by Dennis Crouch

Let me peel back the layers of this slippery copyright dispute that has the art world going bananas. In Morford v. Cattelan, No. 23-12263 (11th Cir. 2024), the Eleventh Circuit confronted the question of whether an artist can claim copyright protection over the concept of taping a banana to a wall. The appellate court sided with the accused famous artist, Morford continues to pursue his copyright action in a newly filed petition for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court.

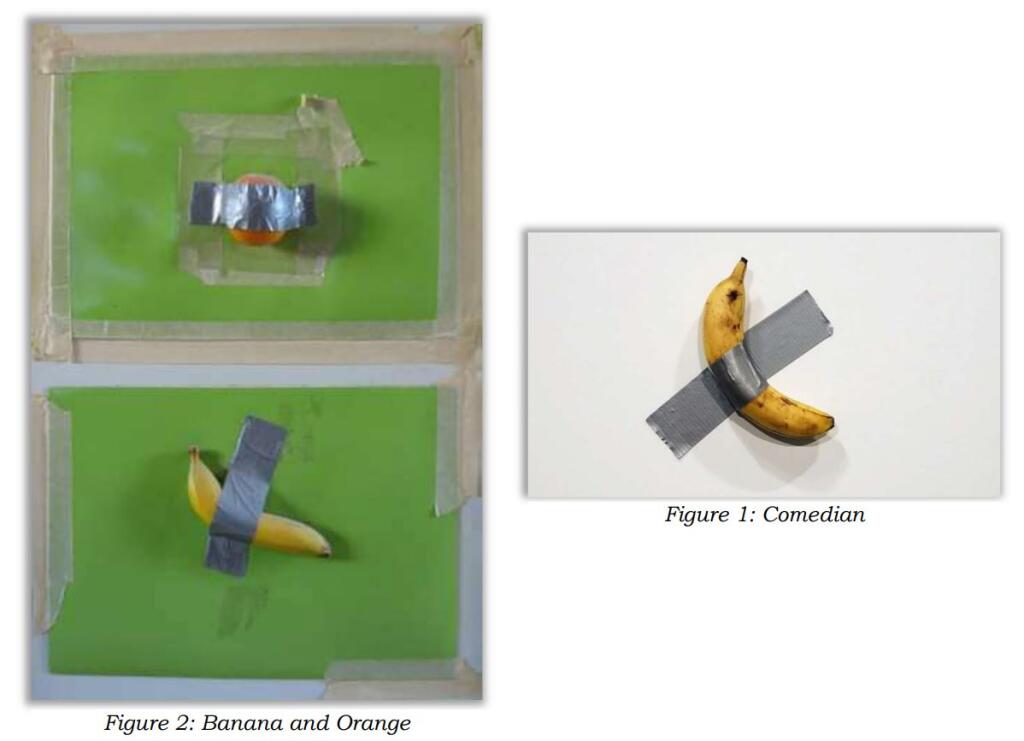

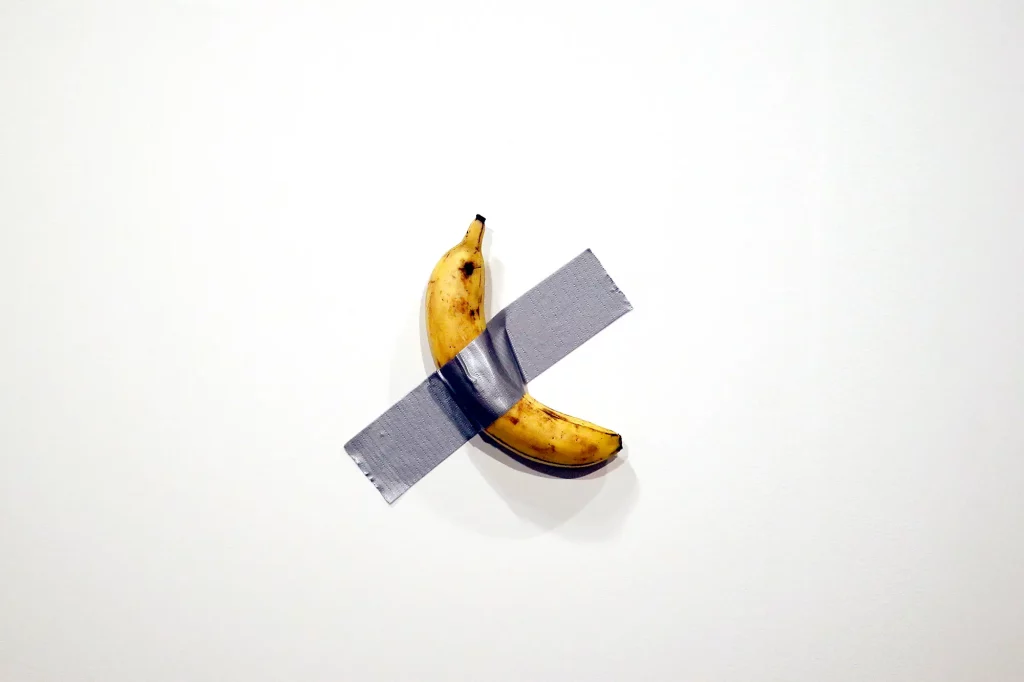

The core dispute stems from Maurizio Cattelan’s notorious work “Comedian” (2019), which sold for an eye-peeling $120,000 at Art Basel Miami — and later garnered a $6 million price for one of a limited edition of three. Morford claimed this work infringed his earlier piece “Banana and Orange” (2000), arguing that Cattelan’s work copied his original expression. However, both the district court and the Eleventh Circuit, rejected the arguments — siding with Cattelan.

Copyright infringement requires proof of copying. And one way to achieve that proof is to show that the accused infringer had access to the original work. Here, the court found Morford’s evidence was too thin to support his claim that Cattelan had access to his work. Citing Herzog v. Castle Rock Ent., 193 F.3d 1241 (11th Cir. 1999), the court held that mere internet availability through Facebook, YouTube, and a blog post wasn’t enough to establish Cattelan had a “reasonable opportunity to view” the work without further evidence of widespread dissemination or a direct connection between the artists.

On substantial similarity, the court applied the “abstraction-filtration-comparison” test from Compulife Software Inc. v. Newman, 959 F.3d 1288, 1301 (11th Cir. 2020). After filtering out unprotected elements through the merger doctrine, the court found the remaining protected elements distinctly different – including the angle of placement, background, and overall presentation. In the filtration step, the court found that Morford could not claim protection for the general idea of affixing a banana to a wall using duct tape. Further, the court found that the “X” shape created by the duct tape crossing the banana perpendicularly was also not protectable because it was the only practical way to tape a banana to a wall without obscuring the banana.

Morford’s petition to the Supreme Court raises three arguments. First, it identifies a 4-4 circuit split on whether “bodily appropriation” or “substantial similarity” should be the standard for compilation works. This split has created a situation where artists might have different rights depending on which circuit they slip into. Second, the petition challenges the “inverse ratio rule” which requires works with less public exposure (or less evidence of access) to show a higher degree of similarity to prove copying. Morford argues this rule is particularly problematic in the internet age, where works can be simultaneously accessible worldwide yet not necessarily “popular” in traditional terms. See Skidmore v. Zeppelin, 952 F.3d 1051 (9th Cir. 2020). Finally, Morford argues the lower courts misapplied the merger doctrine by essentially finding there are limited ways to tape a banana to a wall.

The Supreme Court might find this case appealing as a vehicle to address several (banana) split issues in copyright law.

We’ll see if the case is ripe for review,