Forest Labs v. IVAX (TEVA) and CIPLA (Fed. Cir. 2007).

Forest Labs v. IVAX (TEVA) and CIPLA (Fed. Cir. 2007).

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit today upheld Forest Labs patent on its billion dollar SSRI Lexapro (escitalopram oxalate) — rejecting IVAX’s arguments that the patent is anticipated and obvious. Based on two FDA extensions, the patent is set to expire on March 14, 2012.

This case is an important stepping stone in our new understanding of obviousness. Interestingly, in its multi-page discussion of obviousness, the appellate panel did not mention the Supreme Court’s recent landmark decision of KSR v. Teleflex.

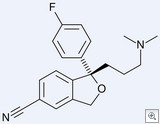

History: Forest holds an expired patent on a racemic form of citalopram. After considerable effort, Forest’s scientists doubled the strength of the drug by isolating the (+) stereoisomer (which turned out to be the only active isomer) and patented that isomer in a “substantially pure” form. A prior art pharmacologic paper had suggested that the (-) stereoisomer would be the potent isomer, but that reference did not describe the preparation of the enantiomer.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.