by Dennis Crouch

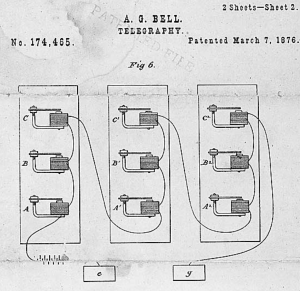

When Alexander Graham Bell filed his patent application on February 14, 1876, he titled it "Improvement in Telegraphy." Not "Telephone." Not "Apparatus for Transmitting Speech by Electricity." Just a modest tweak to the existing telegraph art. The United States government later alleged this was no accident. In United States v. American Bell Telephone Co., 128 U.S. 315 (1888), the government's bill of complaint charged that Bell "purposely framed his said application and claim in ambiguous and general terms" and "did not set forth or declare that his alleged invention had any relation to the art of transmitting articulate speech by means of electricity." The strategy worked, at least initially: the Patent Office examiner "did not understand the application to lay claim to the art of transmitting speech" and so "did not make an inquiry as to the state of that art or the patents or the printed publications concerning it." No search for the work of Reis, Meucci, or even the caveat filed that same day by Elisha Gray. Bell got his patent on March 7, 1876, three weeks after filing. The case raised serious fraud allegations that the Supreme Court addressed in a companion case, The Telephone Cases, 126 U.S. 1 (1888), but the patent survived.

Nearly 150 years later, patent attorneys are still doing the same thing, though the tools are better and the practice now has a name: targeted drafting. The basic idea is to frame an application so the USPTO routes it to a favorable art unit, where the examiner corps is more likely to allow claims. The mechanism is different from Bell's era, but the impulse is identical. A good negotiator picks a willing counterpart. A good patent prosecutor picks an art unit where the odds favor allowance. Analytics vendors have for years been marketing tools to predict art unit assignment and suggesting language changes to steer applications toward friendlier examiners.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.