by Dennis Crouch

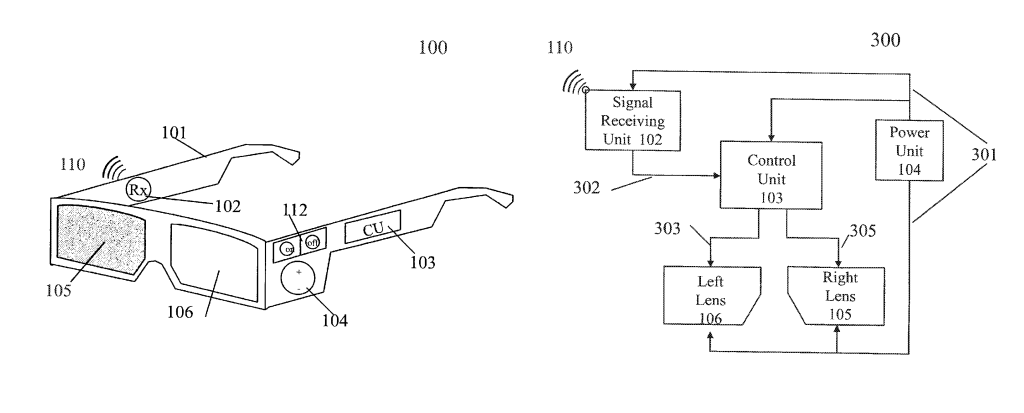

Earlier this week I was reviewing some of the USPTO's eligibility examples, noting that they were all quite old. As if on cue, the Office has released a new set of updated guidelines - focusing on Artificial Intelligence related inventions and including three new examples. In Bilski, the Supreme Court explained that the best way to understand whether a particular claimed invention is directed to an "abstract idea" is to look back on old examples for guidance. The USPTO has found that a good way to administer this approach is to provide examples of situations that pass or fail the test. Here, they introduce three new examples 47, 48, and 49. And, while the Alice/Mayo test for analyzing subject matter eligibility has not changed, the new guidance is helpful as AI technology rapidly develops. The USPTO continues to be open to issuing patents on AI inventions, including the use of AI. However, there must be a technical solution to a technical problem.

Although the guidance is effective July 17, 2024, the USPTO is open to comments via the regulations.gov portal. The agency has provided two updated flow charts for its analysis that are included below. Although the USPTO guidance is not binding law, it is the guidebook that examiners will be trained upon and required to use. As such, any patent attorney operating practicing in the AI area should dig through these examples and the particular cases chosen by the Office as representative.