May 2018

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

Copyrighting Software: Case Likely Heading to Supreme Court

Petition: Is the government a person and can it infringe?

Design Patents vs Utility Patents

Is Ineligibility a Statutory Defense to Patent Infringement

Sorting Cases: Applying Collateral Estoppel Mid-Stream

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

Hyatt v. USPTO: Mandamus Action Requesting an Impartial Administrative Review

Layers of Doctrine with a Faulty Claim Construction at the Core

Respecting Foreign Judgments and $79 million for clicking “I agree”

Printed Matter, Mental Steps, and Functional Relationships: Oh My!

Patents as Holdups and the DOJ Controversy

Law of the Flag and Patent Infringement on the High Seas

Patently-O Bits and Bytes by Juvan Bonni

Microsoft, Corel, and the “Article of Manufacture”

Guest Post by Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law (Tweet @design_law)

Microsoft v. Corel, Order Regarding Post-Trial Motions (N.D. Cal. 2018)

A district judge recently issued a decision that—if affirmed by the Federal Circuit—could have major implications for design patent law and policy.

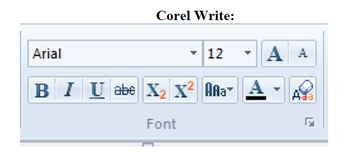

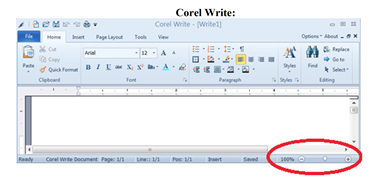

Microsoft accused Corel of infringing five utility patents and four design patents. The four design patents all claimed designs for particular elements of the Microsoft Office graphical user interface (GUI). The images below show each of the claimed designs, along with a corresponding image of an accused product (images source: Microsoft’s complaint):

|

|

|

|

|

|

Corel initially denied infringing these design patents but, early last year, it amended its answer to admit infringement and dismiss most of its defenses, stating that, “to properly develop and prove out those defenses will simply cost more than the damages could rationally be in this case.” By the time of trial, the only remaining issues were damages, whether Corel had pre-suit notice of three of the design patents, and willfulness.

In its Rule 50 motions, Corel argued that Microsoft was not entitled to recover its “total profits” under 35 U.S.C. § 289 because Corel had not applied the patented designs to any articles of manufacture.

Section 289 provides a special disgorgement remedy for certain acts of design patent infringement. (For more on what § 289 does and doesn’t cover, see FN 74 here.) It provides that:

Whoever during the term of a patent for a design, without license of the owner, (1) applies the patented design, or any colorable imitation thereof, to any article of manufacture for the purpose of sale, or (2) sells or exposes for sale any article of manufacture to which such design or colorable imitation has been applied shall be liable to the owner to the extent of his total profit, but not less than $250, recoverable in any United States district court having jurisdiction of the parties.

Nothing in this section shall prevent, lessen, or impeach any other remedy which an owner of an infringed patent has under the provisions of this title, but he shall not twice recover the profit made from the infringement.

35 U.S.C. § 289.

Corel noted that each of Microsoft’s design patents claimed an “ornamental design for a user interface for a portion of a display screen, as shown and described…” Corel argued that the relevant article of manufacture for each of the design patents was, therefore, a display screen. Sine Corel had not sold any display screens, it argued, there were no applicable profits for Microsoft to recover.

Corel also argued that its software products did not themselves constitute “articles of manufacture.”

Microsoft argued that each of its patents claimed a design “for a user interface for a portion of a display screen” and argued that, in its stipulation of infringement, Corel had “admitted that its products include[] the claimed interface.” Microsoft also argued that software does qualify as an “article of manufacture,” relying mainly on the Supreme Court’s statement in Samsung v. Apple that “[a]n article of manufacture . . . is simply a thing made by hand or machine.” Therefore, according to Microsoft, it was entitled to recover the “total profits” from Corel’s infringing software pursuant to § 289.

The district court agreed with Microsoft. According to Judge Davila, Corel waived its “article of manufacture” arguments because it “already admitted that its products. . . infringe” the design patents. Judge Davila further decided that, even if the arguments weren’t waived, “[s]oftware is a ‘thing made by hand or machine,’ and thus can be an ‘article of manufacture,” citing Samsung. The judge further stated that Corel’s arguments about the claim language were “misplaced” because the claimed design was “broad enough that it could be ‘applie[d]’ to software.”

