by Dennis Crouch

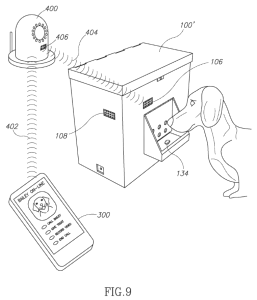

The Federal Circuit has affirmed summary judgment of non-infringement in DoggyPhone LLC v. Tomofun LLC, agreeing to narrowly construe the claim as requiring direct rather than indirect causation. The case involves U.S. Patent 9,723,813, which covers an "Internet Canine Communication System" that allows pet owners to remotely interact with and deliver treats to their dogs. DoggyPhone accused Tomofun's popular Furbo device of infringement, but both the district court and Federal Circuit found the accused product operates differently than what was claimed. Writing for the unanimous panel, Judge Hughes focused particularly on one key limitation requiring that the system "begins transmission to the remote client device of at least one of the audio or video of the pet in response to input from the pet."

At the heart of the dispute is a basic infringement question - whether Furbo's notification system satisfied the "begins transmission" limitation. When a dog barks, the Furbo sends a text notification to the owner's phone, but critically, no audio or video transmission begins until the owner actively clicks on that notification. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that this setup does not meet the claim limitation because "transmission begins not in response to the pet's activity, but in response to the user's decision to click on the notification—making transmission responsive to the user's input, not the pet's."

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.