Guest post by Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law. Professor Burstein will be speaking at Stanford's conference on Design Patents in the Modern World next week. – Jason

In re Owens (Fed. Cir. Mar. 26, 2013) Download 12-1261

Panel: Prost (author), Moore, Wallach

Earlier this week, the Federal Circuit issued its opinion in In re Owens. (For prior Patently-O coverage of this case, see here.)

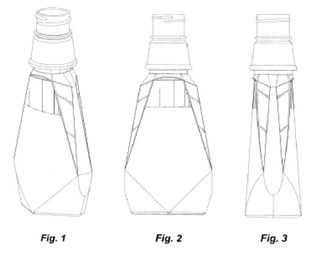

In this case, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTO’s rejection of U.S. Design Patent Application No. 29/253,172. The ’172 application claimed the following design:

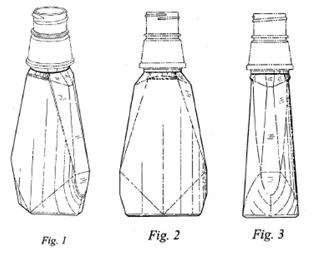

The ’172 application was a continuation of—and claimed priority based on—U.S. Design Patent Application No. 29/219,709 (which issued as U.S. Des. Patent No. 531,515). The ’709 application claimed the following design:

In design patents, broken lines can be used to show: (1) unclaimed “environmental” matter (often, though not always, shown with dotted lines); or (2) unclaimed boundaries (often shown using dot-dashed lines). According to the MPEP, an “[a]pplicant may choose to define the bounds of a claimed design with broken lines when the boundary does not exist in reality in the article embodying the design. It would be understood that the claimed design extends to the boundary but does not include the boundary.”

So, essentially, the ’172 application broadened the original claim by changing a number of solid lines to dotted lines. Importantly, though, this was not the problem in Owens. (Indeed, the Federal Circuit went so far as to say in dicta that these types of dotted disclaimer lines “do not implicate § 120.” Whether that blanket statement really fits with the logic of the rest of the opinion is an issue for another day.)

The problem was the addition of the dot-dashed boundary line on the front panel. The examiner found no evidence that Owens possessed that “trapezoidal region” (as the Federal Circuit called it) at the time of the original application. Therefore, the application was rejected for failure to comply with 35 U.S.C. § 112, ¶ 1 and as “obvious in view of the earlier-sold bottles.” The Board affirmed.

On appeal, Owens argued, among other things, that the continuation application did not add new matter because all of the portions of the claimed partial design (including the trapezoidal area on the front panel) were “clearly visible” in the parent application. In support of this argument, Owens relied on In re Daniels.

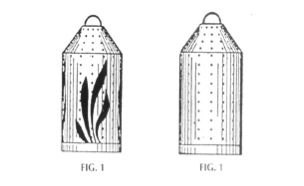

In Daniels, the Federal Circuit held that a continuation application that claimed the design shown below on the right was entitled to the priority date of its parent application, which claimed the design shown below on the left:

But the Federal Circuit distinguished Daniels, stating that:

The patentee in Daniels did not introduce any new unclaimed lines, he removed an entire design element. It does not follow from Daniels that an applicant, having been granted a claim to a particular design element, may proceed to subdivide that element in subsequent continuations however he pleases.

According to the court, “the question for written description purposes [in this case] is whether a skilled artisan would recognize upon reading the parent’s disclosure that the trapezoidal top portion of the front panel might be claimed separately from the remainder of that area.” The Federal Circuit concluded that the Board’s finding on that factual issue was “supported by substantial evidence because the parent disclosure does not distinguish the now-claimed top trapezoidal portion of the panel from the rest of the pentagon in any way.”

