Tag Archives: Written Description

CAFC Written Description Jurisprudence: “OPAQUE”

Supreme Court: LabCorp Briefing Round I [UPDATED]

Patently-O Blog: Terms of Use

Under 102(g), Conception of Prior Art Requires Appreciation of Invention

LabCorp v. Metabolite: Supreme Court To Hear Patent Case Questioning Patentability Of Medical Method

Single Embodiment Of Claim Element Fails To Describe Element Generically

Assignor Estoppel: Inventor barred from testifying for defense

Nystrom v. Trex: Take Two

Claim Construction: Specification is Always Highly Relevant

Federal Circuit: Nucleotide Sequence of Claimed DNA not Required to Satisfy Written Description Requirement

Written Description Does Not Require Explicit Disclosure of Claim Terms

PTO Board: Disclosure of Sequence Enables at least 5% of Natural Variance.

Indecipherable Patents

Blade Wars: Gillette Wins Latest Round in Multi-Blade Razor Patent Litigation

Gillette’s patent disclosing a three-blade razor also covers a four-blade version.

Gillette Co. v. Energizer Holdings Co. (Fed. Cir. 2005).

By Baltazar Gomez

Gillette owns U.S. Patent No. 6,212,777 for wet-shave safety razors with multiple blades. Gillette sued Energizer in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts alleging Energizer’s QUATTRO®, a four-bladed wet-shave safety razor, infringed claims of the patent. The district court denied Gillette’s motion for a preliminary injunction because it found that the claims covered only a three-bladed razor. On appeal, CAFC vacated the district court’s decision and remanded for further proceeding.

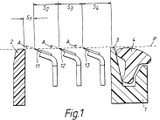

The ’777 patent claims a disposable safety razor with a group of blades, each blade placed in a particular geometric position relative to the other blades. Claim 1 describes a progressive blade exposure as follows:

A safety razor blade unit comprising a guard, a cap, and a group of first, second, and third blades with parallel sharpened edges located between the guard and cap… (emphasis added).

In determining the meaning and the scope of claim 1, the CAFC attempted to place the claim language in its proper technological and temporal context. The Court reasoned that the inventors’ statutorily-required written description in the patent itself, including the claims, the specification and the prosecution history, is the primary source of the meaning of disputed claim language.

Using this standard, CAFC determined that the language “comprising . . . a group of first, second, and third blades” can encompass the four-bladed Energizer razors. To begin, CAFC noted that the claim uses “open” claim terms “comprising” and “group of” in addition to other language to encompass subject matter beyond a razor with only three blades. Moreover, although the specification focused on blade units with three blades, the patent also disclosed a plurality of blades showing that the ‘777 patent covers razors with more than three blades. The CAFC further explained that it may be that a four-bladed razor may be less preferred embodiment, but noted that a patentee typically claims broadly enough to cover less preferred embodiments as well as more preferred embodiments, precisely to block competitors from marketing less than optimal versions of the claimed invention.

Further, CAFC also noted that the specification provided further support for interpreting claim 1 to encompass razors with more than three blades. The first sentence of the written description teaches that the invention relates to razors having a plurality of blades. Moreover, the prosecution of patents related to the ’777 patent also supports reading claim 1 as an open claim. Gillette endorsed an open interpretation of “comprising” when it argued to the European Patent Office (EPO) that a virtually identical claim in Gillette’s European counterpart to the ’777 patent would not exclude an arrangement with four or more blades. Accordingly, the CAFC concluded that the district court erred in limiting the claims of the ’777 patent to encompass razors with three blades because no statement in the ‘777 patent excludes a four-bladed razor.

In dissent, Judge Archer argued that claim 1 should not be construed as permitting a group with more than three blades simply because claim 1 contains the open transition term “comprising” in its preamble. Judge Archer concluded that a three-bladed razor is not merely a preferred embodiment of the invention, but is the invention itself, and that the inventors did not regard a blade unit with four blades arranged in the described geometry as their invention.

Note: Dr. Baltazar Gomez is a scientific advisor at MBHB in Chicago. Dr. Gomez obtained his PhD in biochemistry from the University of Texas and researched retrovirology as a PostDoc at Cornell University.

Written Description: Defendant’s Own Expert Deposition Testimony Used to Overturn Summary Judgment of Invalidity

By John Smith

Loral, the owner of U.S. patent 4,537,375 (the ‘375 patent), sued Lockheed for infringement of claim 1. The District Court ruled in favor of Lockheed, finding the claim invalid for violating the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112.