Both of these conclusions deserve closer attention.

The admission of infringement

As noted above, Corel admitted that its software infringed Microsoft’s design patents. According to the court, this meant that “Corel has already admitted there exists an ‘article of manufacture’ to which the patented designs . . . have been applied.” It’s not entirely clear why the court reached this conclusion. But, reading the discussion as a whole, it appears that the court may have been laboring under the (unfortunately, somewhat widespread) misapprehension that § 289 sets forth the standard for design patent infringement. In other words, it appears that the court may have been under the mistaken impression that design patent infringement occurs only when the patented design is applied to an article of manufacture.

To be fair to the court, there is some dicta floating around to that effect. But, as Microsoft argued, it is § 271 that sets forth the standard for infringement of design patents – just like it does for utility patents.

In theory, someone could infringe a design patent by, for example, inducing someone else to use a patented design without themselves applying the design to any “article of manufacture” or selling an article to which the design has been applied. One reason for this is that we don’t yet have a clear conception of what it means for a design to be “applied” to an article. This decision highlights the need for more clarity in this area. (For my own views on what “applied” should mean, see here.)

The court also seems to conflate the digital instructions for rendering a design from the actual visual design itself. In copyright law, we distinguish between the code (a literary work) and the visual design displayed by the work (an audiovisual or PGS work). That distinction might be helpful in understanding the issues in these GUI design patent cases. Effectively, Judge Davila’s ruling allows for the protection of the process used to display these designs, as opposed to the designs themselves. If upheld, this could have major implications for the protection of CAD files used in 3D printing.

Software as an “article of manufacture”

The court’s alternate conclusion—that software can be an “article of manufacture”—is both surprising and, if upheld on appeal, could have far-reaching implications.

Section 171 provides for the grant of a design patent for “any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture.” There does not seem to be any good reason to interpret the phrase “article of manufacture” differently in § 289 than in § 171. (While some scholars have argued that the scope of GUI design patents should not be limited based on their verbal claims, the—admittedly scarce—case law suggests otherwise. This article collects all the relevant cases I could find as of 2015; here is another, more recent, decision.)

The question of whether a GUI design is, in fact, a “design for an article of manufacture” has never actually been decided by a court. According to the USPTO, a GUI claim “complies with the ‘article of manufacture’ requirement” if the GUI is claimed as “shown on a computer screen, monitor, other display panel, or a portion thereof.” MPEP § 1501.(a). At least in the view of the USPTO, the relevant article is the screen. Of course, this interpretation has not, however, been considered—let alone ratified—by any court. And Corel didn’t mention any of this to Judge Davila. But it’s notable how starkly the court’s reasoning in Microsoft contrasts with the USPTO’s reasoning in allowing this type of patent in the first place.

The Microsoft ruling also stands in striking contrast with Apple’s arguments in its currently-pending retrial against Samsung. Apple is arguing that the relevant article for its GUI patent is the complete Samsung phone, not the software installed thereon. It would seem odd to say that the relevant article of manufacture for a GUI is the software unless the defendant happens to sell its software bundled with a piece of hardware—especially since the Supreme Court rejected the Federal Circuit’s rule that the relevant article is whatever the defendant sells. And if it seems strange to treat Corel and Samsung differently with respect to § 289, that may suggest a deeper flaw in the reasoning the USPTO used to grant design patents for GUIs in the first place.

In any case, if the Federal Circuit affirms the decision that software can be an “article of manufacture,” that would be a major change to U.S. design patent law.

It could also have implications for utility patent law. The phrase “article of manufacture” in the design patent statutory subject matter provision has long been understood to be synonymous with the term “manufacture” in the utility patent subject matter provision. (For more on the longstanding equation of these terms, see here.) One notable exception is In re Nuijten, where the majority rather clumsily tried to distinguish a CCPA design patent case, In re Hruby, on the way to deciding that only tangible items can be “manufactures” under § 101. (Neither Corel nor Microsoft mentioned Nuijten in their “article of manufacture” briefing.)

Eventually, the Federal Circuit will need to sort all of these issues out. But this decision demonstrates how urgent the need is for clarity—and clear thinking—in this space.