The court did not stop there, though. It went on to answer “a question raised implicitly in Owens’s appeal and explicitly in amicus briefing—whether, and under what circumstances, Owens could introduce an unclaimed boundary line on his center-front panel” without running afoul of the written description requirement. Section § 1503.02 of the MPEP currently provides that:

Where no boundary line is shown in a design application as originally filed, but it is clear from the design specification that the boundary of the claimed design is a straight broken line connecting the ends of existing full lines defining the claimed design, applicant may amend the drawing(s) to add a straight broken line connecting the ends of existing full lines defining the claimed subject matter. Any broken line boundary other than a straight broken line may constitute new matter . . . .

The Federal Circuit rejected this rule, noting that if Owens had simply placed the boundary line at the widest point of the front panel, “the resulting claim would suffer from the same written description problems as the ’172 application.”

So what are applicants supposed to do going forward? According to the Federal Circuit, “the best advice for future applicants was presented in the PTO’s brief, which argued that unclaimed boundary lines typically should satisfy the written description requirement only if they make explicit a boundary that already exists, but was unclaimed, in the original disclosure.”

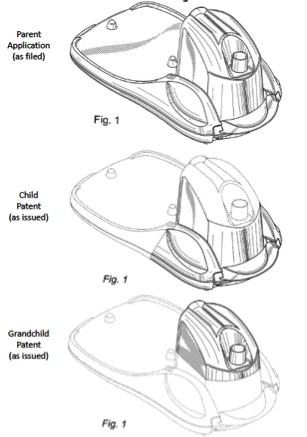

Notably, this rule is—as the PTO admitted at oral argument—a break from (at least some) past PTO practice. For example, as Method Products, Inc. pointed out in its amicus brief, the PTO allowed all of the following claims for a humidifier design:

If nothing else, this case makes it clear that the PTO needs to provide greater guidance on the written description requirement and, in particular, on the use of unclaimed boundary lines. Hopefully, the PTO will do so soon.

OK, then!

“As the battle between you two rages, the pendulum has swung back in Mooney’s favor.”

LOL – your subjective viewpoint is as compelling as Mr. Blue Sky Is Falling’s APPEAL EVERYTHING (TM) responses.

My points are valid.

My points remain valid.

Whether or not you agree is rather immaterial. My being a “dickhead” to you matters not at all.

But thanks for your opinion. It means nothing (in the overall objective scheme of things). Truth cares not for popularity contests.

Seriously, anon?

As the battle between you two rages, the pendulum has swung back in Mooney’s favor.

You have been losing for some time, and your recent indiscriminate use of firepower and resources was like your own Battle of the Bulge. You seemed to have “caught Mooney by surprise with this offensive. This was achieved by a combination of Mooney overconfidence, preoccupation with his own offensive plans, and poor reconnaissance” (Wikipedia).

After a period when a critical part of MM’s offensive capability was unavailable, you encountered fierce resistance and blocked access to arguments you counted on for success, and you were thrown behind schedule. Improving conditions allowed MM to muster intellectual reinforcements, “sealing the failure of your offensive”.

You seem to have now retreated to the defensive position of your own Siegfried Line.

In other words, it is you that is attempting to be too clever by half. Pointing this out is only “being a dickhead” because I am ruining your conflation party.

Too bad.

“Anon, you’re not being clever, you’re just being a dickhead.”

Actually – neither.

I am making this very straightforward and hosing down the dust being kicked up. You are conflating two very different concepts – needlessly so.

Sorry you don’t like it, but that is no indication that I am being a dickhead.

Anon, you’re not being clever, you’re just being a dickhead. Your posts leave much to be desired–for instance, “actual boundary” can be OF environment. Yes, the depicted environment does have actual boundaries.

If you want to succinctly and directly answer my question of 2:38 pm, or any others, feel free.

***********************************

There is no question in my mind that a dashed-dot line represents an environmental boundary, just as could a dashed or a dotted line; the only difference between dashed-dot and dashed or dotted is that the dashed-dot environmental boundary is used to suggest that the boundary of the claimed design immediately abuts the dashed-dot line at all points, whereas there is no suggested made where simple dashed or dotted environmental boundary lines are used.

Again, if the inferred design boundary to be “distinctly” described in any such situation, a rule to that effect would need to be in place, which it is not. I would ask what the merit would be of using a dashed-dot line in that situation, versus a solid line depicting design boundary instead.