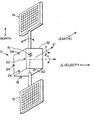

The ‘375 patent is directed to an improved method for maintaining the orientation and attitude of a satellite in space by a process known as station-keeping. After an initial thrust, the satellite re-checks its position, and often fires its thrusters again to better correct its position. Station-keeping thus uses the limited fuel supply on board a satellite and contributes to shortening the life of satellites. The ‘375 patent discloses a method directed to improving the efficiency of the corrective procedure.

Claim 1 of the ‘375 patent entails a multi-step procedure of thruster-firing, data storage, checking of position and correction of position, and minimization of error in correction of position. Essentially, the satellite fires its thrusters to correct its position, then checks its position and compares its current error in position to its previous error in position before firing its thrusters again. Lockheed argued that the patent was invalid, because the second step of claim 1 was not adequately described in the specification.

Defendant Lockheed’s expert, when asked at deposition where one would find the second step description, answered (over counsel objections) that the second step was depicted in Item 96 of Figure 2B. The court found this, along with the testimony of plaintiffs’ expert, established that the specification sufficiently described the claim.

Lockheed also argued that the second step of claim 1 was not inherent in the written description because the specification did not state that the second step was necessarily used in the satellite position correction procedure. On appeal, the Federal Circuit noted that the second step of the claim at issue in the procedure comes only (if at all) after thrusters are fired and actual position error and historical position error are compared. According to the Federal Circuit, this “does not diminish the descriptive content of the specification.”

The Federal Circuit reversed the finding of invalidity, and remanded back to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California for further proceedings.

John Smith is an attorney at MBHB LLP in Chicago. He earned both his JD and PhD (inorganic chemistry) from Vanderbilt University. He has co-authored numerous articles and served as a faculty member in the Chemistry Department of Lipscomb University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Notes:

-

In his Case Alert, David Long of the Howrey firm correctly noted that this case should be “kept in mind by litigators taking or defending technical expert depositions on written description issues.”

It is proper to limit the scope of the claims according to the specification

By Baltazar Gomez, Ph.D.

Rhodia is an international chemical company and the assignee of U.S. Pat. No. 6,013,234 (“the ‘234 patent”). The patent discloses and claims certain essentially spheroidal precipitated silica particulates. Rhodia markets “Micropearl” which is a silica particulate covered by the patent. PPG also makes three silica products, namely, Hi-Sil SC60M, SC72 and SC72C. Rhodia alleges that these products infringe claim 1 of the ‘234 patent.

The district court granted summary judgment for noninfringement in favor of PPG. On appeal, Rhodia argued that the district court erred in interpreting claim 1. The CAFC, however, affirmed the district court’s construction.

Claim 1 of the ‘234 patent partly reads as follows: Dry, dust-free and non-dusting, solid and homogeneous atomized precipitated silica particulates essentially spheroidal in geometrical configuration… (emphasis added)

In addition, the specification included examples tested both for flowability and dusting properties. Flowablity tests were performed by a pour test which compared the flowability of Micropearl with the prior art. The dusting tests were measured by the German DIN 53 583 standard (the “DIN test”).

During the district court’s claim construction hearing, PPG asserted that the phrase “dust-free and non-dusting” should be interpreted literally to mean “no dust cloud whatsoever.” Conversely, Rhodia argued that such a meaning was improper in view of the results of the pour test that showed production of some dust. Accordingly, Rhodia advocated construing “dust-free and non-dusting” to mean “very low dust.”

The district court was concerned, however, that Rhodia’s proposed definition of the phrase was relative and that such a definition would not meet the statutory requirement that the claims particularly point out and distinctly claim the invention. Thus, to resolve the perceived ambiguity of the phrase, the district court adopted a construction based upon the only meaningful guidance provided in the patent, namely the DIN test.

On appeal, Rhodia argued that the DIN test was not the only means by which to assess the amount of dust produced by the invention. Rhodia asserted that the pour test could also be used to determine the level of dustiness, and therefore, it is inappropriate for the district court to limit the phrase “dust-free and non-dusting” to the DIN test. Further, Rhodia cited statements made during prosecution of the ‘234 patent explaining that the pour test could be used to show the non-dusting and free-flowing properties of the ‘234 patent.

In affirming the district court’s construing of “dust-free and non-dusting”, CAFC noted that although the pour test may also provide evidence of dustiness, the results of the pour tests presented in the ‘234 patent were only identified as evidence of the products’ flowability. The CAFC further noted that there is no language in either the claims or the written description that taught the application of the pour test to determine the level of dustiness. Finally, CAFC stated that Rhodia’s statements made during prosecution cannot serve to fill such a gap. Thus, the CAFC concluded that the district court did not erred in limiting the scope of the claims by defining the phrase “dust-free and non-dusting” to the only disclosure in the patent.

