Tag Archives: Affirmed Without Opinion

Federal Circuit Panel Splits on Standard of Review for Litigation Misconduct

Toshiba v. Imation: Claim Construction Three Ways

Mintz v. Dietz & Watson: Hindsight and Common Sense

Guest Post by Sarah Burstein: Apple v. Samsung

Guest post by Sarah Burstein, who will joining the faculty of University of Oklahoma College of Law this August. Her research focuses on design patents, an important piece in the smartphone wars. – Jason

Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2012) Download 12-1105

Panel: Bryson (author), O’Malley (concurring in part and dissenting in part), Prost

On May 14th, the Federal Circuit issued its first opinion in the world-wide, multi-front patent war between Apple and Samsung. In this opinion, the Federal Circuit considered the district court’s denial of Apple’s motion for a preliminary injunction based on infringement of three design patents and one utility patent, affirming in part and vacating in part. The opinion provides notable holdings in the areas of irreparable harm and nonobviousness.

In the motion, Apple argued that Samsung’s Galaxy S 4G and Infuse 4G smartphones infringed U.S. Des. Patent No. 618,677 (“the D’677 patent”) and U.S. Des. Patent No. 593,087 (“the D’087 patent”) and that Samsung’s Galaxy Tab 10.1 tablet computer infringed U.S. Des. Patent No. 504,889 (“the D’889 patent”). Apple also argued that all three of the devices—along with Samsung’s Droid Charge phones—infringed U.S. Patent No. 7,469,381 (“the ’381 patent”), which claims the iPad and iPhone “bounce” feature. The district court denied the motion based on, among other things, its findings that: (1) Samsung had raised substantial questions regarding the validity of the D’087 and D’889 patents; and (2) although the D’677 and ’381 patents were likely valid and infringed, Apple had failed to provide sufficient evidence on the issue of irreparable harm.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the denial of preliminary injunctive relief with respect to the D’677, D’087, and ’381 patents based on a lack of irreparable harm. The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court had not abused its discretion in finding no likelihood of irreparable harm with respect to the D’677 and ’381 patents. And although the Federal Circuit rejected the district court’s conclusion that the D’087 was likely anticipated, it still found no abuse of discretion in the denial of the preliminary injunction “[b]ecause the irreparable harm analysis is identical for both smartphone design patents.”

On the issue of irreparable harm, the Federal Circuit rejected Apple’s argument that the district court erred in requiring Apple to demonstrate a nexus between the claimed infringement and the alleged harm. According to the Federal Circuit: “If the patented feature does not drive the demand for the product, sales would be lost even if the offending feature were absent from the accused product. Thus, a likelihood of irreparable harm cannot be shown if sales would be lost regardless of the infringing conduct.” On appeal, Apple had argued that the district court had erred in rejecting Apple’s dilution theory of irreparable harm. The Federal Circuit disagreed, noting that “[t]he district court's opinion thus makes clear that it did not categorically reject Apple's ‘design erosion’ and ‘brand dilution’ theories, but instead rejected those theories for lack of evidence.” However, the Federal Circuit agreed with Apple that it “would have been improper” for the district court to completely reject “design dilution as a theory of irreparable harm.” The Federal Circuit did not explain why it “would have been improper” or provide any further explanation.

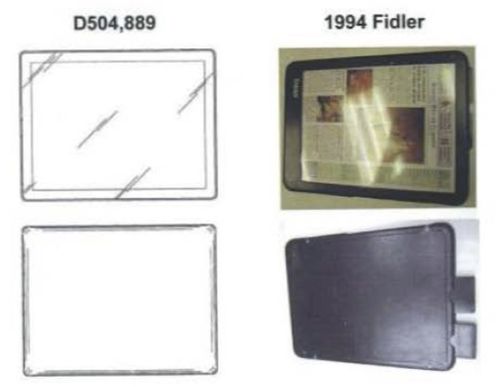

The Federal Circuit did, however, vacate the denial of preliminary injunctive relief with respect to the D’889 patent. The district court had found that the D’889 patent was likely obvious, using a 1994 tablet design (the “Fidler tablet”) as the primary reference. In the design patent context, any finding of obviousness must be supported by a primary reference—i.e., there must be “something in existence” that has “basically the same” appearance as the claimed design. If a primary reference is found, then the analysis proceeds. But if there is no primary reference, the inquiry ends—the design cannot be obvious. The Federal Circuit disagreed with the district court, holding that the Fidler tablet was not a proper primary reference. The Federal Circuit stated that “[a] side-by-side comparison of the two designs shows substantial differences in the overall visual appearance between the patented design and the Fidler reference,” pointing to the following illustration:

Without a primary reference, the district court’s finding that Apple was unlikely to succeed on the merits could not stand. And the district court had found that Apple had demonstrated a likelihood of irreparable injury with respect to the D’889 patent. However, because the district court had not made any findings on two of the preliminary injunction factors—the balance of harms and the public interest—the Federal Circuit remanded this portion of the case for further proceedings.

In her partial dissent, Judge O’Malley disagreed that the case should be remanded for further proceedings. According to Judge O’Malley, the district court’s discussion of these factors with respect to the other smartphone patents supported the entry of an injunction against the Galaxy Tab 10.1. Judge O’Malley also expressed concern that the remand would create undue delay, stating that “courts have an obligation to grant injunctive relief to protect against theft of property—including intellectual property—where the moving party has demonstrated that all of the predicates for that relief exist.”

Comment: The Federal Circuit’s conclusion regarding the Fidler tablet was surprising. Only a few years ago, a leading commentator observed that “[a]s a practical matter, [the requirement that the designs have ‘basically the same’ design characteristics] means that the primary . . . reference in a §103 design case needs to illustrate perhaps 75-80% of the patented design.” Perry J. Saidman, What Is the Point of the Point of Novelty Test for Design Patent Infringement?, 90 J. Pat. & Trademark Off. Soc’y 401, 419 (2008). Using that rule of thumb—or really, any ordinary meaning of the phrase “basically the same”—the Fidler tablet would easily qualify as a primary reference. Of course, that would not mean that the D’889 patent was obvious; indeed, there does not seem to be (at least from the public portion of the record) any persuasive evidence that an ordinary designer would have been motivated to modify the Fidler tablet in the manner shown in the D’889 patent. But this strict reading of the “basically the same” requirement may make it more difficult to prove obviousness in future design patent cases. And while it’s too early to declare a trend, it is worth noting that the Federal Circuit affirmed a rather strict reading of this requirement last year in Vanguard Identification Systems, Inc. v. Kappos (a case I discussed in a recent article).

The other especially striking portion of this opinion is the Federal Circuit’s unquestioning acceptance of Apple’s “design dilution” theory of irreparable harm. This sort of express equation of the harm caused by design patent infringement with the harm caused by trademark dilution is unprecedented in design patent case law (although not in the academic literature) and Apple’s theory deserves more attention and consideration than the Federal Circuit appears to have given it in this case.