by Dennis Crouch

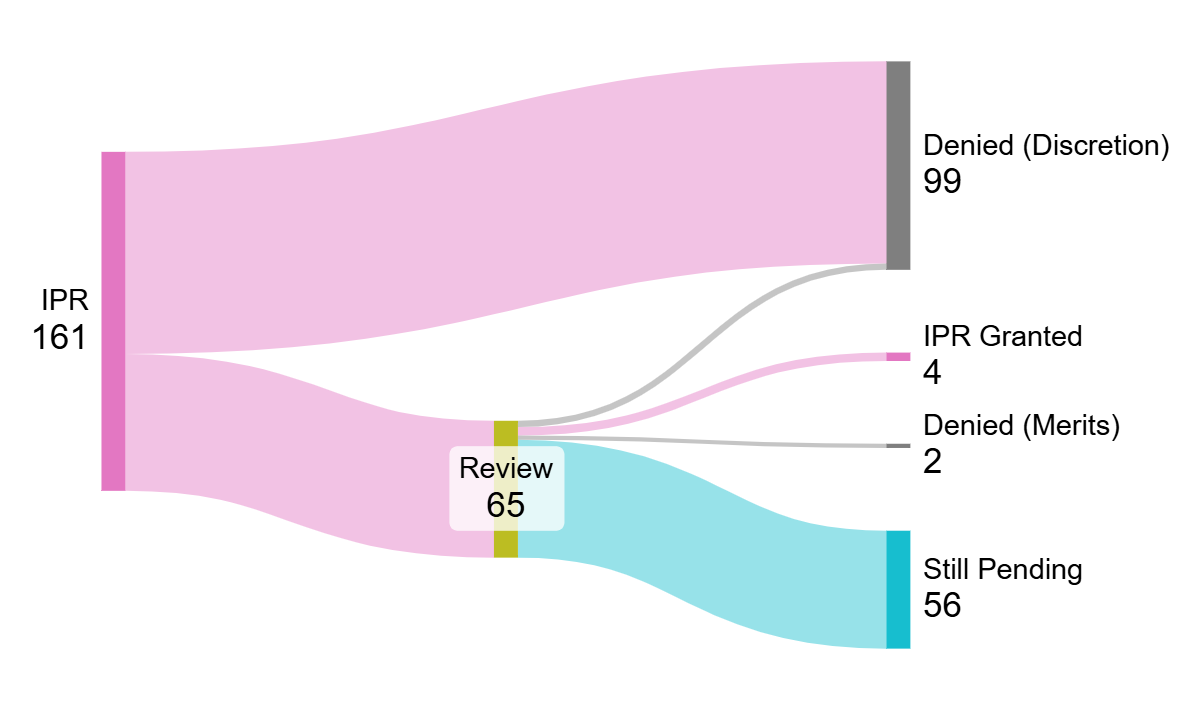

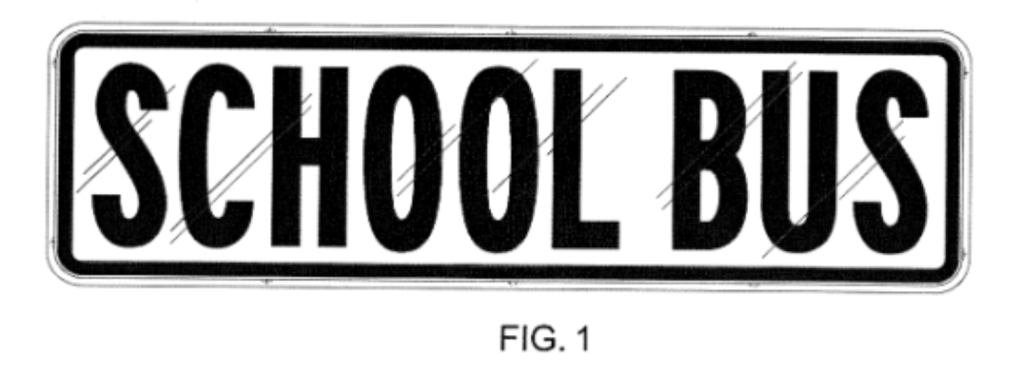

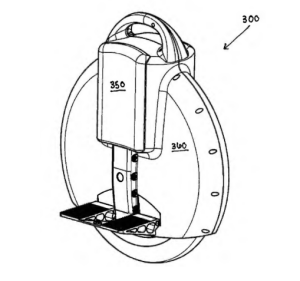

We have another mandamus petition at the Federal Circuit challenging the USPTO's IPR institution denials. In re Tesla, Inc., No. 26-116 (Fed. Cir. filed Dec. 2, 2025). The case involves patents asserted by Granite Vehicle Ventures LLC against Tesla's Self-Driving technology. But the petition's significance extends well beyond this particular dispute. Tesla advances a statutory interpretation argument that, if accepted, would fundamentally constrain the USPTO's claimed authority to deny IPR institution based on factors Congress never authorized.

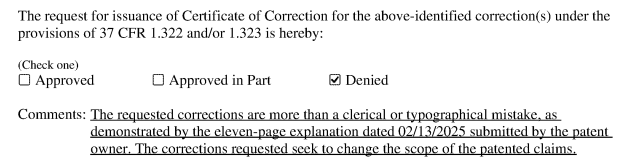

The core legal question is simple: Does 35 U.S.C. § 314(a) grant the Director unfettered discretion to invent new reasons to deny IPR institution? The USPTO has increasingly claimed discretionary power to justify denials based on a variety of novel explanations including "time-to-trial" concerns, "settled expectations," and other criteria that do not appear in AIA or its legislative history. In its petition, Tesla argues the USPTO's approach transforms a provision limiting the Director's authority into an unlimited grant of power to nullify IPR entirely.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.