Tag Archives: Licenses

Nonpracticing Entity (CSIRO) Gets Injunction

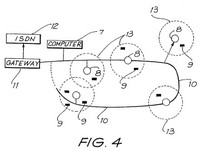

CSIRO operates as a technology licensing arm of the Australian Government. CSIRO does not practice its inventions, but has asserted its wireless LAN patent against a number of accused infringers, including Intel, Microsoft, Marvell, and Buffalo. The patent is broad enough to cover all 802.11a/g wireless technology and has a 1992 priority date.

In the case against Buffalo, CSIRO won a slam-dunk summary judgment of validity and infringement. The court then considered whether to award a permanent injunction in favor of the non-practicing entity (NPE).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Monsanto v. McFarling: CAFC Affirms “Reasonable Royalty” of 140% of Purchase Price

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patent Reform 2007: Apportionment of Damages

Patent are business tools that can help ensure some monetary reward for innovative effort. Although few patent are litigated through final decision, the threat of litigation casts an ever-present shadow on licensing negotiations and inter-corporate dealings. Of course, any underlying threat is closely related to the size of potential damages and strength of a potential injunction. In the past two-years, damages in particular have become more important as the Supreme Court's decision in EBay v. MercExchange lessens the likelihood of injunctive relief.

There has been little scholarly discussion of how ongoing money damages should be assessed when an injunction is denied. I take the position that a denial of an injunction should not necessarily result in a compulsory license and that there are many times when continued infringement would be considered willful.

The Patent Reform Acts of 2007 (both House and Senate) propose changes to damage calculations that would require specific economic analysis to ensure that any reasonable royalty damage award captures "only [the] economic value properly attributable to the patent's specific contribution over the prior art." These calculations would apparently apply to calculations of both past and future damages. CAFC Chief Judge Michel recently testified before Congress -- discussing some practical implementation of the damage modifications:

[T]he provision on apportioning damages would require courts to adjudicate the economic value of the entire prior art, the asserted patent claims, and also all other features of the accused product or process whether or not patented. This is a massive undertaking for which courts are ill-equipped. For one thing, generalist judges tack experience and expertise in making such extensive, complex economic valuations, as do lay jurors. For another, courts would be inundated with massive amounts of data, requiring extra weeks of trial in nearly every case. Resolving the meaning of this novel language could take years, as could the mandating of proper methods. The provision also invites an unseemly battle of "hired-gun" experts opining on the basis of indigestible quantities of economic data. Such an exercise might be successfully executed by an economic institution with massive resources and unlimited time, but hardly seems within the capability of already overburdened district courts. Appellate issue would also proliferate increasing complexity and delays on appeal, not to mention the risk of unsound decisions.

I am unaware of any convincing demonstration of the need for either provision, but even if the Committee ultimately concludes that they would represent an improvement over current patent policies embedded in Title 35 of the United States Code, their practicality seems to me very dubious. That is, the costs in delay and added attorneys fees for the parties and overburden for the courts would seem to outweigh any potential gains. Finally, even if the policy gains were viewed as significant, the courts as presently constituted simply cannot implement the provisions in a careful and timely manner, in my judgment.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patently-O TidBits

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

2007 Patent Reform: Proposed Amendments on Damages

The proposed 2007 Patent Reform Act (the “Leahy-Berman bill”)[1] details modifications to 35 USC § 284 that will most certainly reduce many patent infringement damages awards. Three portions of the Leahy-Berman bill concern monetary compensation: First, the bill seeks to limit reasonable royalty damages to the inventive aspects of the claim. Second, the bill restricts the use of the entire market value rule. Third, the bill expressly confirms a fact finder’s ability to rely on certain types of evidence to measure compensatory harm.[2]

Reasonable Royalty: Relationship to Contribution over the Prior Art and Consideration of Relevant Factors.

Perhaps the most striking change in the Leahy-Berman bill is a proposed limitation to reasonable royalty recovery. Under current law, a reasonable royalty is calculated by envisioning the result of the parties’ hypothetical negotiation for a license to the claimed invention at the time infringement began.[3] This determination is made by a fact finder (whether judge or jury) and is guided by the application of the Georgia Pacific fifteen-factor test.[4]

Current patent law permits a reasonable royalty calculation for use made of “the invention”—that is, an infringed claim. Of course, few--if any--patent claims are entirely novel. Most claims are an improvement over the prior art. Further, combination claims aggregate prior art elements in a novel way, or else a combination of novel elements together with prior art elements.

