Tag Archives: Licenses

Tesla’s Patents are Your Patents

Patent Reform 2014: Removing Non-Practicing Entities from the USITC’s Jurisdiction

Supreme Court: In Copyright, Laches Cannot Preclude Actions Taken Within Three Year Statute of Limitations

Kelley Drye Misses First Step in Collecting $14 Million Fee from Client

Fee Shifting in the Future

Guest Post: Are APIs Patent or Copyright Subject Matter?

Spouses of Inventors as Co-Owners

Opportunity Lost: Economic Analysis in Apple v. Motorola

Federal Circuit: Jury Must Award Damages for Infringement

Proving Obvious with Post-Filing Evidence?: Yes

Preliminary Injunction Can Issue Even Though Patentee Does not Practice the Invention

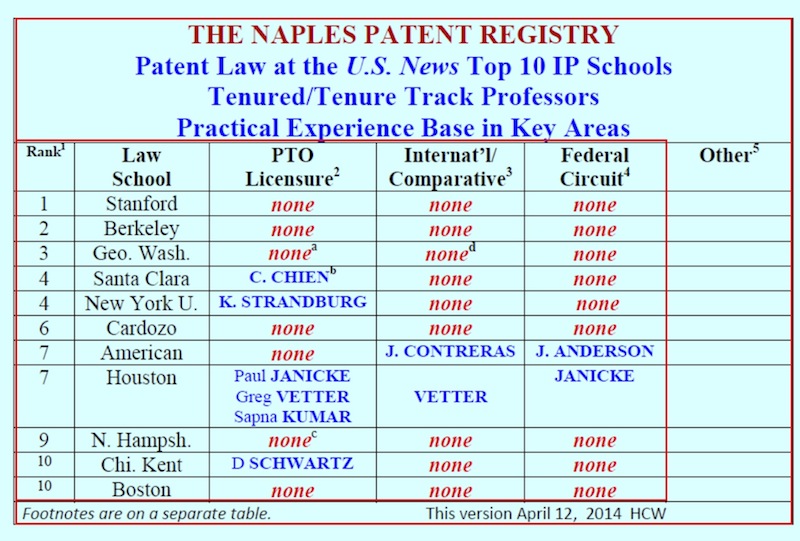

Guest Post by Prof. Sichelman: Stop Bashing Academics: Why Mark Lemley, Peter Menell, and Rob Merges are Highly Qualified to Teach and Write about Patent Law

Design patent nonobviousness jurisprudence — going to the dogs?

Guest post by Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

MRC Innovations, Inc. v. Hunter Mfg., LLP (Fed. Cir. April 2, 2014) 13-1433.Opinion.3-31-2014.1

Panel: Prost (author), Rader, Chen

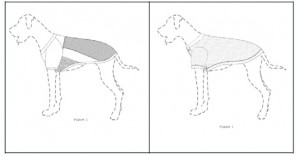

MRC owns U.S. Patent Nos. D634,488 S (“the D’488 patent”) and D634,487 S (“the D’487 patent”). Both patents claim designs for sports jerseys for dogs—specifically, the D’488 patent claims a design for a football jersey (below left) and the D’487 patent claims a design for a baseball jersey (below right):

Mark Cohen is the principal shareholder of MRC and the named inventor on both patents. Hunter is a retailer of licensed sports products, including pet jerseys. In the past, Hunter purchased pet jerseys from companies affiliated with Cohen. The relationship broke down in 2010. Hunter subsequently contracted with another supplier (also a defendant-appellee in this case) to make jerseys similar to those designed by Cohen.

