by Dennis Crouch

Miller Mendel, Inc. has petitioned the Supreme Court to review a Federal Circuit decision invalidating its background check software patent in a case that raises questions about both judicial independence and patent eligibility standards. The petition comes after both the district court and Federal Circuit found Miller Mendel's US Patent No. 10,043,188 ineligible under § 101 as directed to an abstract idea.

- Petition: PetitionforWrit

- Prior Post on the Case: Dennis Crouch, Alice Backs Anna: Federal Circuit Finds Miller Mendel’s Background Check Patent Abstract, Patently-O (July 18, 2024)

The Patent and Technology at Issue: The '188 patent covers a software system for managing pre-employment background investigations. The claimed system automates many aspects of the background check process, including collecting and storing applicant information, managing communications with references via email hyperlinks, and automatically generating suggested lists of law enforcement agencies based on an applicant's residential address. Miller Mendel accused the City of Anna police department (northern Texas) of infringement through its use of Guardian Alliance Technologies' background check platform. The City successfully moved for judgment on the pleadings arguing patent ineligibility under § 101. The court characterized the claimed automation features as merely implementing conventional background check steps on generic computer components.

Three Questions for Supreme Court Review

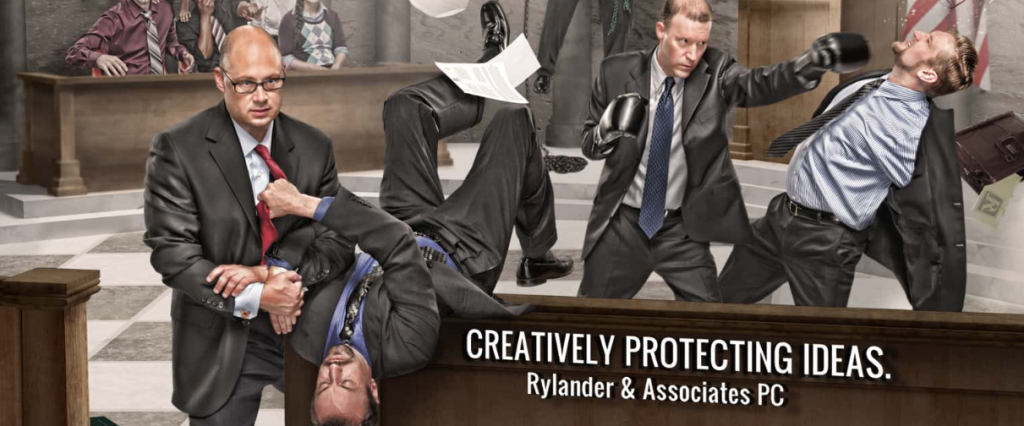

The petition, filed by Kurt Rylander of Rylander & Associates, presents three questions that go to fundamental issues in patent law and judicial administration:

1. Constitutionality of Removing Article III Judges

The most striking issue challenges the Federal Circuit's effective removal of Judge Pauline Newman from judicial duties for refusing to submit to mental health evaluations. The petition argues that the Federal Circuit's self-policing usurped Congress's exclusive constitutional authority to remove Article III judges through impeachment.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.