The only reason I can see is an unsuccessful attempt to include in the claim in the child that which was not described in the parent, by not explicitly describing in the child that which was not described in the parent.

Nice try. Whether explicitly or impliedly included in the claim of the child, the boundaries of the design ARE described therein, and are required to have been previously disclosed in the parent.

The focus in these proceedings, at least from the appellant’s perspective, always seemed to be “Yes, but the dashed-dot line is UNCLAIMED.” This attempt to focus on what was unclaimed was a red herring–what was important was NOT that which WASN’T CLAIMED, it was that which WAS CLAIMED. The utility of a dashed-dot line was limited to identifying the boundaries of the claimed design, and it was the boundaries of the CLAIMED DESIGN that were of interest, and which required support in the parent.

Remember, boundaries of the design describe (in part) the claimed SM. In this case there was no description in the parent of a boundary at a location immediately abutting at all points the dashed-dot line depicted in the child.

Not being coy at all, IBP.

My answer at 1:31 is forthright. Actual boundary and environment are two distinct concepts.

OK, I take it you’re being coy about my wording, and that you believe that although the boundary of the claimed design, if in fact described where a dashed-dot line was used, WOULD HAVE TO BE inferred–but that it is in fact not described and therefore not inferred.

If that’s not it, then you have lost me.

If it is, then I don’t understand why you’re being coy on a point on which we seem to agree.

That is funny.

However, my 1:31 PM post explicitly answered the question (you may have additional questions, but your follow-on post of 2:37 misses the answer provided.

anon–

Your 1:30 post did not provide an answer to that question, unless you want me to infer that you believe dashed-dot lines to be environmental.

Funny you brought up drafting. When I did my eng, we still drafted manually, the first CAD was just coming on line and we had a whole room of huge IBM mainframes to run it!

But the funny part was the name of my first manual drafting teacher:

“Mr. Edge”

Seriously.

Question in reply to your question:

Why did you ignore the answer provided at 1:31 PM?

anon–

simpler question: what do you believe a dashed-dot line to mean?

anon–

If dashed-dot lines are permitted and remain “unclaimed”, then:

1) where is the boundary of the claimed design?

2) how do you know where (1) is?

3) what exactly does any dashed-dot line make “explicit?

4) how can a boundary “exist” [be described] in the original disclosure without having been claimed?

My answers:

1) infinitely close to the dashed-dot line at all points on that line

2) you infer its location from the combination of the known location of the dashed-dot line, and the infinite closeness of the boundary of the claimed design to that dashed-dot line

3) the boundary of the unclaimed environment

4) via a dotted line, a dashed line, or a dashed-dotted line, all of which describe environment

Dashed-dotted lines are an absurdity, unless you wish to argue that inferring the boundaries of the claimed design satisfies 112. For any such inference to be reasonable, there must be an acceptable convention somewhere in the regs that defines the boundary of a claimed design as being infinitely close to, but not coextensive with, a dashed-dotted line in a drawing.

There is no such reg.

Even if there were, a boundary in a child would still not be made “explicit” by inclusion of a dashed-dotted line, it would be made “implicit”.

For my money, Mooney is right–there has to have been a solid line in the parent in order for there to be a solid line in the child, or if you buy the inferential argument, a dashed-dotted line in the child–but in such case, why not just use a solid line?

I know the examples the PTO presented in its seminar. I suggest you look them up, then we can continue this discussion.

Consider this question, though: what if in the parent drawing the two lower lines of the polygon did not meet at a point but were instead connected by another line, and the appellant had put a dashed-dot line somewhat higher than the original solid connecting line but parallel to it, yet still below the level of the 2 side intersections?

In other words, what if the parent had disclosed a hexagon instead of a pentagon, and that pentagon shape had been maintained in the child via a dashed-dot line? Would that ornamental appearance have been disclosed in the parent?

Actual boundary is determined by solid lines.

Period.