The Leahy-Berman bill specifically requires a limit on reasonable royalty recovery to the “economic value properly attributable to patent’s specific contributions over the prior art,”—that is, the inventive portion of the claim. Such an aggressive limit on monetary relief for patent infringement has not been apparent in the case law for decades.[5] A statement by Sen. Leahy (link) explains that this limitation is intended to provide for compensation solely for “the truly new ‘thing’ that the patent reflects,” in response to a concern that “litigation has not reliably produced damages awards in infringement cases that correspond to the value of the infringed patent.” This reasonable royalty limitation, which is likely to affect patents in all technology sectors, promises to be controversial.

Additionally, the Leahy-Berman bill asks trial courts to exercise more control over the fact finder’s consideration of the reasonable royalty and to create a more defined record for appellate review. Under current law, a typical reasonable royalty jury instruction lists all fifteen Georgia Pacific factors although fewer than all factors may be relevant in any particular case.[6] Further, a verdict form asks a jury to set a royalty figure, but jurors are rarely asked to create a record as to how their result was reached.

Under the Leahy-Berman bill, the trial court must “identify all factors relevant to the determination of a reasonable royalty” and then the fact finders are limited to consider only the factors identified by the district court in awarding a reasonable royalty. As an example of this provision in operation, a trial court might make an initial determination as to whether derivative or convoyed sales exist, such that the sixth factor of the Georgia Pacific test is relevant. If no such sales are in evidence, under the Leahy-Berman bill a trial court must preclude a jury’s consideration of this sixth factor.

Significantly, the proposed legislation’s use of the word “factors” does not appear to be limited to the Georgia Pacific factors specifically and presumably would apply to any factor that might be considered, including those listed in proposed section 284(a)(4).

Apportionment: The Entire Market Value Rule

As a general rule, patent damages are linked to the subject matter of the invention.[7] In some cases, an infringed claim relates to only one part of an entire multi-functional infringing product or system. In those circumstances, apportionment is the general rule—that is, damages are based on either lost profits or reasonable royalty apportioned for the infringing part as distinct from the remainder of a device that is outside the infringed claim’s scope. For example, damages for a claim directed to an improved windshield wiper are calculated based on the value of the infringing wiper, and not the sales price of the entire car into which the wiper is installed.

This general rule is modified under the judicially created “entire market value rule.” Where the entire market value rule applies, a patentee may recover damages based on the value of an entire apparatus or system that contains both infringing and additional, unpatented features.[8]

In “Let the Games Begin, Incentives To Innovation In The New Economy Of Intellectual Property Law,” I examine how the entire market value rule has recently received expansive application. Historically, the entire market value rule allowed recovery based on the price of entire product only where the “entire value” of the product was attributable to the infringing feature.[9] However, more recently, Federal Circuit cases more broadly apply the entire market value rule so long as there is a “functional relationship” between the infringing and the non-infringing components.[10] Further, patentees can recover for sales of non-infringing components where the patentee demonstrates a “reasonable probability” of selling the non-infringing components with the infringing part.[11]

An example of this expansive application of the entire market value rule can be seen in Lucent v. Newbridge Networks[12], where the district court determined that the jury’s addition of two software programs were properly included in the royalty base even where those programs were non-infringing, were not physically part of the infringing device and were not necessary for the device to operate. More recently, the Alcatel-Lucent verdict against Microsoft concerning the Windows® Media Player was reportedly calculated based on the average cost of a personal computer, and not limited to Microsoft’s Media Player or even Windows®.[13]

The Leahy-Berman bill provides an explicit, definitional standard for the application of the entire market value rule by requiring the patentee to show that the claim’s contribution is “the predominant basis for market demand” of an entire product or process. This standard reigns in the current expansive articulations of the entire market value rule by requiring a patentee to demonstrate that an infringing feature is the single primary reason users select an infringing product or process. If enacted, this subsection will have the overall effect of limiting damages to a particular infringing piece of a multifunctional product or process for both lost profits and reasonable royalty awards.

