By Jason Rantanen

STC.UMN v. Intel Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2014)

Original panel: Rader (author), Dyk, Newman (dissenting)

Denial of rehearing en banc: Dyk, concurring (joined by Moore and Taranto); Newman, dissenting (joined by Lourie, O’Malley, and Wallach); O’Malley, dissenting (joined by Newman, Lourie and Wallach)

Panel opinion

Denial of rehearing en banc

The issue at the core of this appeal was whether a co-owner of a patent can be forced to join an infringement lawsuit brought by another co-owner or instead effectively block the suit by refusing to participate. The Federal Circuit is deeply split on this issue, as evidenced by both the June 2-1 panel opinion and the 6-4 refusal to rehear the decision en banc. The panel majority held that a co-owner may not be forced to join the infringement suit and because the full court denied rehearing en banc, that holding stands unless the Court grants cert. Judge Newman and Judge O’Malley both wrote dissenting opinions.

The patent right and co-owners. Co-owners of a patent may separately exercise all the rights of a patent owner: they may make, use, offer for sale, and import the patented invention without needing the permission of the other co-owner. They may also grant a license to the patent. Importantly, they may do all of this without giving the other co-owner a dime; unlike for copyrighted works, there is no right of accounting for patents.

A consequence of this is that if there are co-owners of a patent, a prospective infringer need only obtain a license from one co-owner. This makes unity of patent rights important for any party who wishes to actually enforce those rights as against future conduct.

This rule is clear as to future conduct; the complexity comes about when dealing with past infringing activities. A patent co-owner may only grant a prospective license to the patent and a release as to its own claims for liability for past infringing conduct; it may not release infringers from liability to the other co-owner for past infringement. However, it is also blackletter law that all owners of a patent must be parties to an infringement suit for there to be standing. But not all co-owners may cooperate with the party wanting to bring the suit. Perhaps they have some contractual obligation to the accused infringer; perhaps they are even directly connected to the accused infringer. Or perhaps, as in this case, the co-owner just wants to remain “neutral.” Does the uncooperative co-owner have the right to do so?

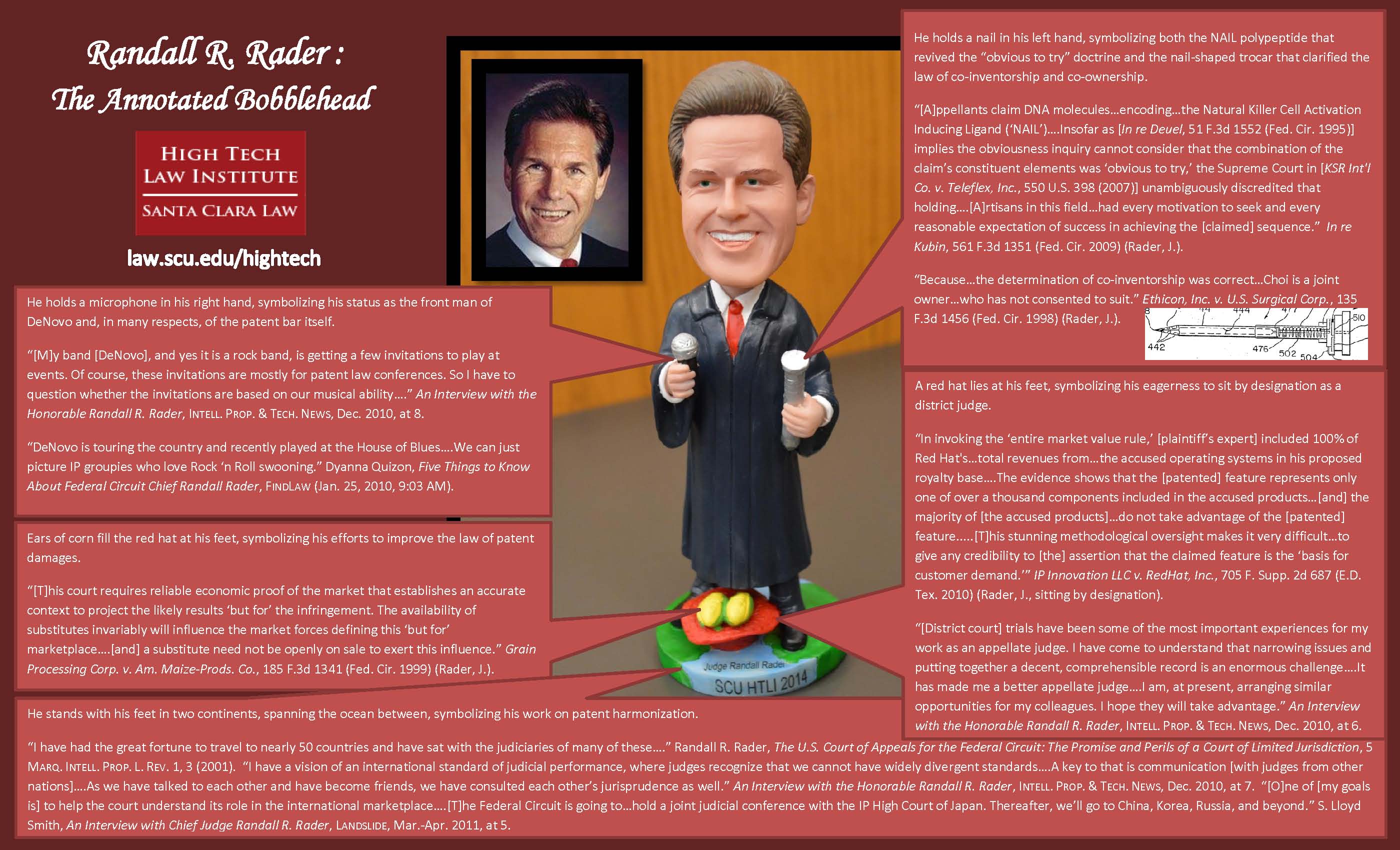

This case can be seen as an old fight renewed. The origins of the split go back to the Federal Circuit’s 1998 decision in Ethicon v. United States Surgical, 135 F.3d 1456. The majority opinion, written by Judge Rader, dismissed the suit on the ground that a co-owner could not and did not consent to the infringement. This conclusion followed the following statement of law:

Further, as a matter of substantive patent law, all co-owners must ordinarily consent to join as plaintiffs in an infringement suit.9 Consequently, “one co-owner has the right to impede the other co-owner’s ability to sue infringers by refusing to voluntarily join in such a suit.” Schering, 104 F.3d at 345.

Footnote 9 referred to two exceptions: where the co-owner has waived its right to refuse to join the suit and where there is an exclusive licensee, the exclusive licensee may sue in the owner’s name.

Judge Newman dissented in Ethicon. While much of her dissent focused on the issue of whether an inventor on only some of the claims is a co-owner of the patent as a whole (Judge Newman would have held no), she also pointed out that Rule 19’s involuntary joinder rule should apply here.

Involuntary Joinder Does Not Apply: Drawing heavily upon Ethicon, the panel opinion in this case – also written by Judge Rader -extended the rule that co-owners of a patent may refuse to voluntarily join an infringement suit to preclude operation of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 19(a). The relevant portion of that rule states:

(1) Required Party. A person who is subject to service of process and whose joinder will not deprive the court of subject-matter jurisdiction must be joined as a party if:

(A) in that person’s absence, the court cannot accord complete relief among existing parties; or

(B) that person claims an interest relating to the subject of the action and is so situated that disposing of the action in the person’s absence may:

(i) as a practical matter impair or impede the person’s ability to protect the interest; or

(ii) leave an existing party subject to a substantial risk of incurring double, multiple, or otherwise inconsistent obligations because of the interest.

(2) Joinder by Court Order. If a person has not been joined as required, the court must order that the person be made a party. A person who refuses to join as a plaintiff may be made either a defendant or, in a proper case, an involuntary plaintiff.

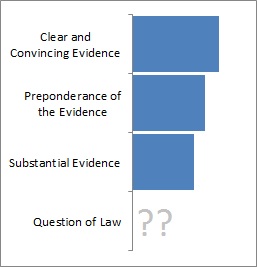

A few things to note: First, no one appears to be disputing that Rule 19 has the force of law or that a co-owner may refuse to voluntarily participate in a patent infringement suit. Rather, the disagreement boils down to (1) whether the co-owner has a “substantive right” not to participate in a patent infringement suit and (2) if there is such a right, whether it preclude the application of Rule 19.

Unfortunately, as Judge O’Malley’s dissent points out with particular rigor, the panel majority opinion is is quite short on the basis for this “substantive right.” The basic legal move the majority makes is to rely on precedent holding that a co-owner may refuse to voluntarily participate in a patent suit as providing the basis for a substantive right not to join an infringement suit, with the policy basis that the anti-involuntary joinder rule ” protects, inter alia, a co-owner’s right not to be thrust into costly litigation where its patent is subject to potential invalidation.”

Concurring in the denial of en banc review, Judge Dyk’s opinion fleshes out the argument in more detail. In Judge Dyk’s articulation, the question is whether there is a “substantive obligation” for the co-owner of a patent to join the suit; in the absence of a “substantive obligation,” the co-owner cannot be forced to join through the operation of procedural rules, such as Rule 19. Judge Dyk thus flips the question: while he points to cases where the co-owner did not consent, and thus the suit was dismissed, he also points out the lack of patent cases imposing a “substantive obligation on a patent co-owner to consent to the assertion of an infringement claim.” This allocation of substantive rights cannot be changed by application of Rule 19.

Writing in dissent to the denial of rehearing en banc, Judge O’Malley challenged both the basis for the substantive right as well as way such a “right” interacts with Rule 19. Walking through Ethicon and the other cases cited by Judges Rader and Dyk, Judge O’Malley challenges the precedential basis for such a “right.” Nor, Judge O’Malley argues, is there any basis in statute for this “right;” indeed, it is directly contradicted by other statutory “rights,” particularly Section 154(a)(1), “the right to exclude others.” And in any event, Rule 19 is *mandatory.* “By its terms, therefore, when a person satisfies the requirements of Rule 19(a), joinder of that person is required.”

So what’s going to happen? As Hal Wegner has noted in his email newsletter, a petition for certiorari is expected in this case. And, given that the core issue is one of civil procedure, albeit intertwined with an issue of the nature of the patent right, it may be particularly appealing for the Court – especially coupled with the deep split and thoughtful opinions of two of the Federal Circuit’s sharpest thinkers.

An odd issue raised by the majority rule here: What happens when one co-owner sends out threatening letters to an accused infringer but the other does not. Can the accused infringer bring a declaratory judgment action against both co-owners? If not, must the declaratory judgment action be dismissed for lack of standing? Or is this sufficiently different from an affirmative suit for infringement as to make the “all parties required” rule not apply?