The environment lines are just that: environment lines (think of it as a different function than determining boundary). Do you have a drafting background? This is not a difficult ‘art’ to come up to speed on (but you will need to do more than Malcolm and his ‘sniff’ learning protocol).

“(or blogtrolls like “anon”) are scurrying about spewing bile on anyone who would dare question their authority but otherwise contributing zilch”

LOL – more misrepresentation Malcolm – your contributions were zilch and my pointing out that you didn’t understand the basics was directly on point. That must be a wonderful imaginary world you live in. You clearly have no actual engineering design background (probably wasn’t a requirement for your wasted PhD, was it?).

Try actually reading what I wrote this time around.

Anon–

What do you believe it to mean? If neither explicitly nor by inference, then exactly how is the boundary of the claimed design determined?

Gandy was a piece of…work.

italics off

I’m certainly interested, IBP. But as I’ve noted repeatedly, design patent law is a cesspool that needs to be re-written from the ground up. Discussing how to “resolve” the conflicting judicial decisions and the gaping logical holes in the current scheme is not very fun, particularly when ridiculously self-important stuffed shirts like “Jim Gandy” (or blogtrolls like “anon”) are scurrying about spewing bile on anyone who would dare question their authority but otherwise contributing zilch.

But you did identify something in the decision which I commented on earlier:

And did the court quote the PTO’s brief fairly? How could “a boundary” “in the initial disclosure” “exist” but be “unclaimed”? (BTW, boundaries are not “claimed”, they help “describe” what IS claimed–an ornamental appearance). I can think of only one way: by being environmental boundaries illustrated in the original disclosure using dotted or dashed lines, or dashed-dot lines.

Right. In other words, if you want your drawing (i.e., the claim) in your continuation application to include a particular dashed or dotted line, that line needs to appear in the original disclosure. Shockingly reasonable.

“Maybe I should guerrilla the conference dressed entirely in contrefacon.”

Not sure how many made it through the comment to this point.

“meaning that the actual boundary of the claimed design is determined by inference.”

That’s not what it means.

Wow, nobody seems to care about design patents.

I find that odd.

Here we have a potentially engaging issue, one with a somewhat interesting subtlety: the fact that an “unclaimed dashed-dot boundary line” describes the boundary NOT of the claimed design, but of the environment surrounding that design, meaning that the actual boundary of the claimed design is determined by inference.

Thus raising the question whether this particular type of description by inference satisfies 112.

I find this to be a fun question. Consider that in some situations, the entire periphery of a design could, if this were acceptable, be described by inference, without use of a single solid line. Does an unclaimed dashed-dot line describing the boundary of unclaimed environment surrounding the design necessarily imply the boundaries of the claimed design itself, and is that characterization sufficient to satisfy 112?

And did the court quote the PTO’s brief fairly? How could “a boundary” “in the initial disclosure” “exist” but be “unclaimed”? (BTW, boundaries are not “claimed”, they help “describe” what IS claimed–an ornamental appearance). I can think of only one way: by being environmental boundaries illustrated in the original disclosure using dotted or dashed lines, or dashed-dot lines.

Is this what the PTO’s brief said? Is it considered possible to later claim previously disclosed but unclaimed environmental boundaries?

Of course I have my own answers to these questions, but it surprises me that nobody seems to care about such issues. You know, design is a big deal in Europe. It means big money, big challenges, and big billings. ROW, including USA, has not arrived at the same point, but it is creeping in that direction. VERY slowly.

I forget the constitution of the invitees to the upcoming “design patent conference”, but I remember thinking that there is nobody there, with the possible exception of one or two people, who has anything really meaningful to bring to the table. The rest of it is like an awareness exercise–a day late, and a dollar short. This is a big issue elsewhere in the world, and a lot of work has been done and consideration given. Hopefully those 2 panelists in the know will do what they can to enlighten the remainder.

