requirements on accused infringers. For instance, under Patent Local Rule 3-3, within 45 days of receiving infringement contentions, the accused infringer must provide its invalidity contentions, including detailed claim charts showing “specifically where and how in each alleged item of prior art each limitation of each asserted claim is found.”

Although these rules operate district wide, they also provide liberal allowance for judges to alter the rules as they see fit. Patent Local Rule 1-3, titled “Modification of these Rules,” states:

The Court may modify the obligations or deadlines set forth in these Patent Local Rules based on the circumstances of any particular case, including, without limitation, the simplicity or complexity of the case as shown by the patents, claims, products, or parties involved. Such modifications shall, in most cases, be made at the initial case management conference, but may be made at other times upon a showing of good cause.

The rule also encourages parties to work together on proposed modifications. The local rules particularly require the parties to discuss any proposed modifications at the initial Rule 26(f) conference.

Particularly relevant to the Cellspin case is Patent Local Rule 3-6’s standard for amending contentions. The rule requires “a timely showing of good cause” for any amendment, providing specific examples like claim construction rulings different from those proposed or “recent discovery of material prior art despite earlier diligent search.” Importantly, the rule explicitly states that “[t]he duty to supplement discovery responses does not excuse the need to obtain leave of court to amend contentions.” This framework is designed to protect against shifting theories while still providing flexibility – but only through a formal amendment process that requires court approval. As the Cellspin decision reinforces, these rules are essentially an added layer of procedure that requires thoughtful and timely action by the attorneys — at risk of losing the ability to make certain arguments.

In my opinion, patent litigation’s heightened procedural requirements typically favor accused infringers, particularly large corporate defendants, for several strategic reasons. These defendants often deploy well-staffed litigation teams, including procedural mavens with deep experience navigating complex procedural rules and specialized local patent rules. The front-loaded disclosure requirements, such as N.D. Cal.’s Patent Local Rule 3-1’s detailed infringement contentions, create opportunities for early dispositive motions based on procedural non-compliance or crystallized theories that prove deficient. While plaintiffs’ attorneys often seek to drive cases toward trial, defendants’ counsel more typically look to leverage these procedural requirements as off-ramps – whether through early dismissal on the pleadings, claim construction, summary judgment, or other pretrial resolution. As we see in Cellspin, a procedural misstep in amending infringement contentions can lead to case-dispositive summary judgment without ever reaching the substantive merits.

Of course, these are generalizations, and although I believe there is often an asymmetric burden, that may just be a reality of litigation where the plaintiff generally has the burden of overcoming these hurdles and proving its case.

I remember studying Civ Pro twenty years ago that indicated that civil procedures were to allow proper judging of the merits of the cases and not to allow procedure to make substantive determinations of a case. This case seems to hearken back to the gilded age where the powerful denied access to justice with Byzantine court procedures. Granting a summary judgement due to an obscure local court rule denying the patent owners 14th amendment right to due process and 7th amendment right to a jury seems like something out of a Dickens tale.

Millions of dollars spent on dozens of attorneys over a long time period, using substantial judicial resources even on procedural issues. Yet, no judicial consideration whatsoever of prior art and the 103 validity of the subject patents. Leaving patent owners free to sue others.

Precisely why reexaminations, IPRs and PRGs were enacted.