Tag Archives: Affirmed Without Opinion

Federal Circuit Unanimously Affirms Inequitable Conduct, Teaching that Curing False Statements Needs to be Done Clearly

Fascinating Split Decision on Impact of a Rule 36 Affirmance that May have Significant Consequences

Judge Rader’s Obviousness Tutorial: Including the Conclusion that Older Prior Art is Less Credible and a Restatement that Objective Indicia of Nonobviousness Play a Critical Role

SkinMedica v. Histogen

Federal Circuit Rejects Supreme Court Original and Exclusive Jurisdiction over State-vs-State Inventorship Disputes

Working out the Kinks in Post-Issuance Reviews: Versata v. SAP

Federal Circuit gets Technical with PTAB Failures

Federal Circuit Begins its Campaign for Patent Clarity

Guest Post: Monopoly Without Apology

Supreme Court: Patent Rights Block Farmers from Saving and Re-Planting Patented Seeds

Double Patenting Problems when Inventors Move to a New Employer

In re Owens (Guest Post by Prof. Sarah Burstein)

Guest post by Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law. Professor Burstein will be speaking at Stanford's conference on Design Patents in the Modern World next week. – Jason

In re Owens (Fed. Cir. Mar. 26, 2013) Download 12-1261

Panel: Prost (author), Moore, Wallach

Earlier this week, the Federal Circuit issued its opinion in In re Owens. (For prior Patently-O coverage of this case, see here.)

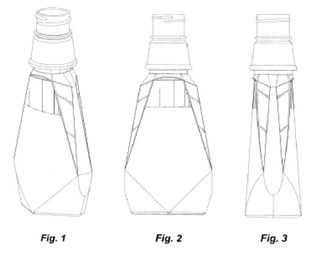

In this case, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTO’s rejection of U.S. Design Patent Application No. 29/253,172. The ’172 application claimed the following design:

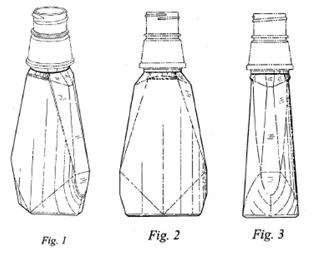

The ’172 application was a continuation of—and claimed priority based on—U.S. Design Patent Application No. 29/219,709 (which issued as U.S. Des. Patent No. 531,515). The ’709 application claimed the following design:

In design patents, broken lines can be used to show: (1) unclaimed “environmental” matter (often, though not always, shown with dotted lines); or (2) unclaimed boundaries (often shown using dot-dashed lines). According to the MPEP, an “[a]pplicant may choose to define the bounds of a claimed design with broken lines when the boundary does not exist in reality in the article embodying the design. It would be understood that the claimed design extends to the boundary but does not include the boundary.”

So, essentially, the ’172 application broadened the original claim by changing a number of solid lines to dotted lines. Importantly, though, this was not the problem in Owens. (Indeed, the Federal Circuit went so far as to say in dicta that these types of dotted disclaimer lines “do not implicate § 120.” Whether that blanket statement really fits with the logic of the rest of the opinion is an issue for another day.)

The problem was the addition of the dot-dashed boundary line on the front panel. The examiner found no evidence that Owens possessed that “trapezoidal region” (as the Federal Circuit called it) at the time of the original application. Therefore, the application was rejected for failure to comply with 35 U.S.C. § 112, ¶ 1 and as “obvious in view of the earlier-sold bottles.” The Board affirmed.

On appeal, Owens argued, among other things, that the continuation application did not add new matter because all of the portions of the claimed partial design (including the trapezoidal area on the front panel) were “clearly visible” in the parent application. In support of this argument, Owens relied on In re Daniels.

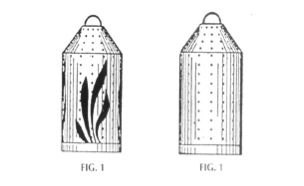

In Daniels, the Federal Circuit held that a continuation application that claimed the design shown below on the right was entitled to the priority date of its parent application, which claimed the design shown below on the left:

But the Federal Circuit distinguished Daniels, stating that:

The patentee in Daniels did not introduce any new unclaimed lines, he removed an entire design element. It does not follow from Daniels that an applicant, having been granted a claim to a particular design element, may proceed to subdivide that element in subsequent continuations however he pleases.

According to the court, “the question for written description purposes [in this case] is whether a skilled artisan would recognize upon reading the parent’s disclosure that the trapezoidal top portion of the front panel might be claimed separately from the remainder of that area.” The Federal Circuit concluded that the Board’s finding on that factual issue was “supported by substantial evidence because the parent disclosure does not distinguish the now-claimed top trapezoidal portion of the panel from the rest of the pentagon in any way.”

The court did not stop there, though. It went on to answer “a question raised implicitly in Owens’s appeal and explicitly in amicus briefing—whether, and under what circumstances, Owens could introduce an unclaimed boundary line on his center-front panel” without running afoul of the written description requirement. Section § 1503.02 of the MPEP currently provides that:

Where no boundary line is shown in a design application as originally filed, but it is clear from the design specification that the boundary of the claimed design is a straight broken line connecting the ends of existing full lines defining the claimed design, applicant may amend the drawing(s) to add a straight broken line connecting the ends of existing full lines defining the claimed subject matter. Any broken line boundary other than a straight broken line may constitute new matter . . . .

The Federal Circuit rejected this rule, noting that if Owens had simply placed the boundary line at the widest point of the front panel, “the resulting claim would suffer from the same written description problems as the ’172 application.”

So what are applicants supposed to do going forward? According to the Federal Circuit, “the best advice for future applicants was presented in the PTO’s brief, which argued that unclaimed boundary lines typically should satisfy the written description requirement only if they make explicit a boundary that already exists, but was unclaimed, in the original disclosure.”

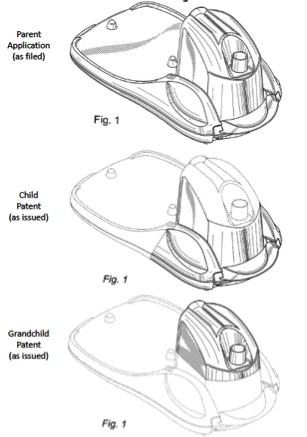

Notably, this rule is—as the PTO admitted at oral argument—a break from (at least some) past PTO practice. For example, as Method Products, Inc. pointed out in its amicus brief, the PTO allowed all of the following claims for a humidifier design:

If nothing else, this case makes it clear that the PTO needs to provide greater guidance on the written description requirement and, in particular, on the use of unclaimed boundary lines. Hopefully, the PTO will do so soon.