by Dennis Crouch

Samsung and the U.S. government have filed briefs urging the Supreme Court to deny certiorari in Lynk Labs, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., No. 25-308. At issue is whether a patent application filed before a challenged patent’s priority date, but not published until afterwards, can serve as prior art in inter partes review. The Federal Circuit held that it can, applying the filing-date rule of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(e)(1). As I write below, I was not overly impressed with they briefing.

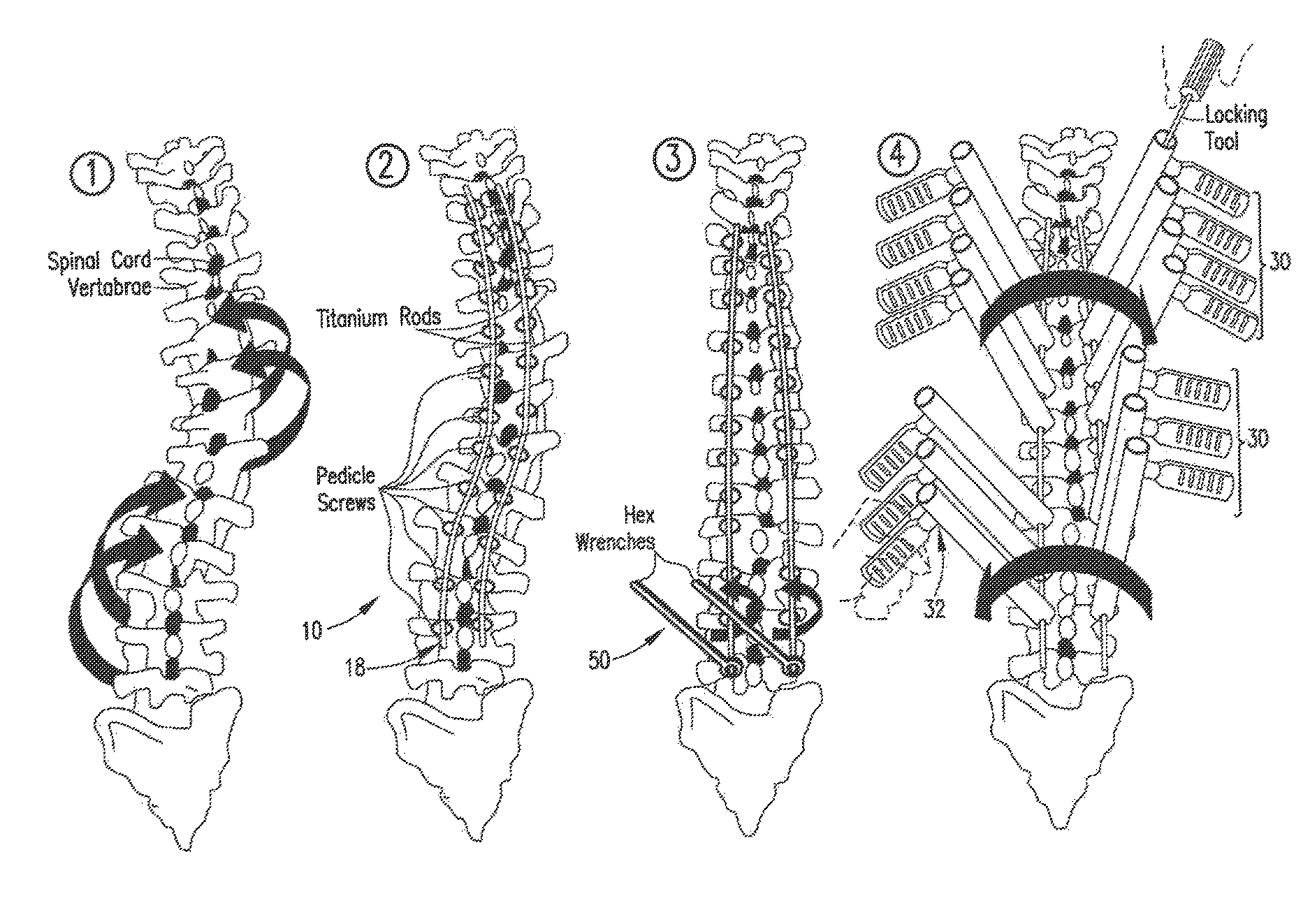

The case centers on the “Martin” reference, a patent application covering LED technology that was filed on April 16, 2003 and published on October 21, 2004. Martin was later abandoned and never became a patent. Lynk Labs’ ‘400 patent claims a priority date of February 25, 2004, placing it squarely in the gap between Martin’s filing and publication dates. Samsung successfully used Martin to challenge claims of the ‘400 patent as obvious in IPR.

As part of its streamlining effort, Congress limited what prior art can be used in inter partes review proceedings – only “prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” 35 U.S.C. § 311(b). Although Martin was not publicly accessible when Lynk Labs filed its application, Martin was later published and also qualifies as prior art under pre-AIA 102(e)(1) (or its parallel post-AIA statute 102(a)(2)). In reading the statute, the court concluded that Martin can be used in an IPR because it satisfies each of the two requirements (prior art + printed publication) even though its prior art date is well before its publication date. Lynk’s cert petition frames this as a question about whether “printed publications” in § 311(b) carry the traditional public-accessibility timing requirement, or whether a published patent application can be backdated as prior art to its filing date in IPR.

I have previously written about this case at several stages. Dennis Crouch, Secret Springing Prior Art and Inter Partes Review, Patently-O (Oct. 2024); Dennis Crouch, Publications Before Publishing and the Federal Circuit’s Temporal Analysis, Patently-O (Jan. 2025); Dennis Crouch, Prior Art Document vs. Prior Art Process, Patently-O (July 2025); Dennis Crouch, Supreme Court Asked to Resolve “Secret Springing Prior Art” in Inter Partes Review Proceedings, Patently-O (Sept. 2025); Dennis Crouch, Lynk Labs: How the Least-Vetted Documents Destroy Issued Patents, Patently-O (December 2025).

Before getting into the merits of the responses, I first want to note how both briefs appear shockingly disingenuous in their discussion of the limited impact of the decision. (more…)