By Ryan Abbott. Professor Abbott, MD, JD, MTOM, PhD, is Professor of Law and Health Sciences at the University of Surrey School of Law, Adjunct Associate Professor of Medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, partner at Brown, Neri, Smith & Khan, LLP, and a mediator and arbitrator with JAMS, Inc.

Recently, the Federal Circuit handed down its decision in Recentive v. Fox which the Court stated presented a question of first impression: “whether claims that do no more than apply existing methods of machine learning to a new data environment are patent eligible.” Recentive Analytics, Inc. v. Fox Corp., 134 F.4th 1205 (Fed. Cir. 2025). As the framing of the question suggests, the Court answered in the negative, confirming that patents that simply take an abstract idea and “do it with AI” are not statutory subject matter.

Since this decision, questions have come up about what this might mean for the patenting of inventions relating to artificial intelligence (AI) in the United States, and by extension, America’s leadership in AI development. Even before this case, the argument has been made that getting patents on AI innovations is difficult or impossible under the current law, and therefore patent eligibility reform is needed. These are important questions. As I have argued for years in my work on the Artificial Inventor Project, and as I testified on in Congress, AI technology is playing a rapidly growing role in the innovation process. We want to make sure the patent system is promoting the development and use of AI so that it can be used to generate socially valuable innovation (and that there are no legal concerns when that happens, including related to inventorship).

My view is that current patent eligibility law as it pertains to abstract ideas best supports the AI development and innovation that we need in the United States. The current approach permits the patenting of all aspects of AI technology – from the development and training of machine learning models to the applications of those models. Recentive gave us a glimpse into how patent eligibility law applies at one end of the AI patenting spectrum, and it reached the right conclusion.

Before delving into Recentive, it is helpful to understand the application of patent eligibility law in a traditional software patenting context. Eligibility analysis relies on the two-step Alice/Mayo test, which first determines whether claims are directed to judicial exceptions to eligible matter, namely abstract ideas, laws of nature, or natural phenomena. Alice Corporation v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014); Mayo Collab. Servs. v. Prometheus Lab’ys, Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012). If claims are directed to a judicial exception then to be patent eligible they must recite additional elements that amount to “significantly more” than the judicial exception. Mayo, 566 U.S. at 72-73. The Supreme Court has described the second part of the test as the search for an “inventive concept”. See MPEP § 2106. This is the Supreme Court’s way of ensuring that a true, technological invention lies at the heart of the patent and that it isn’t just an abstract idea dressed up to look like a real invention.

For more than a decade, the Alice/Mayo two-part test has been the exclusive test for software patent eligibility analysis. It balances patent incentives with the need to allow the public to utilize “the basic tools of scientific and technical work.” Alice Corp., 573 U.S. at 216. Patents on such tools could do more harm than good and “might tend to impede innovation more than it would tend to promote it.” Id. Claims are not ineligible simply because they involve judicial exceptions, the applications of such concepts remain protectable. Indeed, the Federal Circuit has subsequently clarified that claims directed to software and improvements in computer-related technologies are not inherently abstract. See, e.g., Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1335 (Fed. Cir. 2016); see also Visual Memory LLC v. NVIDIA Corp., 867 F.3d 1253, 1258 (Fed. Cir. 2017). Judicial exceptions have existed for more than 150 years, and a significant amount of case law has now applied Alice/Mayo in the context of software patents.

The Federal Circuit has tended to require patent applications to describe specific improvements over the prior art that improve a process, whether software- or hardware-based, rather than merely performing an existing process on a computer. This has allowed a wide range of computer-implemented claims to be found patent-eligible. See, e.g., McRO Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America Inc., 837 F. 3d 1299 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Amdocs (Israel) Ltd. v. Openet Telecom Inc., 841 F. 3d 1288 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Ancora Technologies Inc. v. HTC America Inc., 908 F. 3d 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2018). This standard thus encourages research and development into improvements in computer processes, while preventing applicants from broadly tying up the use of computers to perform existing processes and relying on functional claiming (e.g., filtering content on a computer, unless an improvement over the prior art for filtering content; parsing, editing, sorting, and comparing data, absent a specific inventive method for carrying out these functions). See BASCOM Glob. Internet Servs., Inc. v. AT&T Mobility LLC, 827 F.3d 1341, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2016); see Berkheimer v. HP Inc., 881 F.3d 1360, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