But the apparent lack of interest is still surprising to me. Way back when I wrote the patent exam and took patent bar courses, I don’t think design patents were addressed, at all. Even when I was applying to write the exam, I wondered how well the required technical qualifications to be a patent attorney or agent would serve those clients wishing to secure design patent protection. The answer? Not at all. Legal background certainly helps, but not any of the required technical backgrounds, so it seems marginalized even by the PTO. “Oh well, since there’s really nothing to do, anybody qualifed to do utility patents will be able to do design patents.”

Either we should get serious about the system of examination, or we should go to a registration system. The mish-mash of protections afforded by patent, copyright, etc. doesn’t work at all well. It’s bizarre, inconsistent, incomplete, and inefficient.

Of course movements in various directions have been afoot for a while, but nothing significant has really happened in my opinion. This upcoming conference is likely to be just another link in the chain of insignificant events. I notice, for instance, that it is limited to the consideration of “design patents”, without any mention of any broader context.

As far as focusing on design patent law, if the article above is any indication of the depth of consideration design patent law receives, then there won’t be any valuable interpretation, analysis, or opinion presented, just case reports. The only really original expression by the author is in the last paragraph, and it is of little, if any, value. “If nothing else”?! This case makes it clear that there are significant issues that need to be discussed and resolved, with no such discussion presented by the author. We KNOW what the opinion says and how the decision went–it is just as fast, and more worthwhile, to read the opinion as it is to read the summary article, IMO. The article above was yet another summary of information already available, and didn’t even identify, let alone address, the important questions raised.

I will stop, finally, because I realize that nobody on this board seems to be very interested in these issues. Maybe I should guerrilla the conference dressed entirely in contrefacon.

Mooney–

Surface ornamentation, independent of the article to which it is applied, whether or not it “can” or more properly “could” be applied to multiple different types of articles, is of course not patentable, as ineligible SM.

In the textual claim, the underlying article of manufacture must be described–and since the WD must describe how to make and use, how the ornamentation or configuration affects the appearance of the article must be described. Obviously, issues such as the scale at which surface ornamentation is applied, or the scale at which surface texture or configuration is applied, can result in markedly different ornamental appearances of an article of manufacture.

So HOW it IS applied to something, not just whether or not it COULD be applied, is critical to satisfying 112, IMO. That is why “Alternate positions of a design component, illustrated by full and broken lines in the same view are not permitted in a design drawing.” (37 CFR 1.152)

As far as putting descriptive text in the app is concerned, applicants’ hands are tied.

Once again, I don’t claim to be any sort of “design patent expert”.

I’d love to hear from someone who believes they are.

Well done, IBP. As the saying goes, I’d like to subscribe to your newsletter.

One question/comment re this:

environmental information is needed to the extent that how to make and use the invention must be taught.

If the ornamental design is such that it could be applied to any surface (or, if I may be so bold, displayed on any screen), then it should not be necessary to include any environmental information in the drawing. In other words, wouldn’t it suffice to simply include text in the application to the extent that the design can be applied to the surface of any object (or displayed on any screen)? An ornamental design “for a shoe” (e.g., a drawing of a flower with nineteen petals around a square eye) that does not claim any part of the shoe can’t possibly be patentable over an indentical design “for a lampshade” that does not claim any part of the lampshade.

Design patents protect an ornamental appearance, which is legally considered to be the totality of a disclosure (that is, the overall appearance of the design)–hence the singular substantial similarity-based “ordinary observer” test, and the rejection of the potentially multiple “point(s) of novelty” test of infringement.

The singular nature of the totality of the disclosure is also the reason for the single permitted claim–the applicant claims a singular ornamental appearance.

Because only a single claim is permitted, it is improper to extend that claim to cover more than a single ornamental appearance. Since subcombinations have distinct ornamental appearances from both each other and from the larger combination, they cannot logically be included within the single claimed ornamental appearance. Therefore, if drawings that describe more than one single ornamental appearance are presented in the original app, the PTO will issue a restriction requirement, requiring the applicant to elect a single disclosed ornamental appearance for continued prosecution.

Notice that this restriction requirement will be applied to applications in which different drawing figures independently show more than one distinct ornamental appearance, NOT to the situation where, for instance, there is only a single drawing, which would result in a new distinct ornamental appearance if some parts of it were removed–for instance, Daniels.

