by Dennis Crouch

The Supreme Court recently received a petition for certiorari from NexStep, Inc., challenging a Federal Circuit decision that epitomizes a four-decades-long trend of restricting the doctrine of equivalents (DOE). The petition in NexStep, Inc. v. Comcast Cable Communications, LLC (No. 24-1137), presents a fundamental question: Has the Federal Circuit improperly shackled the doctrine of equivalents with rigid, formulaic requirements contrary to Supreme Court precedent? More particularly, the petition asks: "Whether a patentee must in every case present 'particularized testimony and linking argument' to establish infringement under the doctrine of equivalents."

- Dennis Crouch, Doctrine of Equivalents: Expert Testimony Must Include Particularized Links, Patently-O (Oct. 22, 2024) (discussion of the original CAFC decision).

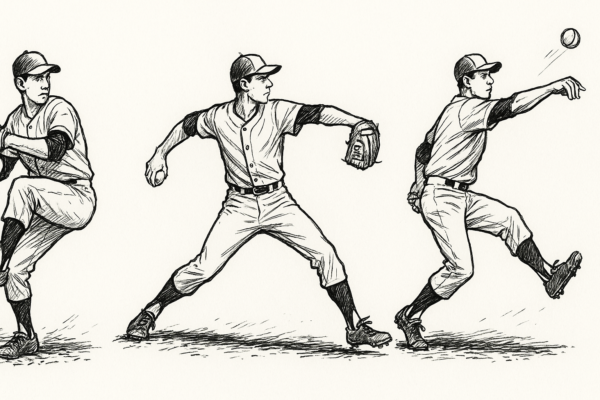

The case also has a nice baseball analogy. The patent requires a "single action" performed by a user, and the accused device needs three button pushes. The patentee's expert, when presenting the DOE case to the jury, used a baseball pitcher analogy - recognizing that throwing a ball includes numerous small steps to accomplish the single action of throwing. The argument here, which the jury agreed was meritorious, is that the three button pushes - while not literally the same as a single action - was the equivalent and thus infringing. The Federal Circuit wanted more - holding that the jury did not have enough evidence to reach that conclusion.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.