by Dennis Crouch

In a significant decision narrowing the scope of Inter Partes Review (IPR) estoppel, the Federal Circuit has held that a patent challenger who previously pursued an IPR can still rely on system prior art in district court litigation, even when that system was fully documented in publications that could have been raised during the IPR. A key implication from this case is that despite the estoppel provision, a printed publication from an IPR can be later used in the litigation as part of the same combination of references used in the IPR, so long as the publications are categorized by the patent challenger in the litigation as proving that the invention was known/used/on-sale. Ingenico Inc. v. IOENGINE, LLC, No. 23-1367 (Fed. Cir. May 7, 2025). Writing for a unanimous panel, Judge Hughes explained:

IPR estoppel does not preclude a petitioner from relying on the same patents and printed publications as evidence in asserting a ground that could not be raised during the IPR, such as that the claimed invention was known or used by others, on sale, or in public use.

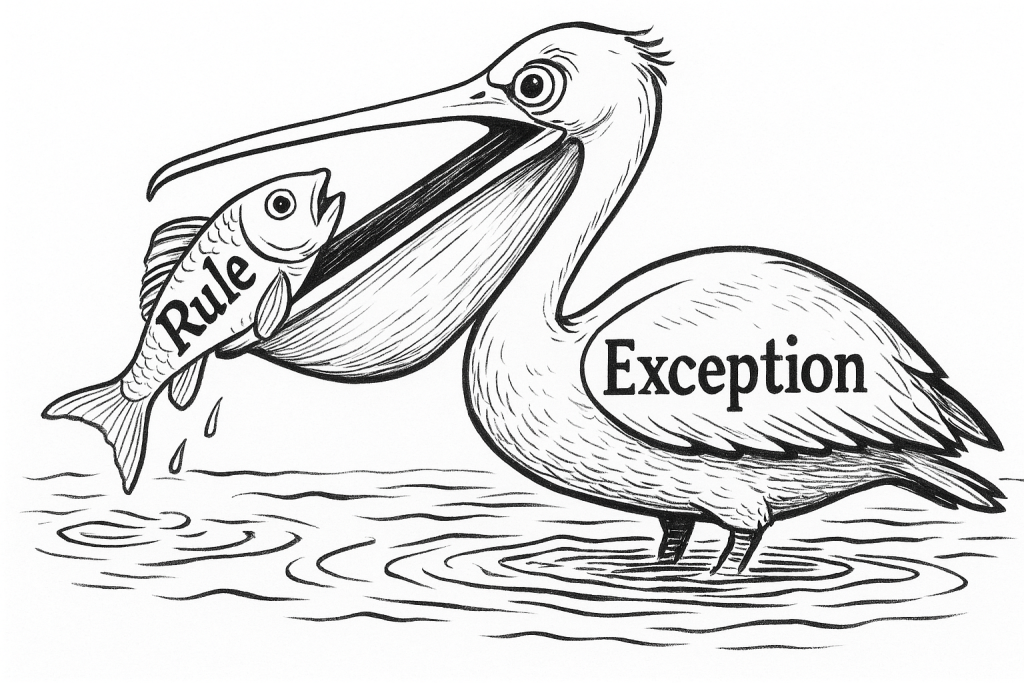

The decision resolves a long-standing split among district courts regarding the proper interpretation of the term "ground" in 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2), which bars IPR petitioners from asserting in district court "any ground that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review." The Federal Circuit held that "ground" refers to the specific statutory basis for invalidity (e.g., anticipation or obviousness based on patents or printed publications), not the prior art references themselves. The Federal Circuit clarified that 'ground' refers specifically to the statutory bases available in an IPR (anticipation or obviousness via patents/printed publications). As such, petitioners remain free to use identical prior art evidence to support district court invalidity grounds not available in IPR—such as prior public use or sale.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.