Why was a restriction requirement not appropriate in Daniels? Because there was not more than one ornamental appearance independently, or distinctly, depicted in the drawings and therefore claimed in the claim.

The point of a design application is to evidence possession of an ornamental appearance, which if anything less than the totality of the drawing disclosure, must of course be able to be extracted from the drawings without adding new matter.

Appellant tried to side-step this requirement by using the logically-insufficient argument that the dashed-dot line was “unclaimed” in the child application. Rubbish. There is zero support in the parent drawings for the resulting ornamental appearance depicted in the child. The “unclaimed” dashed-dot line is a red-herring–everything is claimed up to the line, but not including the line?

I’ve never heard anything so ridiculous. Since an invention must be distinctly claimed, the metes and bounds must be known. Where are the metes and bounds regarding the dashed-dot line? Is there some sort of limit situation, where infinitely close to the line is claimed, but not the line itself? OK, then to actually describe the ornamental appearance claimed, replace the dashed-dot line with a solid line infinitely close to the location of the dashed-dot line, and what do you have? You have a visual appearance that was not depicted in the parent.

Whether or not any or all portions of any “design element” are visible in the parent is utterly irrelevant, because it is the actual selection of any or all of those portions that defines and discloses the resulting overall ornamental appearance claimed. Actual selection means that an ornamental appearance that was actually disclosed in the parent must result.

The panel said that “It does not follow from Daniels that an applicant, having been granted a claim to a particular design element, may proceed to subdivide that element in subsequent continuations however he pleases.”

Yes, but WHY NOT?

First, the applicant is NOT granted a claim to any “particular design element”, it is granted a claim to the single ornamental appearance that is depicted. The above quote should have had “ornamental appearance” in place of “design element” and “element”.

The answer to the question “WHY NOT?” is then apparent–because he could only claim subdivisions if they were of independently disclosed ornamental appearances of which he evidenced possession in the drawings, which if anything less than the totality of the drawing disclosure, must of course be able to be extracted from the drawings without adding new matter. That is the essential restriction on an applicant doing “whatever he pleases”. That is how “the original disclosure ‘clearly allows PHOSITAS to recognize that the inventor invented what is claimed'”.

“In our view, the best advice for future applicants was presented in the PTO’s brief, which argued that unclaimed boundary lines typically should satisfy the written description requirement only if they make explicit a boundary that already exists, but was unclaimed in the original disclosure. Although counsel for the PTO conceded at oral argument that he could not reconcile all past

allowances under this standard, he maintained that all

future applications will be evaluated according to it.”

I don’t think this is good advice at all. First, it is not elements or boundaries that are claimed in a parent, it is a single, unitary ornamental appearance–hence the single, unitary “substantial similarity” test for infringement and the rejection of the mosaiced “points of novelty” test. ALL “boundaries” depicted in the parent contribute to the claimed overall ornamental appearance.

Second, so-called “unclaimed boundary lines” should be rejected in their entirety. The term is a non-sequitur: “unclaimed boundary”. Ridiculous. Boundaries are something applicants MUST claim in order to define the ornamental appearance they claim.

The drawings DO NOT define what an invention IS NOT, they define what an invention IS. They are depicting THE INVENTION. Dashed or dotted lines are considered “environmental” and potentially necessary because the textual claim must be to the ornamental appearance of an ARTICLE OF MANUFACTURE, and so environmental information is needed to the extent that how to make and use the invention must be taught. They may exist IN ADDITION TO solid lines, but not IN LIEU OF solid lines, which is what this absurd “dashed-dot” line purports to do.

Again, it is just as easy to draw a solid line, infinitely close to the “dashed-dot” line, that entirely solves the issue. If there was a solid line at that same location in the parent, there was disclosure of the location of that line in the child, and you’re good. If not, an applicant cannot attempt to define the invention by what it “IS NOT”, as any such attempt would not satisfy the requirements of 112.

Mooney–

It is amazing that the appellant moved ahead with this appeal.