Note: Dr. Baltazar Gomez is a scientific advisor at McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP in Chicago. Dr. Gomez obtained his PhD in biochemistry from the University of Texas and researched retrovirology as a PostDoc at Cornell University.

March 2005 Report on New Academic Research

Each month I post a note discussing new research from the academic side of patent law. This March edition includes three great articles that relate to either legislative changes (prior use statute, post grant opposition) or upcoming court decisions (Phillips claim construction case). Feel free to e-mail suggestions for April’s edition.

- Tom Fairhall and Paul Churilla, Prior Use of Trade Secrets and the Intersection with Patent Law, 14 Fed. Cir. Bar J. 455. Fairhall and Churilla present a timely article on prior use rights that notes how the current prior use statute (35 USC 273) does not provide the scope necessary to truly protect a prior user’s expectations or investments. The article is quite timely because FTC proposals to expand the statutory prior use rights is gaining some teeth in the patent community and on the Hill.

- Mark Lemley, The Changing Meaning of Patent Claim Terms, available at SSRN. Professor Lemley’s article is also timely — he discusses at what particular point in time should the meaning of claim terms be fixed. This is important because the ordinary meaning of terms in the English language change over time. The major temporal candidates are (i) at the time of the invention (currently used for novelty and nonobviousness); (ii) at the time the application was filed (currently used for enablement or written description); (iii) a the time the patent issues (currently used for means-plus-function claim construction); and (iv) at the time of the infringement (at least some times used to determine infringement). Lemley agrees that each candidate has a sound legal foundation. However, he argues that the best approach moving forward is to fix the meaning at the time the patent application is first filed.

- Jay Kesan and Andres Gallo, Why ‘Bad’ Patents Survive in the Market, available at SSRN. The professors provide a game theory model to show how would-be invalid patents can survive and be valuable in the marketplace. Essentially, the transaction costs make it difficult to mount an effective challenge to improperly granted patents. Their work will serve as the theoretical basis any proposed post-grant opposition procedures. Specifically, the authors “conclude that a low-cost, post-grant opposition process based primarily on written submissions within a limited estoppel effect . . . will serve as an effective instrument for improving the quality of patents that are issued and enforced.”

Snippets: Review of Developments in Intellectual Property Law

MBHB’s snippetsTM newsletter provides a timely review of developments in intellectual property law. Here is a table of contents of the most recent issue (March 2005: Volume 3, Issue 1):

- Daniel Boehnen and Deana Larkin, Trends in E-Discovery: New Local Rules and Recent Judicial Opinions.

- Michael Greenfield, Jennifer Pope, Dennis Crouch, and Elaine Chang, The Primary Source for Claim Construction: Dictionary or Specification.

- Kevin Noonan, The Continued Confusion Over Written Description.

- Dennis Crouch and Baltazar Gomez, Legislative Update: Joint Research Agreements May Protect Patent Rights.

You can e-mail the editor (snippets@mbhb.com) to receive a PDF copy of the newsletter. Include your mailing address if you would like a hard-copy. In the e-mail, please indicate your technology and legal interest: (Biotech, Electrical, Software, Chemical, Mechanical, Litigation, and/or Prosecution).

Past Issues:

CAFC: Ordinary Meaning Defined By Context of Written Description

Medrad filed suit against MRI Devices for allegedly infringing Medrad’s patented radio frequency (RF) coils used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The district court granted a partial summary judgment of invalidity after construing the claims of the patent.

On appeal, the CAFC struggled to give meaning to a claim that “itself provides little guidance.”

Interpreting the term “substantially uniform,” the court rejected Medrad’s argument that the “court may not look to how an invention functions in determining the meaning of claim terms” — finding that proposition “as unsound as it is sweeping.”

We cannot look at the ordinary meaning of the term . . . in a vacuum. Rather, we must look at the ordinary meaning in the context of the written description and the prosecution history. Quoting DeMarini Sport (Fed. Cir. 2001).

Basing its decision on (1) claim language, (2) the specification, and (3) expert testimony, the appellate court found that “substantially uniform” in reference to a magnetic field meant that the magnetic field is sufficiently uniform to obtain useful MRI images.

Affirmed.

Ex parte Bandman, No. 2004-2319, (BPAI 2005)

Ex parte Bandman, No. 2004-2319, (BPAI 2005)