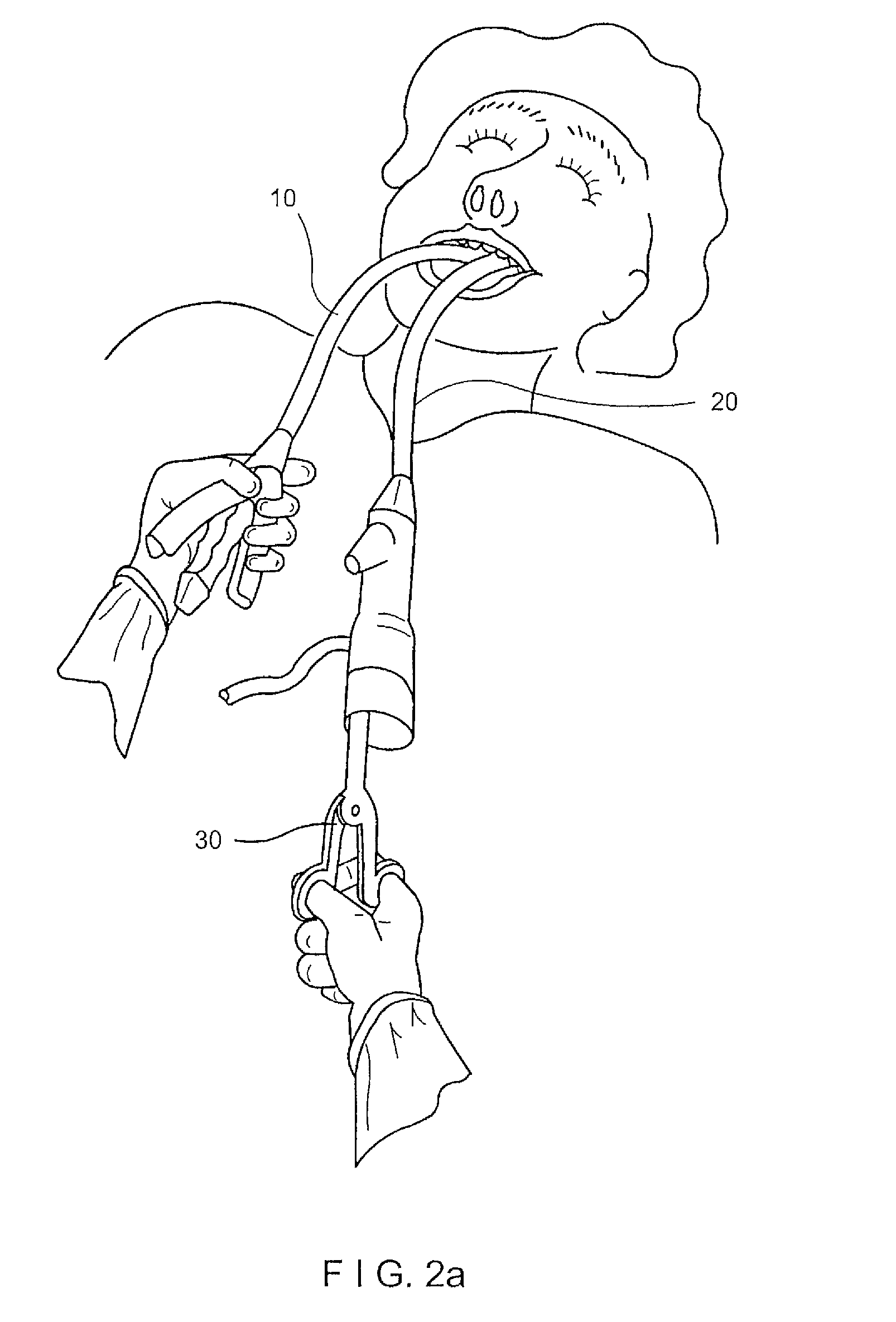

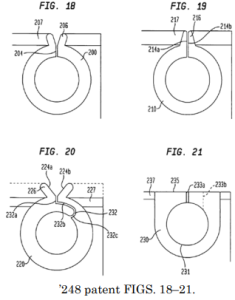

With the foundation of applying patent eligibility law to traditional software patents, we can more fully understand the Federal Circuit’s assessment of patent eligibility in an AI context in Recentive. This case concerned the eligibility of using machine learning, a subset of AI, to generate network maps and schedules for television broadcasts and live events. Recentive was appealing the district court’s ruling that its patents were directed to ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. §101. The Federal Circuit affirmed the lower court on the basis that the patents lacked an inventive concept and were directed to the abstract idea of using a generic machine learning technique in a particular environment.

Preparing network maps is a long-standing practice, if a sophisticated and niche one that has traditionally been performed by human beings. Recentive characterized its patents as applying existing, generic AI approaches to this specific context. In other words, “do it with AI.”

This type of “do it with AI” claim is ineligible under the two-step Alice inquiry. On the first step, the Court found that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of producing network maps and event schedules using known standard mathematical techniques. Recentive’s patent did not claim or describe how the machine learning technology resulted in a technological improvement. Instead, the patent was just about using AI to perform a task previously done by humans more quickly or efficiently without actually explaining how to accomplish that, which does not create eligibility. This is the same application of the Alice/Mayo test to traditional software patents.

On the second step, which looks at whether additional elements add an “inventive concept” that transforms an otherwise ineligible claim, the Court also found the patents failed. The patents only provided broad, functionally described common computing techniques and devices—again merely claiming an abstract idea.