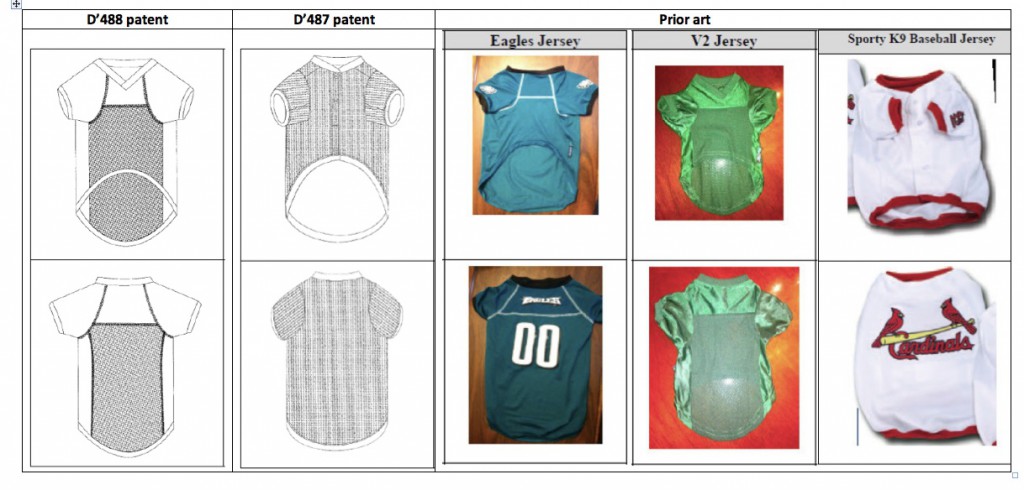

MRC sued Hunter and its new supplier for patent infringement. The district court granted summary judgment to the defendants, concluding that the patents-in-suit were invalid as obvious in light of the following pieces of prior art:

Step One – Primary References

On appeal, MRC argued that the district court erred in identifying the Eagles jersey as a primary reference for the D’488 patent. The Federal Circuit disagreed, stating that either the Eagles Jersey or the V2 jersey could serve as a proper primary reference for the D’488 patent.

MRC also argued that the Sporty K9 jersey could not serve as a proper primary reference for the D’487 patent. Again, the Federal Circuit disagreed, stating that the Sporty K9 jersey had “basically the same” appearance as the patented design.

Step Two – Secondary References

In its analysis, the district court used the V2 jersey and Sporty K9 jersey as secondary references for the D’488 patent and the Eagles jersey and V2 jersey as secondary references for the D’487 patent. On appeal, “MRC argue[d] that the district court erred by failing to explain why a skilled artisan would have chosen to incorporate” features found in the secondary references with those found in the primary references. The Federal Circuit did not agree, stating that:

It is true that “[i]n order for secondary references to be considered, . . . there must be some suggestion in the prior art to modify the basic design with features from the secondary references.” In re Borden, 90 F.3d at 1574. However, we have explained this requirement to mean that “the teachings of prior art designs may be combined only when the designs are ‘so related that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.’” Id. at 1575 (quoting In re Glavas, 230 F.2d 447, 450 (CCPA 1956)). In other words, it is the mere similarity in appearance that itself provides the suggestion that one should apply certain features to another design.

The Federal Circuit noted that in Borden, it found that designs for dual-chambered containers could be proper secondary references where the claimed design was also directed to a dual-chambered container. And in this case, “the secondary references that the district court relied on were not furniture, or drapes, or dresses, or even human football jerseys; they were football jerseys designed to be worn by dogs.” Accordingly, the Federal Circuit concluded that they were proper secondary references.

Secondary Considerations

MRC also argued that the district court failed to properly consider its evidence of commercial success, copying and acceptance by others. The Federal Circuit disagreed, concluding that MRC had failed to meet its burden of proving a nexus between those secondary considerations and the claimed designs.

Comments

The Federal Circuit hasn’t actually reached the second step of this test in a while. That’s because it has been requiring a very high degree of similarity for primary references (see High Point & Apple I). For a while there, it looked like it was becoming practically impossible to invalidate any design patents under § 103. Now we at least know that it’s still possible.

But we don’t have much guidance as to when it’s possible. In particular, it’s difficult to reconcile the Federal Circuit’s decision on the primary reference issue with its decision in High Point. The Woolrich slipper designs that were used as primary references by the district court in High Point were, at least arguably, as similar to the patented slipper design as the Eagles and Sporty K9 jerseys are to MRC’s designs. But in High Point, the Federal Circuit suggested that there were genuine issues of fact as to whether the slippers were proper primary references.

And unfortunately, the Federal Circuit seems to have revived the ill-advised Borden standard. As I’ve argued before, the second step of the § 103 test has never made much sense. Even the judges of the C.C.P.A., the court that created the test, had trouble agreeing about how it should be applied. But the Borden gloss—that there is an “implicit suggestion to combine” where the two design features that were missing from the primary reference could be found in similar products—is particularly nonsensical. At best, this Borden-type evidence suggests that it would be possible to incorporate a given feature into a new design, from a mechanical perspective—not that it would be obvious to do so, from an aesthetic perspective.

All in all, this case provides an excellent illustration of the problems with the Federal Circuit’s current test for design patent nonobviousness. Perhaps now that litigants can see that § 103 challenges are not futile, the Federal Circuit will have opportunities to reconsider its approach.