An open question exists as to the interaction between the proposed subsection (a)(2) governing reasonable royalties and (a)(3) governing the entire market value rule. Specifically, proposed subsection (a)(2) precludes recovery for the value of unpatented features of an infringing product or process. On the other hand, proposed subsection (a)(3) arguably permits such compensation where the inventive element is the “predominant basis for market demand.”

Marketplace Licensing and “Other Factors”.

The Leahy-Berman bill proposes one additional change, which appears of minor importance. That is, the bill expressly states that a fact finder may consider “the terms of a non-exclusive marketplace licensing of the invention” and any “other relevant factors” under the law in the damages determination. This subsection appears to be a codification of the existing law, which permits district courts wide discretion in considering evidence relevant to the damages determination.

Conclusion

As a whole, the Leahy-Berman bill represents an effort to refine and narrow available damages for patent infringement by building on an existing body of case law. The proposed changes to patent damages will undoubtedly present some challenging questions if adopted into law.

Two of the proposed sections require apportionment of inventive claimed matter from that outside the claim scope. The difficulty presented is that apportionment determinations can be difficult to implement. Perhaps the best evidence of this is the pre-1948 law, which relied on apportionment for calculating lost profits and had been described as a “complete failure of justice in almost every case in which supposed profits are recovered or recoverable” due to the time and complexity involved.[14]

Further, the Leahy-Berman bill has the potential for significant consequences for the licensing value of patents more generally. That is, to the extent that licensing determinations may reflect of potential results at trial, one might be expect that licensing negotiations will account for lowered damages the bill is passed into law. 2001).

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Antitrust Enforcement and Intellectual Property Rights: FTC/DOJ Joint Report

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patent Exhaustion at the Supreme Court

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Verizon v. Vonage

Vonage is the darling of network neutrality advocates. Using Vonage, millions of people have canceled their telephone service in favor of an IP-phone that connects through the Internet.

Last month, a jury determined that Vonage infringed three Verizon patents. (6,282,574, 6,104,711, 6,359,880). These patents all relate to various aspects of Internet telephony.

This is not a "troll" case -- By definition, patent trolls are only looking for a payment in exchange for a patent license. Here, it is fairly clear that Verizon hopes that its patents will cause Vonage to close its doors. Thus, Verizon requested and was granted a permanent injunction.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Teva v. Novartis: Generic Declaratory Judgment Actions

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

USPTO Public Pair: Static URLs Please

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC Expands Scope of Declaratory Judgment Jurisdiction

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Patent Attorneys: Ethics of Representing Out-of-State Clients

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Enhanced Damages: No ‘Prevailing Party’ after Rule 41(a) Voluntary Dismissal

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Microsoft v. AT&T: Unlicensed Export of Patented Software

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Wegner: Escaping the Depths of the Patent Shadows

A response to Merges, By Hal Wegner

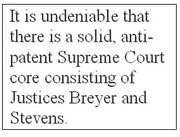

Professor Robert P. Merges makes much sense in his op-ed piece, Back to the Shadows, or Onward and Upward? Current Trends in Patent Law. We and thoughtful supporters of the patent system share much common ground. Professor Merges touches on numerous points where there is hardly any significant difference with this writer, including the domestic results of the eBay decision from last year. In his analysis of the Supreme Court, Professor Merges is correct that the Court is generally “pro business”, but it is another matter whether in some industries being “pro business” means being “pro-patent”.

Feeding this nascent anti-patent core are two dominant themes: First, while the Supreme Court is pro-business, a major segment of the business community is largely anti-patent, turning the patent system upside down: Under this twisted view of patents, being “anti-patent” may be “pro business”. Second, the patent jurisprudence of the Federal Circuit has created and continues to create problems that necessarily fuel further growth of an anti-patent sentiment.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

CAFC: Prior suit against manufacturer precluded later suit against end users

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

“Right-to-Sue” Clause Does Not Give Licensee a Right to Sue

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Even under DOE, “predetermined” combo must be determined beforehand

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.

Parallel Finding of Invalidity Did Not Relieve Licensee’s Pressure to Pay Royalties for Urinary Catheter Patent

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.