Tag Archives: Federal Circuit En Banc

Court Publicly Reprimands Ed Reines, Recipient of Email from then-Chief Judge Rader (to be updated)

US Government Volunteers to Pay for Infringement by Japan Airlines

Sorting Out Sections 284 and 285

Proving Non-Obviousness with Ex-Post Experimental Evidence?

The Vast Middle Ground of Hybrid Functional Claim Elements

STC.UMN v. Intel: Co-owners are necessary parties but may not be involuntarily joined

Court Affirms Inequitable Conduct for Inventor’s Failure to Submit Prior Art

Federal Circuit Defies Supreme Court in Laches Holding

Design Patents §103 – Obvious to Whom and As Compared to What?

Judge Bryson: Computerized Loyalty-Point Conversion System Not Patent Eligible

Judge Mayer Raises 101 When Not In Issue: Other Panelists Don’t

Federal Circuit affirms Rule 12 dismissal of a design patent case

Guest Post By Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

Anderson v. Kimberly-Clark Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2014) (nonprecedential)

Panel: Prost, Clevenger, Chen (per curiam)

In this case, pro se plaintiff Anderson alleged that nine different disposable undergarments infringed U.S. Patent No. D401,328 (the “D’328 patent”). Kimberly-Clark moved for judgment on the pleadings, asserting that it only manufactured five of the nine accused products—and none of those five infringed the D’328 patent. In a per curiam opinion released only two days after the case was submitted to the panel, the Federal Circuit agreed.

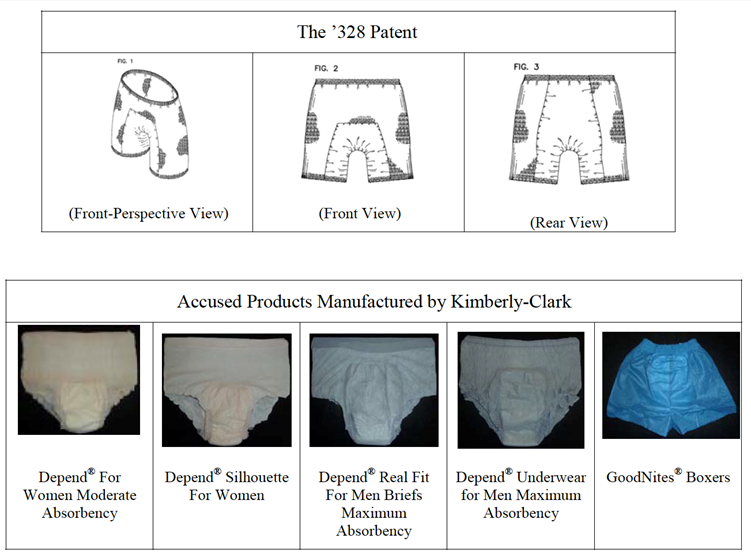

Under Egyptian Goddess, a design patent is infringed if “an ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art designs, would be deceived into believing that the accused product is the same as the patented design.” As these illustrations from Kimberly-Clark’s motion for judgment on the pleadings show, the accused products manufactured by Kimberly-Clark do not even arguably look “the same” as the patented design:

Indeed, in opposing Kimberly-Clark’s motion, Anderson did not even argue that the designs looked alike. And on appeal, her main argument was that the district court erred in considering the images shown above because they were not attached to her complaint. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, concluding that the district court did not err in considering the images because: (1) Anderson did not dispute their accuracy or authenticity; and (2) the appearances of the patent illustrations and accused products were integral to her claims. And ultimately, the Federal Circuit found no error in the District Court’s conclusion that Anderson had failed to state a plausible claim for infringement.

So this was a pretty easy case on the merits. And it is, of course, nonprecedential. But it’s still noteworthy because of its procedural posture. Since Egyptian Goddess, a number of courts have granted summary judgment of noninfringement where, as here, the accused designs were “plainly dissimilar” from the claimed design. But Rule 12 dismissals are still rare. And dismissals pursuant to Rule 12(c) are even rarer. It will be interesting to see if cases like this inspire more defendants to seek dismissal of weak design patent claims at the pleading stage.