While the Court framed Recentive as a question of first impression, the Federal Circuit has long held that software claims do not become eligible by limiting their application to a particular field or environment – eligibility does not result from taking an abstract idea and throwing in “do it on a computer” or “do it over the internet.” See, e.g., Intell. Ventures I LLC v. Capital One Bank (USA), 792 F.3d 1363, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2015). Similarly, that applying an existing technology to a new database does not create eligibility. See, e.g., SAP Am., Inc. v. InvestPic, LLC, 898 F.3d 1161, 1168 (Fed. Cir. 2018). Like the software patent cases that came before it, Recentive just applied AI to an existing framework.

While simply describing an abstract idea and adding “do it with AI” is not patentable (nor should it be), patent protection is available for all aspects of AI innovation. Practitioners have outlined best practices for drafting these patent applications, emphasizing the importance of providing sufficient detail and explaining the technical advantage of the claimed solution. https://www.fr.com/insights/thought-leadership/articles/ai-patent-eligibility-observations-and-lessons-for-the-us-and-china/ (“The key for applicants is to clearly show that their claim improves a technological process rather than merely uses technology to perform an existing process.”) https://www.troutman.com/insights/locke-lord-quickstudy-patenting-ai-inventions.html. (“Draft a strong patent application… Focus on technical aspects and algorithms… Provide experimental evidence and results…”). Of course, applicants must also ensure what is being claimed is commensurate with what was actually invented and not improperly tying up the basic tools of further scientific development. The USPTO’s most recent guidance on patent subject matter eligibility in 2024 provided some examples as well. See, e.g., https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2024-AI-SMEUpdateExamples47-49.pdf.

Recent district court decisions applying Recentive have also upheld claim eligibility for AI-related claims. Aon Re, Inc. v. Zesty.AI, Inc., No. CV 25-201, 2025 WL 1938214 (D. Del. July 15, 2025) (“The claim thus implements machine-learning technology in a specific way to address a practical technical problem: how to accurately and quickly assess the physical characteristics and condition of a property from an aerial image using machine learning models.”); Nielsen Co. (US), LLC v. Hyphametrics, Inc., No. CV 23-136-GBW, 2025 WL 1672002 (D. Del. June 13, 2025) (Claimed method provides “an improvement to the technical field of image processing, and, in particular, to improving speed and reliability of detecting overlays in images, with reduced or eliminated human oversight… These claims contain structure because they, inter alia, recite the specific [neural] networks used to perform the detection”).

Though all aspects of AI can be patented under Alice – and our patent eligibility law aims to ensure that AI patents do not over-claim in a way that would harm further AI innovation and usage – AI has nonetheless become yet another argument in support of patent eligibility reform. Various changes have been proposed over the past decade to expand the scope of section 101. Most recently, Senator Thom Tillis re-introduced the Patent Eligibility Restoration Act (PERA) in the Senate. https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/senate-bill/1546/text. This Act would eliminate all judicial exceptions to patent eligibility, replacing them with explicit and narrow statutory exclusions: 1) a mathematical formula not integrated into a claimed invention; 2) a mental process performed solely in the human mind; 3) an unmodified human gene as it exists in the human body; 4) an unmodified natural material as it exists in nature; and 5) a process that is primarily economic, financial, business, social, cultural, or artistic in nature. Most relevant to the issue of AI patenting, and what would be patent-eligible if PERA were to become law, the bill includes an eligibility escape hatch. It states that “the claimed invention shall not be excluded from eligibility for a patent if the invention cannot practically be performed without the use of a machine or manufacture.” This would mean that any abstract ideas could be patented if implemented on a computer leveraging computational capabilities. Effectively all AI inventions “cannot practically be performed without the use of a [computer].” This means that under PERA, “do it with AI” patents like the one found to be ineligible in Recentive would be eligible.

As a result, PERA would be a significant shift for patent eligibility of computer-related patents, and one that would harm rather than help the development and use of AI. Problematically, by untethering patent eligibility for abstract ideas from the requirement that patents be about technological improvements, PERA would allow patents that harm the development and widespread usage of actual technology. This in turn is likely to result in more patent thickets which will make AI development increasingly difficult and expensive, it will give incumbents more leverage over startups, and it risks holdups from foreign adversaries abusing the patent system. This is precisely the type of approach that allowed a flood of “do it on a computer” and “do it on the internet” patents to harm software development and usage for years. It is not a standard that is likely to help the United States remain the world’s leader in AI development. Nor is it a standard that will support innovators using AI as part of their development process.

And that is where our focus should lie: making sure our patent system is helping to incentivize AI technology development and usage in order to move the field forward. Patent eligibility has a pivotal gatekeeping role in the system, as the Federal Circuit correctly showed in Recentive. The line that has been drawn and applied in a software context for years is also the right one for AI.

The author represents that he is not being paid to take a position in this post. In addition to being an academic, the author is a practicing attorney and represents clients with interests on both sides of the post’s subject matter.