by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit has ruled that Crown Packaging's high-speed necking machine patents are invalid under the pre-AIA on-sale bar, reversing a Virginia district court's summary judgment decision. Crown Packaging Technology, Inc. v. Belvac Production Machinery, Inc., Nos. 2022-2299, 2022-2300 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 10, 2024). The court held that a detailed price quotation marked "subject to written acceptance" can still constitute an invalidating offer for sale and not merely an invitation to make an offer.

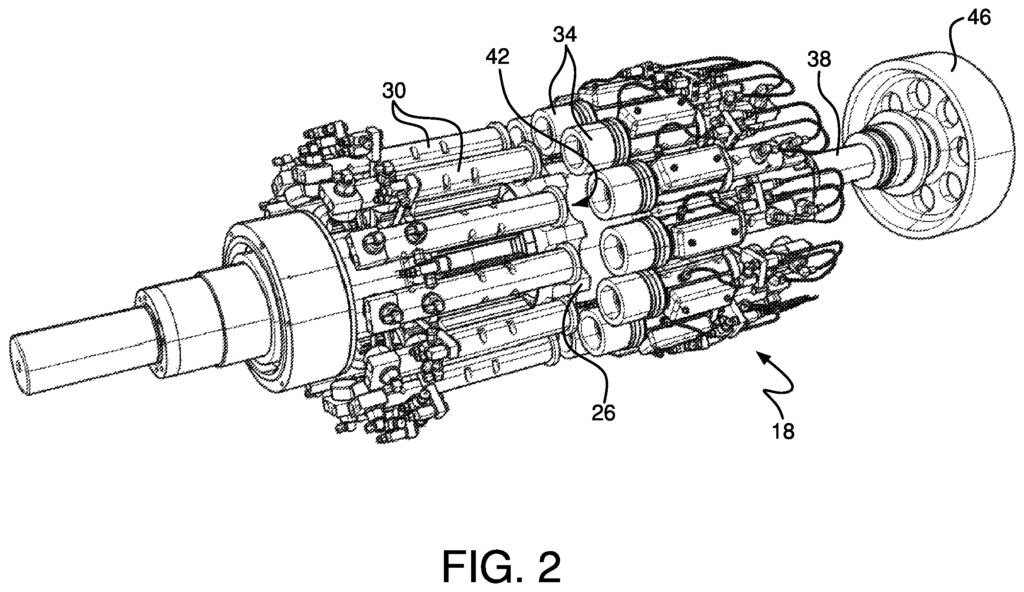

Ooh la la ... high speed necking. For those wondering, "necking" in the beverage can industry refers to the manufacturing step of reducing a can's diameter at the top to create the tapered shape we drink from. Crown's patents at issue in the case (U.S. Patent Nos. 9,308,570; 9,968,982; and 10,751,784) protect their horizontal, multi-stage necking machines designed for such high-speed production.