“OK, what have we got?”

–“Well, we have some old non-binding PTO guidance that even the PTO doesn’t agree with anymore, that some of us have been following for a while, and some old granted patents that are also non-binding.”

“Hmmm, I seem to remember seeing a ‘design patent’ headline in the Times last weekend…OK, let’s run with it!”

–“(Yes…!)”

What are all those applicants and patentees who mistakenly relied on the “guidance” doing today?

Mooney–

In my opinion, the PTO’s relevant prior representations were in this case really egregious examples of a lack of understanding or consideration of the law, something even the PTO came to understand.

Prosecution of this appeal was a total waste of time, arguing that an older, non-binding PTO interpretation that even the PTO disagreed with should now be binding on the PTO, to satisfy the “settled expectations” of the “design patent community”. Indeed, PTO disagreement was the very reason for the appeal, and for the life of me I can’t see any reasonable expectation that the decision would have gone the other way, which would be forcing the PTO to adopt an interpretation that even IT admitted was a mistake.

Because I have prosecuted design patent applications, I consider myself part of the “design patent community”–one who was aware of that PTO guidance, investigated that guidance, rejected it as unlawful, and never relied upon it. IMO this unlawful PTO guidance cannot be said to have reasonably created “settled expectations” in the “design patent community”, something with which the CAFC panel agreed.

Mooney, remember “examiner Gandy” from the other thread? When I said there that design patent law was only the second most important issue raised in that thread, his attitude of supremacy was the most important issue. He absolutely could not understand how any interpretation other than his own could make sense, or be lawful.

I couldn’t even bring myself to respond in a way that wouldn’t get my post deleted by the moderators, I was beside myself with rage. I wonder how Gandy is feeling today.

Jason: So, essentially, the ’172 application broadened the original claim by changing a number of solid lines to dotted lines. Importantly, though, this was not the problem in Owens. (Indeed, the Federal Circuit went so far as to say in dicta that these types of dotted disclaimer lines “do not implicate § 120.”

They certainly do implicate § 120 if the initial disclosure included solid lines where the “disclaimer lines” are later claimed, without any suggestion that the applicant was in fact intending to disclose a broader design in that original disclosure. How can that not be the case?

The Daniels decision, by the way, is also a pile of incomprehensible g-rbage. So applicants can broaden their design claims by removing limitations when those elements are deemed to be “entire design elements” by the Federal Circuit? When, pray tell, does an element in a design become an “entire design element”? There’s no shortage of cream pies at the design patent clownshow.

At first glance, congratulations are due to the CAFC panel for this decision. Absolutely. Bravo!! Hopefully, the opinion represents a triumph of rational logic.

Agreed on that. Hopefully much more “rational logic” will be applied to disinfect the cesspool of design patent “law”.

I called this outcome on the previous Owens thread.

The patentee and its counsel Saidman relied on PTO representations made in both the MPEP and in a public seminar, which representations were rubbish.

Now, in fairness to both the patentee and Saidman, reliance on PTO representations that do not carry the force of law are not per se unreasonable, but the logic underlying those representations does have to be investigated. When this rule was seriously examined by myself and others, it was found to be logically unsupportable.

The patentee’s argument was completely sunk when the PTO admitted that those issuances supporting the patentee’s argument were wrongly decided by the PTO.

I didn’t have the time to make a big post earlier, but I did write up something, that I might post in this thread now that this is done, because the matching opinion now means that I don’t have to buff up the writing at all–but it seems superfluous now, as the case is decided, with the most sensible outcome possible (although I haven’t yet combed through the opinion).

At first glance, congratulations are due to the CAFC panel for this decision. Absolutely. Bravo!! Hopefully, the opinion represents a triumph of rational logic.

Thanks, fixed.

BTW, this case relates to the bottle design for P&G’s Crest Pro-Health Care line of mouthwashes/rinses.

Dennis,

There are a couple of errors in this posting. The author of tihs opinion is Prost (not Newman). Also the date of the decision issuing is March 26, 2013 (not March 26, 2012).